Posted on 15 May 2024

Recent US sanctions aimed at deterring the kidnapping of American nationals by Islamist militants in the Sahel may send a message, but are unlikely to impact the growing kidnapping ecosystem in the region.

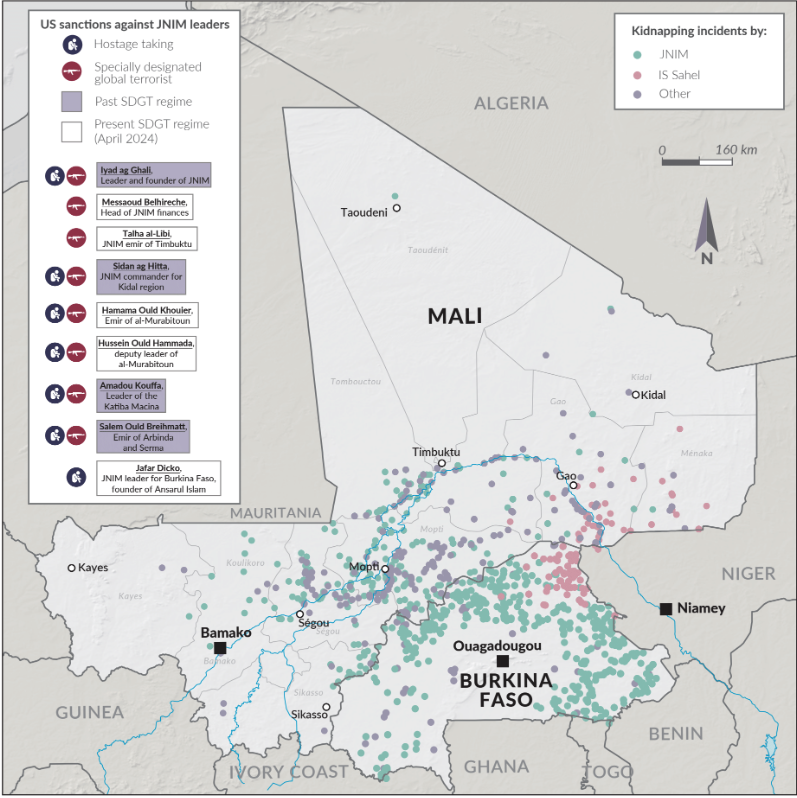

On 23 April, the United States State Department and the Treasury imposed sanctions on seven leaders of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), a violent extremist group operating in the Maghreb and West Africa. Designees include Iyad ag Ghali, JNIM’s leader, and Amadou Kouffa, the leader of the Katiba Macina, a member of the JNIM coalition, among others.

It is not the first time that JNIM and its leaders have been sanctioned. Iyad ag Ghali, for example, has been sanctioned by the UN since 2013. However, the recent designations stand out for their approach. The April sanctions are designed mainly to deter wrongful detention of American citizens, and were issued under a new sanctions regime, laid out in Executive Order 14078, ‘Bolstering Efforts To Bring Hostages and Wrongfully Detained United States Nationals Home’.

The executive order allows for the sanctioning of a host of actors, including militant groups, criminal organizations and state agents who engage in, or play a role in supporting, hostage taking of US nationals for political or financial gain. It is meant to ‘deter and … impose tangible consequences on those responsible for, or complicit in, hostage-taking or the wrongful detention of a United States national abroad.’

In practice, however, the executive order has hitherto only been used to sanction state-affiliated agencies and individuals, such as Russia’s Federal Security Service, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The designation of senior JNIM members therefore represents a shift in scope, signalling the sanction regime can also be used to target non-state actors – in this case terrorists – who engage in kidnapping and hostage taking.

It is also an acknowledgement of how JNIM has emerged as the most dominant group behind the kidnapping for ransom market across the Sahel and the wider region. The critical importance of the kidnapping market for JNIM is reflected in the individuals designated, who include JNIM leaders in charge of operations and those with core organizational roles (including the head of finance and a main negotiator for the release of foreign hostages). ‘JNIM relies on hostage-taking and wrongful detention of civilians in order to gain leverage and instill fear, creating anguish and misery for the victims and their families,’ said Brian E. Nelson, the US’s Department of the Treasury’s under-secretary for terrorism and financial intelligence.

However, while these sanctions will be seen as a high-profile move by the US to counter kidnapping, their impacts are likely to be limited, as they are out of step with the local realities of JNIM’s role in the contemporary Sahelian kidnapping ‘industry’.

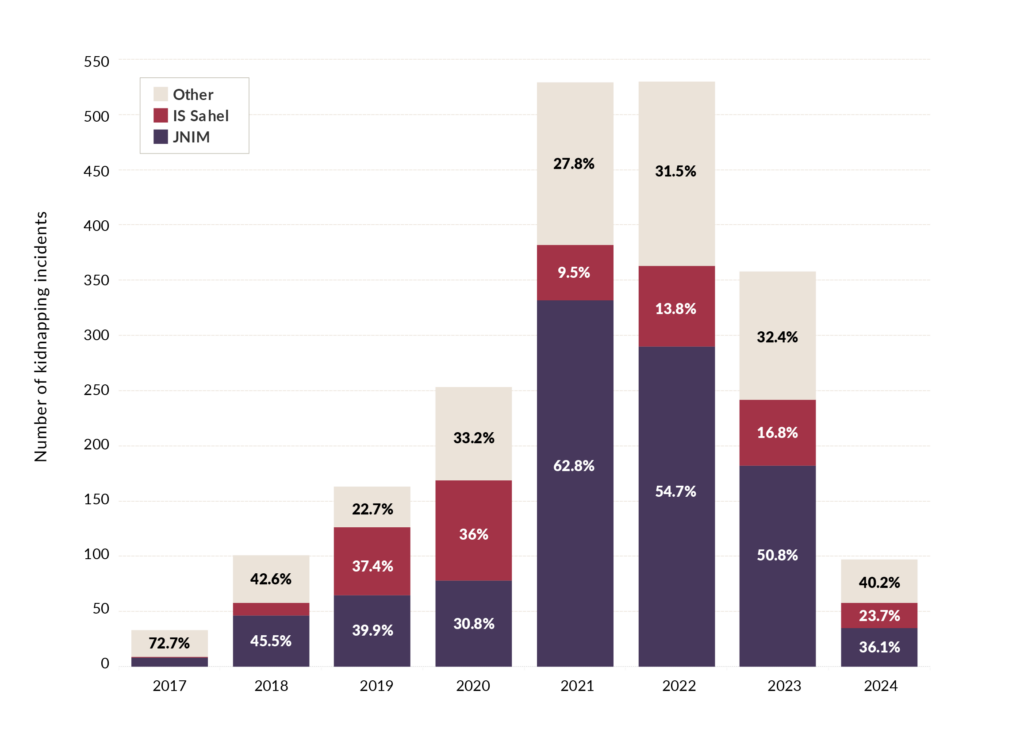

The nature of the kidnapping market has shifted since early in the first decade of the 2000s. Then, most kidnappings undertaken by armed groups in the Sahel (including JNIM’s predecessor groups) were motivated by financial gains. The kidnapping industry was a major source of revenue for armed groups at the time. It is estimated that between 2006 and 2012, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, one of JNIM’s predecessor groups, received €60 million in ransom payments. Their predominant targets were Westerners, including US nationals.

Since the middle-2010s, however, the number of foreigners kidnapped for ransom has significantly declined. This is largely due to a dwindling number of potential targets as foreigners left high-risk areas or those under the influence of violent extremist groups. Since then, there have been only a small number of sporadic incidents of foreigners being kidnapped, including the abduction of an American nun from a convent in Burkina Faso, who was released in August 2022, in exchange for an imprisoned JNIM actor. Today, foreigners constitute only a tiny proportion of kidnapping incidents and have become a less important source of financing for JNIM.

Meanwhile, kidnapping of locals has surged in the region since the late 2010s. There were more than 2 000 kidnappings recorded by ACLED between 2017 and April 2024 across Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (accounting for around 13% of all violent incidents), and Sahelian civilians were the target of over 98% of them. JNIM was identified as the perpetrator in 50% of recorded kidnappings across this period.

While hostage-taking of foreigners has drawn substantial press and policy attention outside the region, only sporadic international interest has been shown in the growing kidnapping ecosystem targeting West African nationals.

Moreover, in the current Sahelian kidnapping industry, the majority of kidnapping incidents by JNIM – which constitute a significant proportion of total incidents – do not appear to be predominantly motivated by money. Instead, kidnappings have become a key tool used as part of JNIM’s wider strategies for infiltrating and consolidating control over territories. The group appears to use kidnapping primarily for the purposes of intelligence gathering, forced recruitment, punishment and intimidation – as assessed in further detail in these reports analyzing JNIM’s use of kidnapping in Burkina Faso and in northern Benin.

The implications of kidnapping for ransom extend beyond the victims, and pose serious stability challenges. Several West African countries have been destabilized by insurgencies, which began in Mali in 2012. Our research shows that kidnapping is one of a number of ‘accelerant’ illicit markets in West Africa, alongside arms trafficking and cattle rustling. Such markets stand out for their role in fuelling instability and violence, and are enabled by conflict. Kidnapping in particular is a mechanism through which armed groups exert their control through violent governance in the central Sahel.

The April sanctions highlighting JNIM’s role in the Sahelian kidnapping industry are a significant move, in that they represent the most high-profile international action targeting kidnapping perpetrators in recent years. However, they are unlikely to have a material impact, given that most of the recently designated JNIM members are already under sanction, typically travel little beyond the region, while the group as a whole earns most of its revenue from other licit and illicit markets locally. In this sense, it is likely to prove a blunt instrument.

To effect change, a broader, coordinated regional and international response to the kidnapping industry is required, drawing together local, national, regional and international stakeholders. Any effective response – such as further sanctions, law enforcement coordination, targeted aid support and strengthening the part played by civil society in vulnerable communities – needs to be tailored to the kidnapping challenge faced first and foremost by West Africans, and not just Westerners.

Responses that focus only on kidnapping threats faced by Westerners are unlikely to gain any traction within the Sahel and West Africa, and are doomed to miss the mark. A more meaningful way to mitigate risks of Western hostage taking in the region is to comprehensively address the far broader and more acute threat posed by the kidnapping ecosystem preying upon locals.