Posted on 02 Jun 2021

On 26 May 2021, a resolution on cybercrime was voted through the United Nations General Assembly. This resolution was mainly organizational, determining the rules and process to debate and possibly draft a treaty ‘on countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes’, but was subject to strong disagreement among member states, with serious doubt as to whether progress was possible.

The General Assembly took place in the wake of two major cyber incidents, providing timely evidence of the need for a response. On 7 May a ransomware attack by the cybercrime group DarkSide on Colonial Pipeline forced the company to shut down its pipeline, leading to panic buying at petrol stations across the US eastern seaboard, until Colonial Pipeline made a US$4.4 million ransom payment to the group to restore operations. A week later, Ireland’s Department of Health was hit by a ransomware attack that caused widespread cancellations of medical appointments.

Within the UN rooms, the debate over the rules and process was often fractious. A previous meeting on 10–12 May 2021 intended to establish these rules came to an acrimonious halt, before intense negotiations between diplomats and interventions from several member states at the General Assembly helped break the deadlock. After Russia advanced a still-contested resolution to the General Assembly floor for a vote on 26 May, efforts led by Brazil, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries and the United Kingdom led to the passage of three amendments which could result in a more inclusive process beginning in 2022. At the same time, stark disagreements have revealed themselves long before states have even begun to discuss substance, suggesting a complicated path ahead for this agenda.

The first May meeting

The 10–12 May organizational meeting was meant to appoint the committee members and agree on a resolution which defined the modalities for the committee’s upcoming work. The members of the ad hoc committee were appointed during the meeting and immediately assumed their roles, but beyond that, not much else was decided.

At the onset, two resolutions were submitted – one by the United States and one by Russia – outlining different visions of how the committee would operate. The Russian proposal wanted the process run out of New York through the General Assembly, primarily in order to make sure decisions could be taken by majoritarian vote rather than consensus. The process towards a cybercrime treaty was originally initiated by Russia and approved by vote in the General Assembly (79 votes to 60, with 33 abstentions), and Russia thinks it can best lead and direct the agenda in this context. However, Western and Latin American states, many of which voted against this agenda back in 2019, heavily support a consensus-based process running out of Vienna, where previous cybercrime debates have been held through the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ).

Some states against a vote-based process noted that a majoritarian-based (50+1) convention is unlikely to be signed onto by those opposed and so would not have practical relevance. However, it is possible Russia is not looking for a big tent agenda, but rather leadership among future signatories, perhaps as an alternative to the Council of Europe’s Budapest Convention on cybercrime. During the meeting, Russia noted that the goal of the convention is to ‘bridge the technological gap between developed and developing countries’. It is possible Russia sees the process as a way of leading such technical cooperation. Interestingly, China, a key country in cyber issues, provided quiet support to the Russian position, but was not very vocal during the first meeting.

There are other aspects to the debate over Vienna or New York. For instance, the argument for New York-based negotiations included the key point that all member states are present, unlike in Vienna, while those in favour of Vienna argued that the UNODC (which will manage the process) and the bodies that negotiate crime-related issues are based in Vienna. But ultimately, the New York–Vienna debate was about how decisions would be made.

On the last day, and with roughly one hour left of the entire meeting, a compromise text was submitted by Russia and the US. (Other states said they were drafting compromise texts, but none of these were discussed in the main meeting.) As the chair began the review process, it became clear that the compromise was skewed heavily in Russia’s favour on key issues, apart from holding meetings in Vienna (a key US and EU objective). While Russia agreed to hold meetings in Vienna, they would be under General Assembly rules, including the 50+1 vote.

Russia suggested that the new resolution be adopted as is, whereas Western and Latin American states were concerned that their suggestions were not being taken into account. The CARICOM countries, for example, wanted more meetings held in New York because they lack representation in Vienna. A number of countries requested a compromise of a 2/3 voting structure given the impasse on consensus versus voting. Access for civil society was also a contentious point. The United Kingdom and Switzerland, among others, raised concerns that the language on multistakeholder involvement, including civil society, was not in line with recent General Assembly decisions and not inclusive enough.

The chair referred to the resolution – which many remained unhappy with – as a ‘fragile consensus’. While the chair updated some language in the text, she ignored other suggestions, leading the UK to ask why she was ‘cherry picking’ language to include as compromise text.

There was a clear division between states who had been part of earlier negotiations and those who had not, and the chair’s insistence that these discussions had been going on for six months did not sit well with governments who felt unrepresented. She offered to footnote everyone’s concerns (meaning they do not become guiding rules for the process) and take the resolution to a vote, saying she knew she had the votes to support it. The UK objected heavily to this, asking why the chair was able to presuppose she had the votes for passage, and threatened to leave the overall negotiations if things carried on in this way.

The second meeting: the rush to vote

After the microphones cut off and the meeting ended abruptly on 12 May, it appeared that states would move into informal meetings to finalize the text and send a resolution for approval. However, on 24 May Russia submitted the existing compromise resolution to the General Assembly for a vote on 26 May. This abruptly stopped the ad hoc committee’s arrangements for informal meetings and led many member states to note the irony of a rushed and divisive vote on how decisions should be taken.

In addition to the resolution, three amendments were submitted by member states to be voted on at the 26 May meeting:

- Brazil represented the countries wanting to amend the Russian resolution by including the 2/3 voting structure, rather than the simple majority favoured by the Russians.

- Haiti introduced an amendment on behalf of CARICOM to balance the meetings between Vienna and New York (three meetings in each location).

- The UK introduced an amendment to decrease the ability of member states to block external participants (including civil society) by ensuring that any objection must be agreed by the ad hoc committee.

In the debate before the vote, Russia and China lobbied for the adoption of the Russian text and the rejection of all three amendments. The US had removed its name as a co-sponsor of the resolution. The delegate said that the US would not vote for the resolution in this rushed manner and the vote suggested ‘narrow divisive voting’ would be the norm in the process. EU member states, the UK, Norway, Australia, Switzerland and others said they would not vote in favour of the current resolution under these circumstances. The delegate from Kiribati, the last speaker before the vote, perhaps summed up the mood best when he said the membership seemed to be growing farther apart and needed more time.

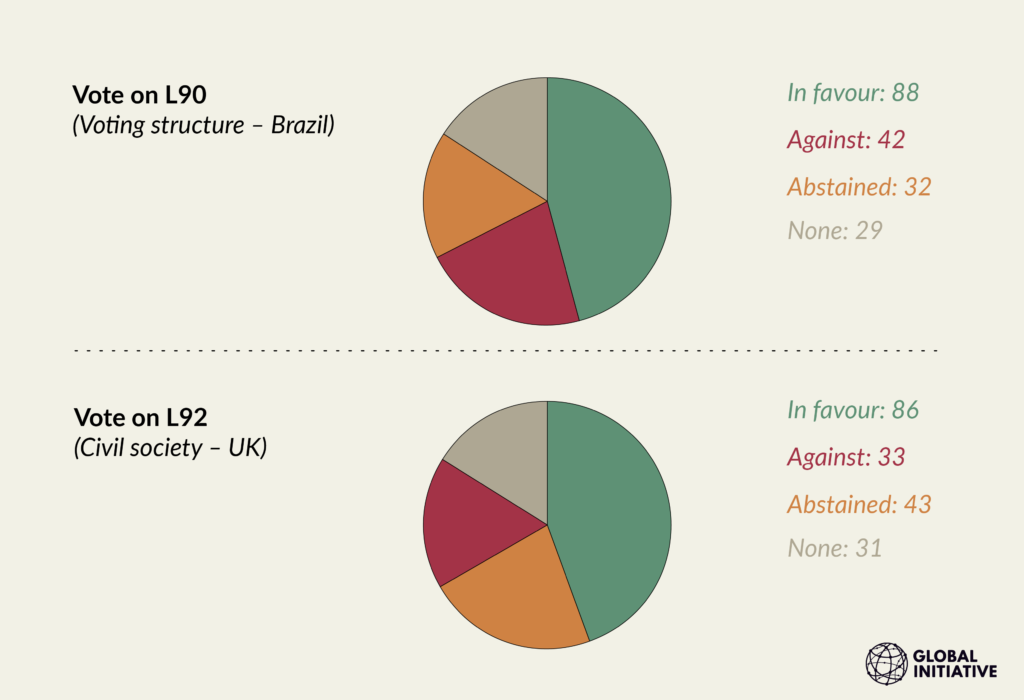

So it was perhaps surprising that all three amendments were in fact approved by large margins. The CARICOM amendment was accepted without being brought to a vote, signifying general acceptance. The other two amendments were approved by recorded vote. With the amendments approved and incorporated, the Russian resolution was then adopted without a vote, again showing a general acceptance to move forward. The results showed some predictable cooperation, but also raised some questions of what types of alliances will come to shape the substantive debates beginning in 2022.

Click here to view the vote in details

What the vote reveals

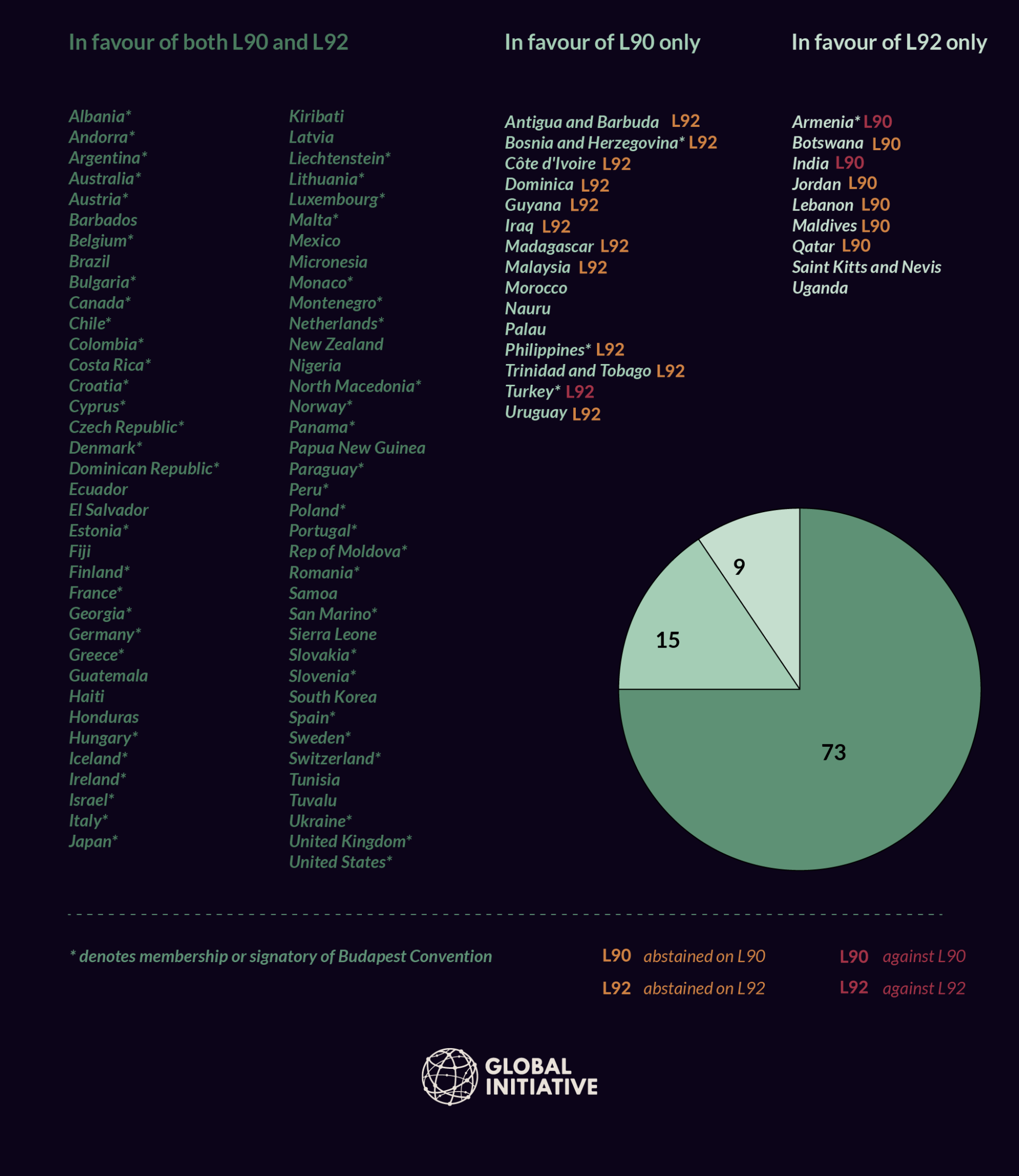

Brazil’s amendment was voted on first, with 88 in support, 42 against and 32 abstentions. It was largely carried by Latin American, European and Pacific island member states, as well as the US, Japan and Nigeria, among others. The UK amendment was also approved largely due to support by the same group, with a higher number of abstentions. The UN voting blocs Group of Latin America and Caribbean Countries (GRULAC) and Western European and Other Group (WEOG) often align on crime debates at the UN, and the shared dissatisfaction from countries in these groups was evident during both meetings.

The other clear voting group consisted of those that voted in line with Russia against both the UK and Brazil amendments. This group was geographically spread but largely strategically aligned, including China, Cuba, Egypt, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Zimbabwe. Many of these countries often align in other areas as well, such as drug policy.

As expected alliances revealed themselves, it is clear that there is a third group who will be eagerly sought after by each camp. Ambivalent voters and countries seeming to buck the trend of their larger coalition will be states to watch as the horse-trading on substance begins, such as Jamaica which joined the ‘no amendment’ group. Some members of the Council of Europe’s Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest Convention) – Mauritius, Senegal, Serbia and Sri Lanka – also voted with this group on one or both amendments. CARICOM countries split votes on the two other amendments, signifying they did not agree to vote as a bloc once their amendment was safe. Much of the Arab world and many African countries abstained on both votes. Some countries voted for one amendment and not the other. Many of the countries in this group are likely interested in how this convention could deliver technical assistance, and balancing interests between legal and technical cooperation will arise in future negotiations.

States will now have until 2022 to regroup and consider what their objectives are for this process. Cybercrime is likely to change drastically in that time, and states’ priorities in this space are likely to shift too. But the truth remains that this should have been the easy part – formulating an effective treaty against cybercrime will be far more difficult, as many divergent interests compete to rise to the top.