Despite signing a number of commitments to counter human trafficking and forced labour, governments in Gulf states are falling short in the fight against the most pervasive form of criminality in the region.

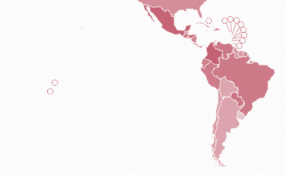

A key theme cuts across the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s Global Organized Crime Index 2021 among the six states that make up the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Index finds that the most pervasive criminal market is human trafficking. Four of these countries score at least 8 out of 10 for this indicator in the Index, meaning that human trafficking has ‘a negative influence on nearly all parts of society; it is highly profitable, and the market accrues significant value’. Few regions in the world score as poorly as the Gulf for this indicator.

These scores are a reflection of the human suffering that exists on a significant scale in the region. The Gulf states are highly dependent on low-paid migrant workers, predominantly from Asia and increasingly from Africa. Around 30 million foreign nationals – more than half of the region’s total population – sustain a wide range of economic sectors from domestic work to hospitality and construction. Subjected to repressive Kafala employment systems – which define the relationship between foreign workers and a local sponsor, or kafeel – tied to their employers and denied rights to unionize, foreign workers face a catalogue of abuses, including having their passports confiscated, wage theft and physical violence. Such abuses, which often amount to forced labour, have been widely documented in recent years in the lead-up to Qatar’s 2022 World Cup, which became an emblematic eye-opener for practices that prevail in the Gulf region.

Human trafficking is rife, with workers routinely lied to about exploitative terms and conditions during the recruitment process and made to pay extortionate fees to secure their jobs. These payments may take place in origin states, but the financial benefit is often enjoyed by employers in the Gulf who get discounted recruitment at the expense of the worker. When foreign workers reach the end of their contract, some employers monetize their control over them by selling them to other employers. A 2019 BBC investigation found that women domestic workers in Kuwait were being traded on Instagram and other apps.

Surface-level solutions

There is no lack of public commitment to tackling human trafficking among the governments of the region. All six GCC states are signatories to the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, the international instrument to tackle human trafficking, and have written anti-trafficking measures into their legislation. Governments have also partnered with international agencies to tackle the issue. Committees, task forces and strategies abound, and hardly a month goes past without a conference being held to raise awareness of and ‘say no‘ to trafficking.

But despite these commitments, the Global Organized Crime Index identifies that limited progress has been made in tackling these practices on the ground. There are several reasons for this. One is that governments have tended to prioritize the issue of sex trafficking over labour trafficking. In the case of the UAE, Dubai has gained a reputation as a sex trafficking hotspot and the country offers trafficking support services to women and children. However, none are offered to migrant men, who make up the large majority of the country’s workforce. In 2017, Bahrain launched a national referral mechanism to identify and support victims of trafficking, but the procedure is primarily geared towards victims of sex trafficking, and not forced labour (in 2018, the country referred only one forced labour case for prosecution). Although undoubtedly a critically serious issue, the scale of sex trafficking in the region is vastly overshadowed by labour trafficking.

Another reason, which the US State Department has been persistently critical of, is that governments in the region misclassify potential trafficking crimes as administrative labour law violations rather than as criminal offences. As a general rule, where migrant workers have been recruited through regular means and are employed by legitimate entities, abuses against them are dealt with by labour inspectorates rather than law enforcement, regardless of whether they might fall under anti-trafficking legislation. Governments are more aggressive towards black-market ‘visa traders‘, who sell work permits to aspiring migrants, but, all too often, interventions by law enforcement in relation to these issues involve arresting victims of trafficking for immigration violations or for fleeing their sponsors’ homes.

A practice that runs deep

Such failings beg the question of why the Gulf states have not made more progress on implementing their international commitments on trafficking, given that the practice substantially damages their international reputation and that they have ostensibly powerful state institutions capable of and willing to intervene on a range of issues.

A key obstacle is the expectation on the part of business elites – many of whom are closely linked to ruling families – that they can hire, and retain, a low-cost migrant labour force. Many business owners have developed a reliance on migrants and the cheap convenience the Kafala system guarantees. Besides the financial prerogative, there are also social factors: the Kafala system has played a role in sustaining national identities across the region, apportioning enhanced status to citizens as opposed to foreigners. The ability to recruit and depend on foreign domestic workers has in some respects become part of the social contract for Gulf citizens.

Such factors weaken the political will of Gulf governments to seriously tackle the pervasive abuse of migrant workers, and lead to surface-level solutions: laws and regulations issued without real intent to implement them, bilateral agreements with origin states that are non-binding in nature, or enhanced ‘worker welfare’ standards to temporarily cover workers on reputationally sensitive projects such as Dubai’s Expo 2020. Qatar’s labour reform programme, drafted in partnership with the International Labour Organization and agreed to at the height of a political crisis in 2017, when the government was in need of international support, is one rare example of a Gulf state explicitly committing to structural labour reforms. However, the success and sustainability of this programme remains open to question.

For Gulf states to improve their poor rankings for human trafficking in the Organized Crime Index and make a difference to their broader criminality scores, they need to go beyond public-facing anti-trafficking initiatives and talking shops, and start to take seriously the daily exploitation and abuse of millions of workers who service their economies and contribute to their societies. Beyond enforcement activities, this will require overhauling the government structures and systems that allow criminality to thrive in the first place.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index 2021. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.

Subscribe to the GI-TOC Global Organized Crime Index newsletter to get regular updates about the project.

بالرغم من توقيعها على العديد من التعهدات الخاصة بمكافحة كلاً من الاتجار بالبشر والعمالة القسرية، إلا أن حكومات دول الخليج العربي تُعتَبَر مُقَصِرة في مكافحة أكثر أنواع الجرائم انتشاراً في المنطقة.

موضوع رئيسي يَظهَر بشكل بارز مؤشر الجريمة المنظمة العالمي 2021 والصادر عن المبادرة العالمية لمكافحة الجريمة المنظمة العابرة للحدود الوطنية فيما بين الدول الست المُشَكِلة لمجلس التعاون الخليجي، حيث يشير المؤشر إلى أن جريمة الاتجار بالبشر تُعتَبر أكثر الجرائم إنتشاراً في كلٍ من البحرين والكويت وسلطنة عُمان وقطر والمملكة العربية السعودية والإمارات العربية المتحدة. كما أن أربعة من الدول الست أحرزت 8 من أصل 10 نقاط فيما يتعلق بمؤشر جريمة الاتجار بالبشر بالمؤشر الجريمة المنظمة العالمي، وهو ما يعني أن هذه الجريمة تؤثر سلباً على مختلف طوائف المجتمع، كما أنها تُعَد مربحة بشكلٍ كبير ويُحقق السوق بسببها قيمة تراكمية ملحوظة. علماً بأن عدد قليل من المناطق بالعالم تُظهِر أداءً ضعيفاً مثل دول منطقة الخليج بالنسبة لهذا المؤشر.

تُمَثِل هذه التقديرات انعكاساً للمعاناة الإنسانية المنتشرة في منطقة الخليج العربي التي تعتمد دولها بشكلٍ ملحوظ على العمال المهاجرين ذوي الأجور المنخفضة والذين يأتي معظمهم من قارة آسيا وبشكل متزايد مؤخراً من قارة أفريقيا. ويعيش حوالي 30 مليون أجنبي بهذه الدول – أكثر من نصف إجمالي عدد سكان المنطقة – معتمدين على عملهم بنطاق واسع في قطاعات وظيفية متعددة مثل الأعمال المنزلية والضيافة والبناء. ويخضع العمال الأجانب لأنظمة الكفالة التوظيفية الجائرة – التي تنظم العلاقة الوظيفية بين العمال الأجانب وراعي محلي أو ما يعرف بالكفيل – والتي تُقَيدُهم بأصحاب عملهم وتحرمهم من الحق في تكوين اتحادات عُمّالية، كما يواجه العمال الأجانب مجموعة من الانتهاكات منها مصادرة جوازات سفرهم وسرقة أجورهم وتعرضهم للعنف الجسدي. مثل هذه الانتهاكات التي غالباً ما يتم تصنيفها على أنها أحد أشكال العمالة القسرية قد تم توثيقها على نطاق واسع خلال السنوات الأخيرة في قطر استعداداً لكأس العالم 2022، وهو ما أصبح بمثابة مثال ورمز للممارسات المنتشرة في منطقة الخليج العربي.

يَشيع الاتجار بالبشر حين يتم تضليل العمال الأجانب بشكل روتيني والكذب عليهم بشأن الشروط والأحكام الاستغلالية المتعلقة بعمليات توظيفهم، وإجبارهم أيضاً على سداد رسوم باهظة لتأمين حصولهم على الوظائف. وبالرغم من سداد هذه المبالغ في دول المنشأ المُصَدرة للعاملين، إلا أن أصحاب الأعمال في دول الخليج هم من يتمتعون بالمكاسب المالية في أغلب الأحيان نظراً لسدادهم مصروفات توظيف واستقدام منخفضة يتحملها العاملين. كما أنه عند انتهاء فترة عقود العمال الأجانب، يبسط بعض أصحاب العمل سيطرتهم على هؤلاء العمال ويقومون ببيعهم لأصحاب عمل آخرين. وقد أشار تحقيق أجرته هيئة الإذاعة البريطانية (بي بي سي) عام 2019 إلى وجود عدد من حالات الإتجار بعاملات منازل في الكويت عن طريق تطبيق إنستجرام وعدد من التطبيقات الأخرى.

حلول سطحية

لا تفتقد حكومات المنطقة لأُطُر الاتزام العام في مواجهة الاتجار بالبشر، بل أن دول مجلس التعاون الخليجي الست مُوَقِعة بالفعل على بروتوكول الأمم المتحدة لمنع وقمع ومعاقبة الاتجار بالأشخاص الذي يُعَد ميثاقاً دولياً لمكافحة هذه الجريمة، وأَدرَجَت حكومات تلك الدول في تشريعاتها تدابير خاصة بمكافحة الاتجار بالأشخاص. كما دخلت في شراكات مع وكالات دولية لمعالجة هذه القضية، وعززت من إنشاء اللجان وفرق العمل ووضع استراتيجيات مختلفة في هذا الشأن، بالإضافة إلى عقد مؤتمرات بشكل دوري لرفع مستوى الوعي بشأن جريمة الاتجار بالبشر والحث على نبذها.

بالرغم من تلك الالتزامات، أشار مؤشر الجريمة المنظمة العالمي إلى تحقيق دول الخليج لتَقَدُم محدود في مواجهة تلك الممارسات على أرض الواقع نظراً لعدة عوامل، أولها أن الحكومات تميل إلى إعطاء أولوية لقضايا الاتجار بالجنس أكبر من الاتجار بالعمالة. ففي حالة الإمارات العربية المتحدة، نالت مدينة دبي سمعة كبقعة رئيسية لتجارة الجنس وقدمت الحكومة خدمات لدعم ضحايا عمليات الاتجار من النساء والأطفال بينما لم تقدم الدولة خدمات مماثلة للمهاجرين من الرجال الذين يشكلون أغلبية القوى العاملة بالدولة. كما أطلقت البحرين عام 2017 آلية إحالة وطنية لتحديد ودعم ضحايا الاتجار بالبشر، لكن تلك الآلية كانت موجهة في المقام الأول نحو ضحايا الاتجار بالجنس وليس العمل القسري (ففي عام 2018 أحالت الدولة قضية عمل قسري واحدة فقط للقضاء). وعلى الرغم من أن الاتجار بالجنس يُعَد بلا شك أمر خطير للغاية، إلا أنه طغى إلى حد كبير على حجم الاتجار بالعمالة في المنطقة.

ثاني أسباب عدم إحراز تقدم بارز في مواجهة ممارسات الإتجار بالبشر في المنطقة – وهو ما تنتقده وزارة الخارجية الأمريكية بشكل مستمر – يتمثل في أن حكومات دول المنطقة تُصَنِف الجرائم المحتملة للاتجار بالعمالة بشكلٍ خاطئ وتعتبرها مخالفات إدارية لقانون العمل وليست جرائم جنائية. فالقاعدة العامة في هذا الشأن تُشير إلى أنه عند استقطاب العمال المهاجرين من خلال القنوات الشرعية وتوظيفهم من قبل كيانات قانونية، يتم التعامل مع الانتهاكات التي تحدث بحقهم من جانب إدارات التفتيش التابعة للسلطات العمالية وليس قوات إنفاذ القانون، وذلك بغض النظر عن خضوع تلك الانتهاكات لتشريعات مكافحة الاتجار بالبشر. وتتعامل حكومات دول المنطقة بأسلوب أكثر صرامة مع “تجار السوق السوداء للتأشيرات” الذين يبيعون تصاريح العمل للمهاجرين الآملين في الحصول على وظيفة، ولكن في كثير من الأحيان تنتهي مهام قوات إنفاذ القانون في هذه القضايا بإلقاء القبض على ضحايا الاتجار بسبب مخالفة قواعد الهجرة أو بتهمة الهروب من كفلائهم.

ممارسة متأصلة

تثير مثل هذه الإخفاقات التساؤل عن سبب عدم إحراز دول الخليج لمزيداً من التقدم في تنفيذ التزاماتها الدولية بشأن الاتجار بالبشر، حيث أن تلك الممارسات تُضِر بسمعتهم بشكلٍ كبير على المستوى العالمي، علماً بأن هذه الدول تتمتع بمؤسسات قوية ظاهرياً جاهزة وقادرة على التعامل مع العديد من المشكلات.

تتمثل العقبة الرئيسية في اعتقاد صفوة المجتمع بدول الخليج – كثير منهم مُقَرَبون من العائلات المالكة – بأنهم قادرون على توظيف قوة عاملة مهاجرة منخفضة التكلفة والإبقاء عليها، حيث أَظهَرَ العديد من أصحاب الأعمال اعتمادًا على المهاجرين والعمالة قليلة التكاليف التي يوفرها نظام الكفالة. وبالإضافة إلى الامتيازات المالية التي يوفرها النظام، توجد أيضاً عوامل اجتماعية ناتجة عنه مثل دوره في الحفاظ على الهويات الوطنية في جميع أنحاء المنطقة وتحقيق مكانة أكثر تميزاً للمواطنين على حساب الأجانب، كما أصبحت القدرة على توظيف العمالة المحلية الأجنبية والاعتماد عليها في العديد من الأحيان بمثابة عقد أو ميثاق اجتماعي لمواطني دول الخليج.

أدت العوامل المُشار إليها فيما سبق إلى إضعاف الإرادة السياسية لحكومات دول الخليج في التصدي بأسلوب جاد للانتهاكات المنتشرة بحق العمال المهاجرين، وهو ما يؤدي بدوره إلى ظهور حلول سطحية مثل إصدار قوانين وأنظمة دون وجود نية حقيقية لتنفيذها، أو إقامة اتفاقيات ثنائية غير ملزمة مع الدول المصدرة للعمالة، بالإضافة إلى رفع المستوى الخاص بمعايير رعاية العمالة لتأمينهم بشكل مؤقت أثناء إنخراطهم في العمل بمشروعات تمس سمعة الدول مثل ما حدث في معرض إكسبو 2020 بمدينة دبي. كما يعتبر برنامج إصلاح النظام العُمالي في قطر، الذي تمت صياغته بالشراكة مع منظمة العمل الدولية ILO وتم الاتفاق عليه في ذروة أزمة سياسية عام 2017 عندما كانت الحكومة في حاجة إلى الدعم الدولي، أحد الأمثلة النادرة على قيام دولة خليجية بتقديم التزام صريح منها بعمل إصلاحات هيكلية في القطاع العمالي، وبالرغم من ذلك فإن نجاح واستدامة العمل بهذا البرنامج لا يزال محل تساؤل.

ولكي تستطيع دول الخليج أن تُحَسِن من ترتيبها الضعيف بشأن الاتجار بالبشر في مؤشر الجريمة المنظمة وإحداث فارق في تصنيفها الإجرامي بمفهومه الأوسع، فإنها تحتاج إلى تَجَاوُز مرحلة استضافة الحلقات النقاشية والمؤتمرات وأخذ ذمام مبادرات ظاهرية لمكافحة الاتجار بالبشر، وترجمة أقوالها إلى أفعال من خلال البدء في التعامل بشكل جاد مع حالات الإستغلال والإساءة اليومية التي تحدث لملايين العمال الذين يخدمون اقتصادات هذه الدول ويساهمون في بناء مجتمعاتها. وبالإضافة إلى تطبيق ما سبق، سيكون من المطلوب أيضاً القيام بإصلاحات في الكيانات والأنظمة الحكومية التي تسمح للجريمة بالنمو في المقام الأول.

يُعَد هذا التحليل جزء من سلسلة مقالات خاصة بالمبادرة العالمية لمكافحة الجريمة المنظمة العابرة للحدود الوطنية، وتتعمق هذه السلسلة في دراسة نتائج مؤشر الجريمة المنظمة العالمي 2021. كما تبحث السلسلة في تأثير تلك النتائج على صنع السياسات وتدابير مكافحة الجريمة المنظمة والتحليلات من منظور موضوعي أو إقليمي.

اشترك في النشرة الإخبارية للمؤشر الجريمة المنظمة العالمي 2021 الصادر عن المبادرة العالمية لمكافحة الجريمة المنظمة العابرة للحدود الوطنية GI-TOC للحصول على تحديثات منتظمة حول هذا المشروع.