Posted on 07 Dec 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has been used opportunistically by leaders in the Western Balkans to increase their powers through measures adopted to contain the spread of the virus. The result is a weakening of the already feeble checks and balances system in the region, and shrinking space in which civil society can operate to counter organized crime.

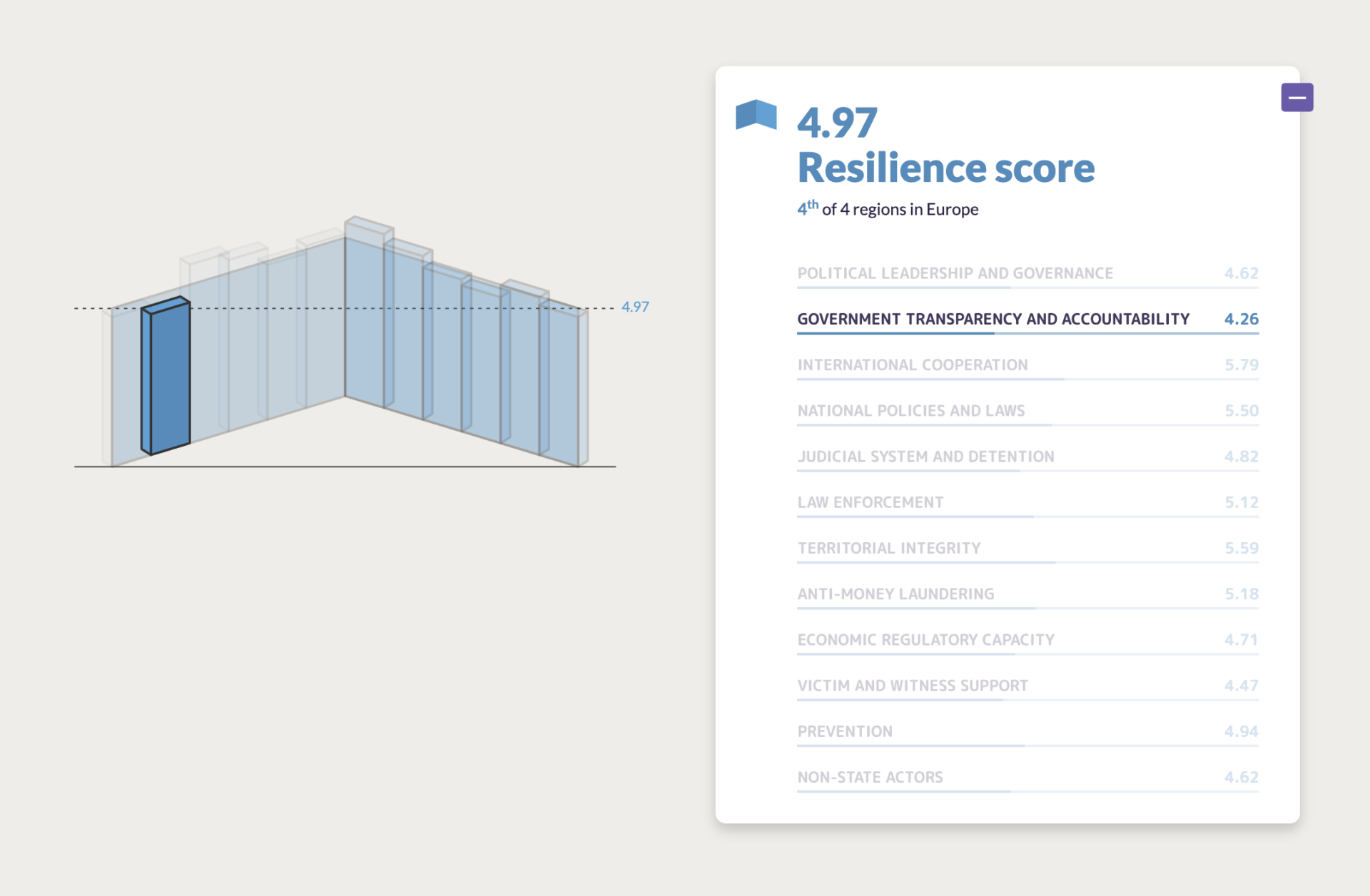

The impact of the pandemic on governance and resilience to organized crime is highlighted in the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC)’s Global Organized Crime Index 2021 (henceforth, ‘the Index’). Resilience to organized crime may have suffered due to the pandemic, and this is the case not only in the Western Balkans, but also other regions globally. Under the Index indicator ‘government transparency and accountability’ – which refers to the degree to which states have developed oversight mechanisms against state collusion in illicit activities – central and eastern Europe (with a regional score of 4.26 out of 10) not only scores the lowest on the continent but falls below the global average (4.41).

The Western Balkans Six (WB6) countries scored even lower on average for the same indicator. Also worrying is the fact that the WB6 countries score poorly on the ‘political leadership and governance’ indicator, which supports the hypothesis that the Western Balkans lack political will to combat corruption and organized crime. As the GI-TOC’s Observatory of Illicit Economies in South Eastern Europe has shown, corrupt governments have weakened the response of civil society to organized crime.

Profiting from the pandemic

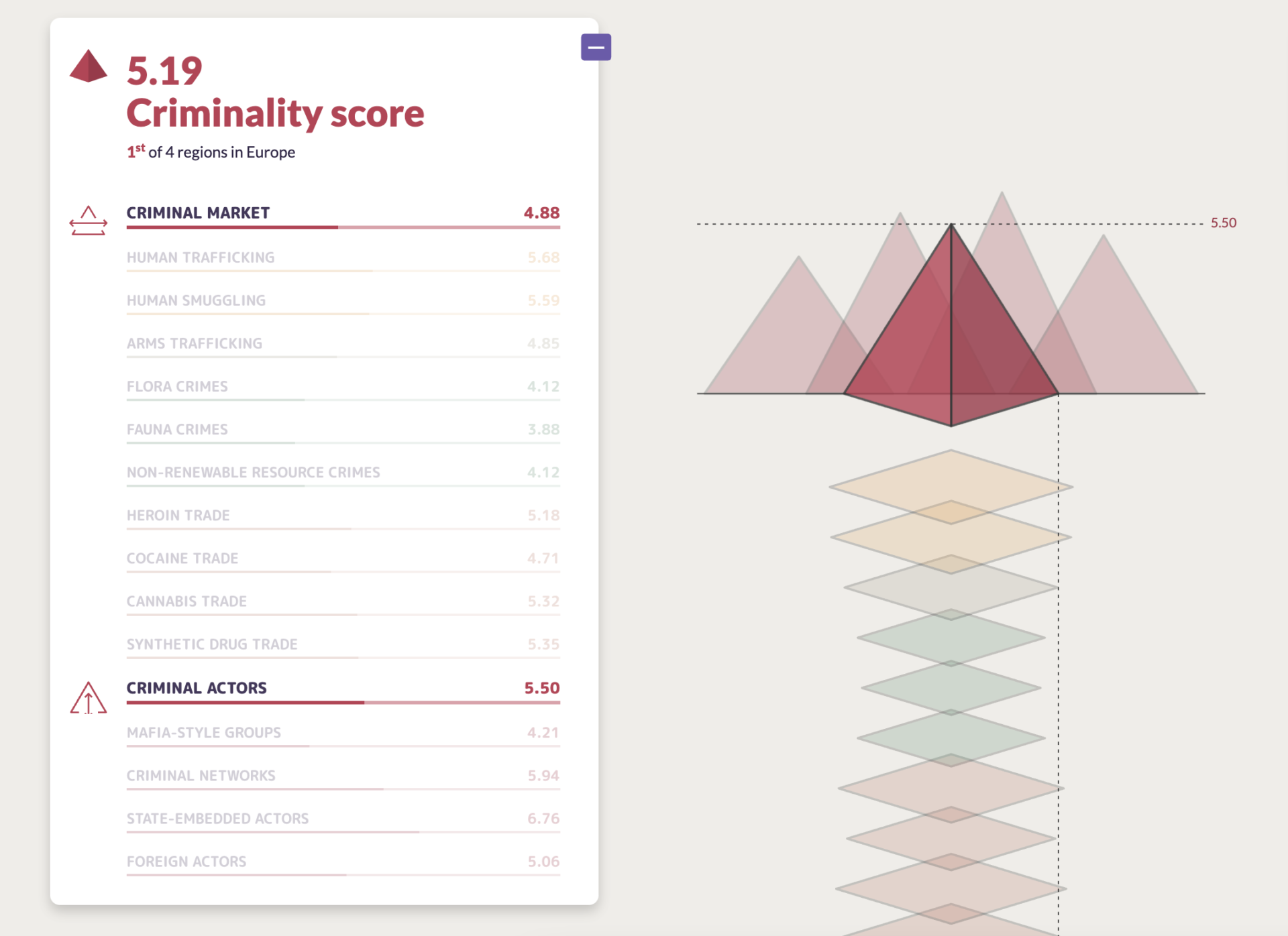

During the early stages of the pandemic, organized crime groups operating in the Western Balkans saw their activities restricted by border closures, which led to a decline in drug availability and price upsurges in Europe. However, they quickly bounced back and reorganized their illegal activities, a trend that was reportedly observed in other regions. Criminal groups diversified into new product markets, such as personal protective equipment, pharmaceuticals, and fake COVID-19 test certificates and vaccines.

The pandemic diverted political rhetoric and resources away from the fight against corruption and organized crime to public health. Criminal actors were quick to adapt to these circumstances and capitalized on the increased vulnerability of communities and businesses that were struggling to stay afloat. Thus, criminal organizations managed to strengthen their positions and gain acceptance and legitimacy among communities in the region stricken by the virus.

The growing influence of these criminal groups is evident in the Index results. Under the tool’s ‘criminal actors’ component, central and eastern Europe ranks as the highest scoring (i.e. most criminal) region in Europe. Montenegro (7.00) and Serbia (6.88) are the states where criminal actors hold the most influence, while the rest of the WB6 follow close suit, rounding out the list of the top 10 highest ‘criminal actors’ scores in Europe. These scores suggest that criminal actor types are deeply entrenched in the region’s social fabric and economy.

Shrinking space for civil society

During the early lockdown phase in March 2020, leaders in the Western Balkans passed new laws, effectively asserting their dominance over the entire state apparatus, under the guise of public health. In Serbia, Montenegro and Albania, for example, leaders introduced measures by decree without parliamentary consultation or scrutiny from the usual participants in a healthy democracy, including the courts, the media, civil society and academia. Although this form of legislating is not unheard of in the region, this autocratic governance approach became more acute as the pandemic unfolded. It has weakened the rule of law and further eroded what remains of citizens’ trust in public institutions throughout the region. The implication is that shrinking space for non-state actors to operate freely may well translate into reduced resilience to organized crime.

Despite the highly restricted environment in which it is forced to operate, civil society is often the last bastion of freedom standing in the way of criminal structures overtaking the levers of power. Such is the situation in the Western Balkans, where despite the low to average ‘non-state actor’ scores recorded in the Index there are still several non-state actors that work hard to challenge corruption and criminality in their countries.

The low scores reflect the environment in which civil society in the region is often forced to operate. Many organizations working on issues related to corruption and organized crime face similar challenges: increased pressure from the state, fundraising challenges and security concerns to engage on countering organized crime.

Opportunities for a renewed policy approach

It is necessary for national authorities and the international community to strengthen the rule of law and the resilience mechanisms identified in the Index to combat organized crime groups in the region. The socio-economic consequences of the pandemic could present an opportunity for stakeholders to redefine medium-term priorities and become more creative in the fight against organized crime and corruption. For example, law enforcement agencies could generate new revenue by taking a tougher stand on asset recovery from organized crime groups and use it to support their investigations.

The European Union and international bodies such as The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development can also play an important role through the financial assistance packages drawn up for the Western Balkan countries to help them limit the economic fallout of the pandemic.

If such financial support were to include conditionality compelling recipient states to address rule of law, transparency and accountability, it would serve to strengthen resilience mechanisms, reversing some of the damages and limitations caused by weakening oversight. These international bodies should use their leverage and leadership to promote these values – especially the European Union, through its macro-financial assistance package and accession conditionality – in response to the latest efforts by leaders to erode the rule of law and democracy in the Western Balkans.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.