Posted on 27 Jan 2022

Scheduled January debates on a global cybercrime treaty have been postponed in the wake of the Omicron wave. Despite Russia’s push to hold the meetings as soon as possible, the country has once again lost out through votes on its preferences, suggesting that the process it initiated is slipping further away from its control.

The negotiations for a new cybercrime treaty were scheduled to take place on 17 January 2022 at the UN’s headquarters in New York, which bears significance for a number of countries that do not have diplomatic missions in Vienna. The first ad hoc committee meeting was supposed to begin debate on the scope, structure and key elements of a potential instrument to counter cybercrime. Governments were also meant to address a final list of representatives from outside the UN to participate, including members of civil society, and establish the working methods for the process moving forward.

However, the UN changed all January meetings in New York to virtual formats because of concerns over a spike in COVID-19 cases derived from the highly contagious Omicron variant. This meant voting could not happen, which would be needed in case consensus could not be reached on the issues under discussion. Hosted by the chair of the ad hoc committee, informal meetings to find a solution to this had been ongoing among diplomats in Vienna up until 14 January, and a number of alternative options were suggested – such as relocating the first meeting to a hybrid format run out of Vienna or holding all proceedings virtually – but no consensus was reached.

As the ad hoc committee negotiated informally, Russia submitted a resolution for a vote at the General Assembly. Its draft resolution proposed holding the meeting in New York only one week later, on 24 January, in defiance of the secretariat’s directive on the impossibility of holding meetings in that time frame and the scepticism of other member states. As occurred in May 2021, this escalated the issue towards a rapid conclusion rather than arriving at a compromise, which may have been reached had informal consultations continued.

The Dominican Republic, with predominantly European and Central American co-sponsors plus Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the United States, submitted an amendment to Russia’s resolution calling for a one-day organizational meeting no later than the end of February and the full negotiating session in New York no later than 18 April, unless that arrangement were to be unfeasible due to pandemic restrictions, in which case the meeting would be held in Vienna in May. This was followed by a further proposed revision by Belarus, a close ally of Russia, which agreed to the meeting in New York no later than 18 April, but which discarded the rest of the items in the Dominican Republic’s amendment.

The resolution and proposed revisions were brought to a vote in the General Assembly on 20 January, where the Belarussian amendment was voted down and the Dominican Republic’s amendment passed. With that, Russia’s resolution, amended with all the proposed revisions by the Dominican Republic, was approved by vote. After the revisions were in place, Russia voted against its own resolution, making it known afterwards and asking for a tabulation of the votes for its records.

Russia was clear that it regarded the position of the secretariat as unreasonable, claiming that many other meetings were taking place at the UN in New York. Those who favoured the Dominican Republic’s amendment were supportive of the chair’s leadership of the ad hoc committee process and efforts to find consensus, and critical of Russia’s insistence on pushing the meeting ahead despite the logistical and health concerns.

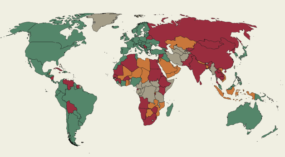

This is the second time in a year that Russia, who launched the cybercrime initiative through the General Assembly in 2019, has tried to force the hand of other governments by taking procedural decisions to a vote in the General Assembly – and lost. While Russia clearly sees itself as the leader of this initiative, its attempts to push through its preferences are being met with significant – and successful – resistance from a large group of countries.

With negotiations requiring a two-thirds majority on issues taken to a vote and repeated resistance to Russia’s efforts to drive the process, the polarized and political nature of this discussion rages on. And those countries who were originally not in favour of a new convention, or who did not have a strong position on it, seem to be wresting control of the process from those who started it and most want a new convention. This political manoeuvring shows once again that the foundation of these negotiations is rooted in anything but agreement, a fundamental challenge when building an instrument for international cooperation around a complex transnational form of crime.