Posted on 29 Oct 2024

Profit and power drive organized crime groups. Whether operating cocaine routes through Belgium or the Netherlands, trafficking arms and ammunitions in the Western Balkans, or smuggling humans across the Mediterranean, criminal organizations in Europe generate illicit revenues, which are used to infiltrate the legal economy.

Proceeds from criminal operations are laundered through the purchase of property or businesses, transferring cash offshore, or converting it into cryptocurrency or high-value luxury items, such as cars and yachts. For criminal groups, these assets are not only investments but also symbols of power. For instance, the Italian mafia translates assets into territorial control, which is used, alongside the threat of violence, to take wealth away from communities and maintain control over territories and, therefore, over criminal revenue.

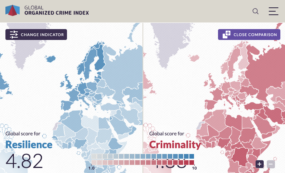

The growth in illicit markets and influence of criminal actors is a global trend. According to the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index, between 2021 and 2023, the overall criminality score in Europe increased from 4.48 to 4.74 out of 10. Eurojust, the EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation, reported that cases involving organized crime groups rose by 12% since 2022. In 2023, Eurojust dealt with more than 13 000 serious cross-border criminal cases, ranging from cybercrime and money laundering, to trafficking in human beings and environmental crimes, and arrested more than 4 200 suspects. These interventions led to criminal assets worth over €1 billion being seized or frozen.

Asset seizure is one of the most effective tools for combating organized crime. It deprives criminals of critical resources, reinforces the rule of law and helps restore public trust in state institutions. However, asset seizure alone does not repair the damage caused by organized crime or bring reparative justice to communities unjustly stripped of their resources. Hence the importance of reusing confiscated goods to benefit society and to implement public programmes, that provide support and compensation to victims of organized crime and repair social ties. The social reuse of assets promotes legal and equitable local development, provides civil society organizations with badly needed resources and helps foster collaboration between state and non-state actors.

The social reuse of assets confiscated from organized criminal groups was the topic of discussion at a conference organized by Libera (an anti-mafia association in Italy) and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences held in the Vatican City on 19−20 September 2024, to which the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) was invited. The GI-TOC’s Global Organized Crime Index considers the social reuse of confiscated assets to be a key measure of prevention, an indicator that influences a country’s levels of resilience, including strengthening support to victims and witnesses and enhancing the role of non-state actors in their anti-organized-crime efforts.

In a special message to the conference, the Pope reminded delegates of the importance of recognizing that ‘asset recovery should not be confined solely to a security policy objective but should also be guided by the principles of restoring and rebuilding the common good’. However, according to the 2023 Index, social protection indicators continue to score lower than most resilience indicators in Europe (as well as globally), highlighting the limited attention given by governments to implementing victim-oriented approaches. Although Europe’s overall resilience scores are higher than those of other continents (scoring 6.27 out of 10), the decline in social protection scores is a concerning trend, suggesting that governments are prioritizing criminal justice-based initiatives over systems aimed at protecting those who are most vulnerable to the impact of organized crime.

Yet, as the Index emphasizes, these different approaches to building resilience are not a zero-sum game. ‘Softer’ responses to organized crime, such as the social reuse of confiscated assets, not only complement security-driven efforts but also increase long-term resilience to criminal threats. The social reuse of confiscated assets contributes to dismantling criminal enterprises and to fostering social ties in local communities, creating a virtuous circle that increases trust in and accountability of public institutions.

In recent years, Europe has introduced several policy and legal initiatives aimed at improving asset seizure and promoting the social reuse of confiscated assets. For example, the EU Directive on Asset Recovery establishes harmonized procedures for tracing, identifying, freezing, confiscating and managing criminal property across the EU. However, the onus is now on member states to show their commitment by implementing the directive and intensifying efforts to ensure that illicit wealth is no longer accessible to criminals.

To date, only 19 EU countries have legislation in place for managing the social reuse of confiscated assets, while legal frameworks that do exist are often unclear or little known. Nevertheless, in addition to Italy, which is a unique case in having practised the social reuse of confiscated goods since the 1990s, there are some success stories from other European countries, including those in south-eastern Europe.

One country that actively promotes the social reuse of confiscated assets is Albania, where assets are assigned to civil society organizations and converted into public goods. For example, cars previously used by drug traffickers were transformed into mobile libraries, to support the education of children in rural areas affected by organized crime, while buildings have been converted into safe spaces for women and girls who are victims of crime and violence. These programmes serve communities by creating jobs and providing services, leading to greater security, education and development. Similar initiatives are found in other Western Balkan countries and in several EU member states, including Spain, France, Belgium and Romania.

Many other countries meanwhile have in place legal frameworks that allow for the confiscation and reuse of assets belonging to criminal groups, but in practice resources are unused and poorly managed. Reasons for this are weak criminal justice systems, poor government transparency and accountability, and slow criminal justice processes.

The social reuse of confiscated assets is a prime example of successful collaboration between government and civil society. Although other areas of resilience need to be strengthened in order to build a comprehensive and sustainable response to the threat of organized crime, reuse of confiscated assets for social and public good sends a strong, symbolic message to criminals, as their most valuable resources – their profits – are stripped and returned to benefit society.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.