Posted on 26 Oct 2022

The UN Security Council has created a UN sanctions committee targeting criminal gangs in response to extreme levels of gang violence in Haiti amid a political vacuum and a humanitarian crisis. This marks a departure for the Council, in that it is the first time the council has made criminal groups the main focus of sanctions, recognizing their role in undermining peace and security.

On 17 October, the UN Security Council met on the security situation in Haiti. They heard alarming reports of widespread violence against civilians, rape and gender-based violence are being deployed as a pervasive weapon against civilians, acute hunger to the point of starvation, a growing cholera epidemic, and gang-induced shortages of basic needs like water and fuel. Gangs have been the main perpetrators of this violence, and are instrumental in the country’s humanitarian and economic disruptions.

The Council heard that although routes to address the ongoing political impasse – spearheaded by political parties and sectors of society such as academia, religious groups and the private sector – have been pursued, they have stalled and the political process is not advancing. Large-scale protests have mounted since the September decision to remove fuel subsidies and increase taxes, and these have spilled over into looting of businesses and UN agencies, such as the World Food Programme.

In this context, the Secretary-General consulted the Haitian government, a small group of countries and regional organizations on possible options for enhanced security support, and provided the Council with options to consider. Meanwhile, the current administration of Ariel Henry has also called for foreign military assistance to address the issues.

When the Council met on 17 October, the United States and Mexico (the penholders on Haiti) were together drafting two resolutions for members to consider. The first would create a new sanctions regime targeted at the criminal gangs and their financiers, as well as arms supplies. The second would approve, under Chapter 7 of the UN charter, a non-UN international security operation to counter gangs. While both responses are staple Council measures, they are unique in this context. The proposal of a UN sanctioned non-UN security force is atypical, as is the use of either of these measures to target domestic gangs. During the debate, there was far more willingness among Council members for creating a sanctions regime than a military intervention. On 21 October, the Council reconvened and unanimously approved a reworked resolution for a sanctions regime, while the second resolution has been shelved for now.

A potential military intervention during a time of gang violence and popular protest raises some key concerns. The first is the risk of erroneously targeting civilians engaged in protest, which could happen because of lack of local knowledge. Second, introducing more weapons and armed actors into the situation may have knock-on effects, such as giving gangs more combat experience or helping unify them against a common foe. There is also a deep lack of trust among Haitians given UN peacekeepers’ past involvement in sexual violence and the outbreak of cholera in 2010. While a short-term military intervention could help alleviate some elements of the current situation, it would also reshape power dynamics of gangs in ways not fully realized. Without promising long-term political or economic solutions, the potential short-term repercussions are therefore risky.

A new sanctions regime takes shape

The UN has sanctioned criminal actors in the past. However, the new Haiti regime stands out due to its explicit focus on criminal actors within the regime’s designation criteria. The new sanctions regime for Haiti (Resolution 2653) establishes an asset freeze and travel ban for listed individuals and creates a targeted arms embargo where states are compelled to stop the direct and indirect supply of weapons to designated individuals and groups.

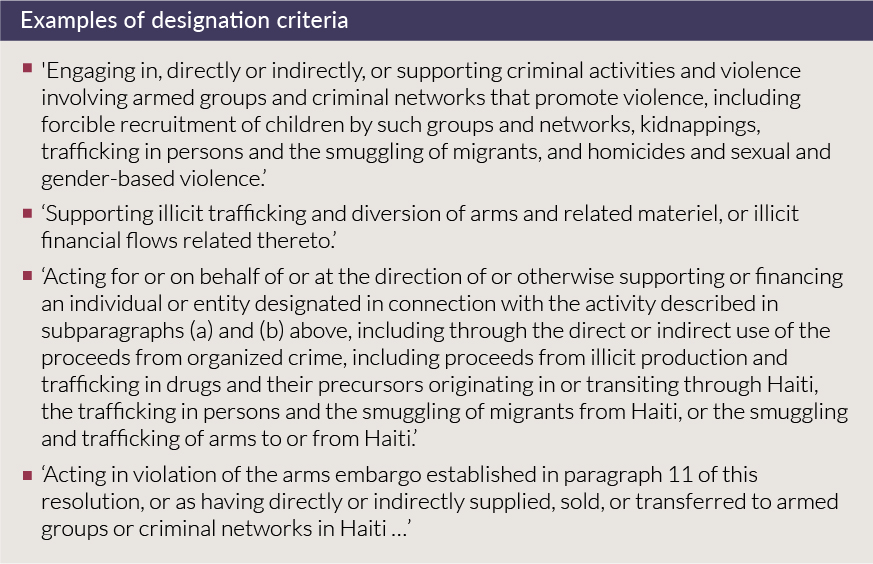

The listing criteria (see below) include both involvement in criminal groups and networks who threaten peace and security or promote violence, and engaging in illegal trafficking that supports the group, referencing arms, drugs, and human trafficking and human smuggling specifically. Listing criteria include perpetrating sexual and gender-based violence, human rights violations, obstruction of humanitarian assistance and attacks on UN personnel or premises. The Sanctions Committee has sanctioned its first designee, Jimmy Cherizier, a former police officer and leader of the G9 gang coalition. Cherizier is known to be responsible for mass violence and economic blockades that have led to fuel shortages.

During the meeting approving the regime, Council members echoed that this step will send a strong message to gangs in Haiti while underscoring that the Council is willing to respond at this critical time to assist a country long accustomed to international interventions. But its efficacy as a tool against largely domestic actors and illegal financial channels will be put to the test in implementation.

Many gang leaders and actors have a local sphere of influence. Cherizier, for example, has been previously sanctioned by the US in December 2020 for human rights violations, and there is little reason to believe that sanctioning him again will encourage him to change. Many other gangs make money from kidnapping and extorting local community members, so their revenue is locally sourced and circulated. Sanctions are more likely to impact high-level political and business financiers of gangs. Exposing and designating such individuals will require the political will of and bargaining among Council members. While addressing the acute issues of the moment, the regime does not include corruption or the ability to freeze assets taken from government coffers – a key concern of Haitian civil society. In this respect, it does not link to the UN Office in Haiti’s mandate under justice reform.

Reducing the numbers of weapons flowing into Haiti could significantly help curtail levels of violence. While weapons are moved largely by means of smuggling networks, there are entry points that deserve more attention, and with a new directive, states should be encouraged to make it a priority. In response to the kidnapping of US and Canadian missionaries in October 2021, the US arrested three men in Florida who had purchased hand guns, rifles, pistols and ammunition in Florida at the request of the 400 Mawozo gang and sent them to Haiti in shipping containers. This case, along with other examples, shows that focusing on the pipeline of weapons into Haiti would be a tangible and significant response.

If the new sanctions regime can be used to dry up finances and weapons for gangs, it could have some impact. To do this, it has to expand beyond the gang leaders and focus on the money and weapons. There will be knock-on effects that require attention: for instance if foreign financing dries up and gang power persists, will kidnappings increase? The listing of high-profile economic and political actors could send a signal to others of real repercussions for supporting gangs. These new sanctions are one part of a response that needs to focus on long-term security, and political and economic solutions at the same time.