Posted on 11 May 2023

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted thousands of Russians to flee their country for fear of political persecution. Migration flows from Central Asia, particularly Uzbekistan, have also surged. Many seek refuge in the US, facilitated by Russian- and Uzbek-speaking smuggling networks operating in Turkey, Central America and Mexico.

On 11 May 2023, a US health policy known as Title 42 – which allowed authorities to turn back migrants at the border as part of measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 – will be lifted as the current administration ends the COVID public health emergency. This is likely to drive an increase in irregular migration through the country’s already overwhelmed south-west border. Despite restrictions on crossing the border, the flow of undocumented migrants to the US reached record levels in 2022, and nationalities seeking to reach the US became more diversified.

According to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data, there were over 2.3 million encounters with irregular migrants at the southern border in 2022. Although Russian nationals constituted just 1 per cent of these, their numbers represented a fourfold increase compared to the year preceding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As of March 2023, Russian nationals had reached a record high, accounting for 30 500 migrant encounters, a dramatic increase from 467 in 2020. Given the current political context in Russia, the share of its nationals among migrants is likely to continue rising, fuelled by asylum seekers who flee political persecution at home.

Migration flows from Central Asia, particularly Uzbekistan, have also increased in recent years. In 2021, the CBP’s Yuma Sector border area in south-west Arizona registered an uptick in irregular crossings of Uzbekistan nationals. Uzbek authorities have reported arrests of people in Uzbekistan who offer illegal avenues for migrants to reach the US via Mexico.

Ongoing research by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) on these dynamics shows that the increased demand for smuggling services has created favourable conditions for a range of criminal activities associated with migrant smuggling. With such a large exodus from Russia, smuggling networks have adapted to absorb the new clientele. Dedicated channels on messaging platform Telegram have become the primary means of communication for those planning the journey, those en route and those who have successfully crossed the US border. A never-ending exchange of experiences through a vast network of Telegram channels allows migrants to avoid airline scrutiny, find fellow travellers and hire facilitators in Mexico. These channels are public: they can be found and accessed by any Telegram user through a search function by key words entered (e.g., ‘Mexico’, ‘immigration’, ‘Nicaragua’ or ‘Tapachula’) in Russian.

Transiting Central America and Mexico

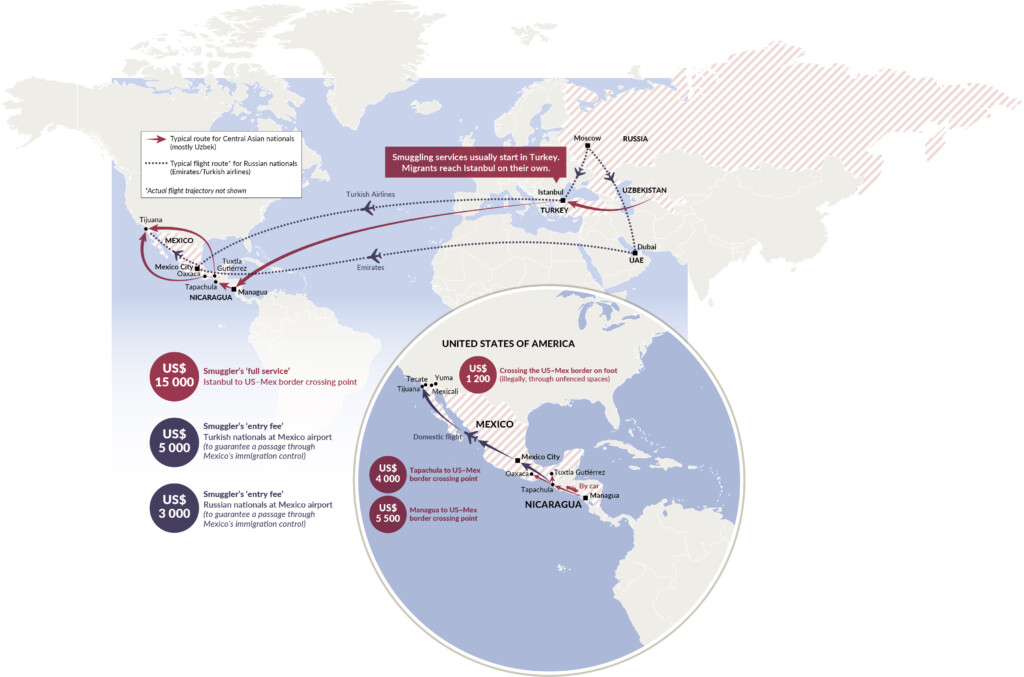

The routes taken by Russian-speaking migrants to reach the US–Mexico border partly depend on their citizenship. Obtaining a tourist visa for Mexico is significantly easier for Russian nationals than for those of Central Asian countries. Russians typically travel by air from Istanbul or Dubai to Mexico City. They then take a domestic flight to Tijuana, on the border with California.

For Central Asian migrants, the journey is more treacherous. Since obtaining a Mexican tourist visa is logistically difficult, they usually travel to Central America (mainly Nicaragua and, to a lesser degree, Panama) and proceed to Mexico by land or boat through widely used migratory routes.

Data gathered by the GI-TOC shows that the journey for Central Asian nationals begins in Turkey, where some members of the smuggling ring are based (Uzbek and Turkish belong to the same language family). Upon their arrival in Nicaragua, migrants are picked up by local ‘coyotes’ who lead them in groups to Tapachula, a city on Mexico’s southern border. Alternatively, a local accomplice may pick them up in Nicaragua by car and drive them to Tapachula.

From southern Mexico, migrants take a domestic flight to Tijuana, where an Uzbek-speaking smuggler receives them. Tijuana-based smugglers, some of whom are known to speak Uzbek, guides their clients by telephone throughout the entire journey from Turkey and often accompany them to the US side of the border. The service for the full route costs between US$15 000 and US$24 ,000; the leg of the journey from Tapachula to Tijuana costs US$4 000.

Crossing into the US

When attempting to pass a screening procedure at an entry point on the south-west border, asylum seekers must submit their information in advance and schedule an appointment through the mobile app CBP One, introduced in January 2023. The app has been plagued with glitches and provides few time slots, which prompted the US Congress to call for greater equity in its accessibility.

Meanwhile, on Russian-language channels on Telegram users share tips on how to best secure an appointment through CBP One. It is not uncommon for families to stay in Mexico for over a month while waiting for their appointment. Many opt to cross the border illegally to avoid the long wait.

However, on 3 May 2023, administrators of a popular Russian-speaking Telegram channel dedicated to the CBP One app began advertising new software designed to overcome the app’s shortcomings and delays. The software reportedly allows users to schedule an appointment in minutes. Channel administrators offer this service for US$15. Telegram chats quickly became breeding ground for scammers, who offered assistance in scheduling appointments and disappeared after receiving the payment.

Russian-speaking smugglers offer services to cross the border on foot (at a fee that ranges from US$750 to US$1 200) to those stuck in border towns. This leg of the journey typically starts in Tijuana, where migrants are picked up by car by Mexican coyotes who work in conjunction with Russian- or Uzbek-speaking smugglers. According to advertisements by an Uzbek-speaking smuggler, migrants are driven to border areas around Mexicali or Tecate, where they are placed in safe houses until dark. They are picked up by a coyote around 10–11 pm and taken across the border in groups to turn themselves in to the US authorities to seek asylum. This path seems to be the least preferred by Russian nationals because of its potential dangers.

Russians are perceived as wealthier than other migrants, potentially making them targets for robbery by local criminal groups. Compared to those fleeing poverty in Latin America, Russian asylum seekers tend to stay in hotels or rent apartments, travel to border towns by plane and have more sophisticated mobile phones. Although a review of Telegram communications indicates that Russians have been victims of theft and fraud while in transit in Mexico, they have mostly been spared the typical dangers of the journey. Cases of kidnapping and attempted extortion among Russian-speaking migrants, nevertheless, have been reported, although they seem infrequent.

Coexisting with established players

Russian-speaking smuggling networks are highly agile, with members linked by linguistic and cultural ties, and spanning several continents. Facilitators in Mexico who speak Russian exploit their knowledge of the local context and contacts with coyotes to attract new clients. However, they do not act in a vacuum. Mexican drug cartels are also significant players in the migrant smuggling business, either organizing smuggling operations themselves or charging a passage fee from independent coyotes. These migrant flows occur within established border crossing networks, as Russian-speaking facilitators buy services from Mexican coyotes as opposed to conducting independent smuggling operations.

How the end of COVID-19 restrictions on foot crossings into the US will affect the dynamics of migrant flows remains to be seen. However, the influx of Russian-speaking migrants, and of many other nationalities who had been turned away under the Title 42 provisions, is likely to stimulate criminal markets at the US–Mexico border.