Posted on 29 Jun 2017

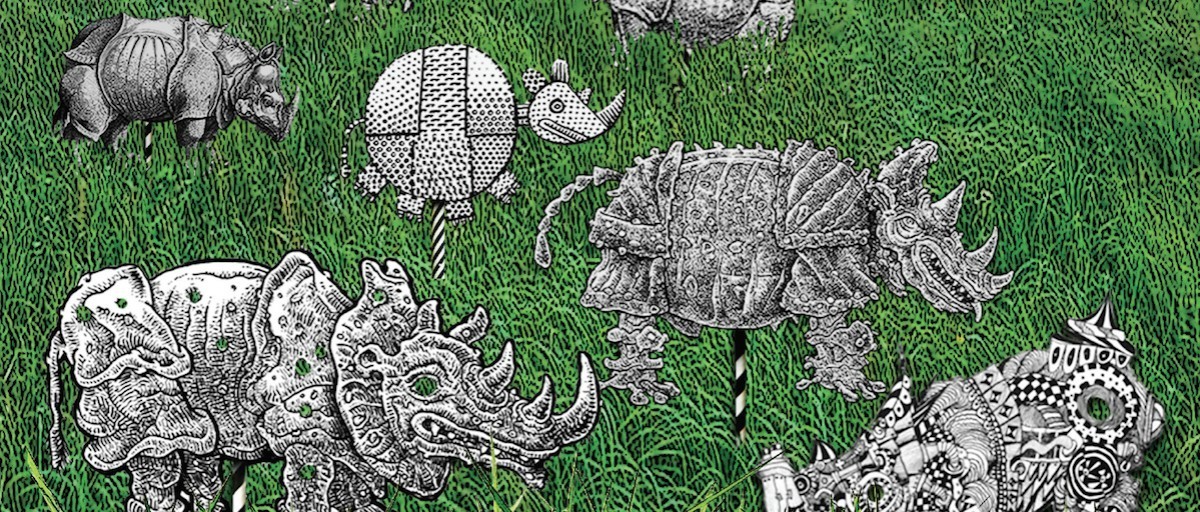

South African Crime Quarterly (SACQ) Vol. 60: Special Edition on Organised Environmental Crime

Once considered peripheral, and a green matter, wildlife crimes have moved up global security and policy agendas. The UN General Assembly, for example, adopted two resolutions to tackle wildlife crimes in 2015 and 2016. Meanwhile, South Africa and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have declared wildlife trafficking a priority crime issue. Rhino poaching, in particular, has captured the attention of the public, the international community, and our national government. Less charismatic plant and wildlife species are also harvested and trafficked across the globe. The lesser-known pangolin is considered the most trafficked species while cycads are the most threatened plant species on the planet. The illegal or irregular extraction of natural resources, logging, mining, overfishing, trafficking of toxic, nuclear or electronic waste, and industrial dumping have all become areas of concern.

A plethora of protective and regulatory national and international measures have failed to disrupt the consumer markets and criminal networks that allow these trades to flourish. While conservation is often regarded as a pastime of economic elites, the impact of environmental degradation disproportionately affects poor people. The role of local people in the protection and management of natural resources has become a policy prerogative in many southern African countries. However, good intentions and long-term goals are often uprooted in the pursuit of short-term concrete outcomes that supposedly bring down poaching statistics. Shrouded in the terminology of a ‘war on poaching’, securocrats have called for more helicopter gunships and boots on the ground, while sustained community empowerment and coordinated transnational law enforcement responses seem to have taken a backseat. In the current environment, the perception that wild animals are valued more highly than black rural lives is difficult to dismiss.

South Africa, meanwhile, remains the most unequal country in the world. We know that inequality predicts all sorts of societal ills, most notably crime. Thus, it is not a coincidence that South Africa is both notoriously unequal and crime saturated. Income inequality also produces opportunity inequality. On 1 June 2017, Statistics South Africa reported that the country’s unemployment rate of 27,7 percent was its worst in thirteen years. That same day, the publication of over a terabyte of leaked emails between the Gupta brothers (a business family controversially close to President Zuma) and various business people and government ministers, hinted at billions of rands in kickbacks and dodgy deals, enriching a tiny group of politicians and business people.

South Africa is home to some of the world’s largest and most diverse populations of endangered flora, fauna, and mineral resources. Structural inequality is also reflected in terms of who benefits from conservation in general, protected areas and profits associated with the sustainable use of natural resources. Economic and political elites continue to reap the benefits while local people are often excluded or marginalized. It is perhaps not surprising that some people who have been denied sustainable livelihood strategies in the face of endemic corruption and abundant opportunity might be tempted by the promise of high returns and low risk to get there. Rhino horn, for example, has a street value higher than that of heroin or cocaine in consumer markets. The profits of a single rhino horn trump the annual income of many rural residents in South Africa, some of whom organised crime networks try to recruit as poachers.

The real perpetrators are organised crime networks, corrupt government officials and members of the wildlife and conservation industries who facilitate the flow of illicit wildlife and plant contraband. Law enforcement officials and policy-makers have been focusing their efforts on reigning in poachers rather than buyers and intermediaries. The latter organise and coordinate the transfer of wildlife contraband and other natural resources from the bush to the market. These actors are usually well connected and able to access transnational trade networks. Progressive scholars have started to look at the root causes of environmental and wildlife crimes by considering broader economic, political and systemic factors. Their assessment is that broad-based community empowerment is key, not only to addressing structural inequality and poverty but to alleviating wildlife crime and other crime types. Is the fight against organised environmental crime more important than the dismantling of organised structural inequality and poverty? Or do we need to take cognisance that responses to these societal ills are perhaps interlinked? Local communities may, for example, become protectors of wildlife and conservation areas if they were granted agency, ownership and beneficiation.

In June 2016, when the University of Cape Town put out a call for papers for this special issue, which is funded by the Global Initiative, what was striking about the many abstracts received – and what remains true of the contributions to this issue – was the narrowness with which many of the authors approached the subject, despite the diversity of environmental crimes and responses taking place.

Perhaps not surprising in the broader political context of South Africa in 2017, white South Africans and researchers from Western backgrounds and institutions were over-represented. In the call, we had pointed to the gaps in the scholarly and policy literatures. However, most authors chose to focus on the poaching of charismatic megafauna and law enforcement responses to wildlife crime.

We accommodate in this issue a plethora of views and policy suggestions, which are by no means an endorsement of such. Many readers will find the proposal of ‘shoot-to-kill’ as a serious anti-poaching strategy difficult to accept from a human rights perspective, as will the suggestion that rhino poaching should be seen as a form of cultural victimisation. However, such views are best debated and it is in this spirit that the Global Initiative was pleased to fund the journal as open access and to make these articles available to an audience of policy makers, practitioners, and scholars to debate more widely.

Table of contents – SACQ 60

Editorial: Organised environmental crimes: trends, theory, impact, and responses

Annette Hübschle and Andrew Faull

Research articles

- Society and the rhino: A whole-of-society approach to wildlife crime in South Africa

Duarte Gonçalves - Inclusive anti-poaching? Exploring the potential and challenges of community-based anti-poaching

Francis Massé, Alan Gardiner, Rodgers Lubilo and Martha Ntlhaele Themba - Poachers and pirates: Improving coordination of the global response to wildlife crime

Olga Biegus and Christian Bueger - Responding to organised environmental crimes: Collaborative approaches and capacity building

Rob White and Grant Pink

Commentary and analysis

- Heritage lost: The cultural impact of wildlife crime in South Africa

Megan Griffiths - Live by the gun, die by the gun: Botswana’s ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy as an anti-poaching strategy

Goemeone EJ Mogomotsi and Patricia Ke lwe Madigele

On the record

Interview with Major General Johan Jooste, South African National Parks Head of Special Projects

Annette Hübschle

The volume was edited by Annette Hübschle, a member of the GI Network of Experts, who has been on a GI-funded Post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Cape Town since 2016, and is leading the development of the Environmental Security Observatory, a joint initiative between the Global Initiative and UCT.