Posted on 10 Jul 2023

The consequences of wildlife trafficking go beyond the threat it poses to ecological integrity and the survival of many wild species. Wildlife trafficking is also a public health threat, through its role in the emergence of zoonotic pathogens, and a national and local security threat, generating revenues for organized criminal groups and militias, and contributing to the breakdown in rule of law that exacerbates local conflict and undermines livelihoods.

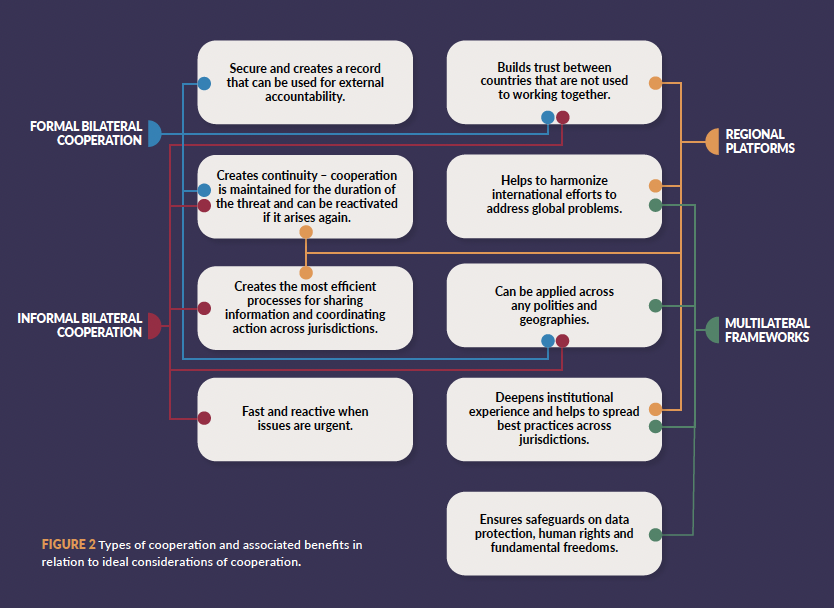

Effective transnational communication, cooperation and coordination between law enforcement and criminal justice agencies and other stakeholders along illicit commodity chains are fundamental components of a successful counter-wildlife trafficking strategy. This could include many activities, but a priority is that front-line enforcement and judicial officers have the ability to share information and intelligence with their counterparts. This could be through joint investigations and prosecutions or in the form of coordinated strategic actions to prevent the operation of wildlife trafficking networks.

Formal bilateral cooperation is hampered by the resource-intensive nature of negotiating and implementing mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs); corruption; complex bureaucratic structures with language and cultural barriers; inadequate staffing levels; and a lack of training, awareness and incentivization of staff in the implementation of the treaties.

At the multilateral level, regional platforms are regarded with a lack of enthusiasm from front-line enforcement and judicial officers, as well as NGOs. Such platforms are criticized as being expensive ‘talk shops’ with no compliance mechanisms, where member states air grievances without formulating effective responses. This can lead to varying levels of participation from member countries. Regional platforms also fail to involve all countries along illicit wildlife supply chains that are often global in nature.

At the multilateral level, the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), which incorporates a global MLAT, is having a limited impact against wildlife trafficking on the ground. There is little awareness of the existence and scope of the UNTOC within agencies focused on wildlife crimes, and the MLAT is not often recognized by national agencies. INTERPOL and the World Customs Organization (WCO) are hampered by the reluctance of enforcement agencies to use their respective systems for sharing information. These systems are perceived to be slow, inefficient, unreliable, and vulnerable to compromise, as front-line officers have multiple layers of command to go through before reaching national focal points.

NGOs play a central role in the global response to wildlife trafficking.

Government agencies are increasingly relying on NGOs to address enforcement and legislative gaps that result from the low political priority given to wildlife crime. NGOs help facilitate cooperation between states directly by assisting with information exchange, and indirectly by supporting efforts to build trust and relationships. In some cases, there are safety, security, and legal risks involved with NGOs playing this mediatory role. There is also a risk of creating a dependency on NGOs, instead of national agencies developing the required capacity and commitment to lead such roles.

In an effort to identify the current view on cooperation with an aim to developing solutions for a system that seems to be failing to address transnational wildlife crime, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) conducted research into the challenges facing international law enforcement cooperation regarding this issue.

The research set out to investigate the practical realities of international cooperation and understand why there is a disconnect between the ideal mechanisms for cooperation and what happens in practice.

This report is the result of a combination of desk research and semi-structured interviews. The desk research involved the review of academic papers, government reports, civil society research, journalistic articles, bilateral agreements and international treaties. The geographical focus of our research was Africa and Asia, as these are two regions connected by major illicit wildlife flows. The illegal trade in rhino horn, elephant and hippopotamus ivory, African pangolins, lions, animals for the exotic pet market, South African abalone and, increasingly, protected plants such as succulents show the predominantly west-to-east illicit flows from source countries in Africa to consumer markets in Asia.