Posted on 03 Feb 2023

Chinese criminal syndicates are involved in a number of environmental criminal markets in China and abroad. Despite a solid regulatory framework, authorities must step up efforts to curb the unlawful exploitation of natural resources.

As the world’s most populous country, and with the second-highest GDP and third-largest land area, China is a significant stakeholder in the global economy and is present in virtually all economic sectors worldwide. A major destination for foreign investment since the 1980s, the country is now seeking to centralize its international economic engagement under a single project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). There has been much debate on the positive and negative effects of the BRI, particularly in terms of economic development and environmental impact, and Chinese involvement in environmental crime is of particular concern. The project may facilitate trafficking dynamics witnessed in China or among the Chinese diaspora, aggravating a critical situation for some species and ecosystems.

The results of the Global Organized Crime Index 2021 do not paint a bright picture of China’s involvement in environmental crime. Under the Index, the country ranks first in the world for fauna crimes and – with Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – for flora crimes, with criminality scores of 9 and 8.5, respectively, out of 10. China is a major consumer market for a number of endangered species, which are often seen as symbols of refinement and luxury in certain circles of Chinese society, especially among the rising middle class.

Illicit luxury goods

Fish and seafood are increasingly preferred over pork, once a staple of Chinese cuisine. From less than 5 kilograms per capita in 1980, seafood consumption in China grew to over 40 kilograms per capita in the mid-2010s. The country has emerged as a major player in the fishing sector and Chinese companies seem to be increasingly involved in illicit, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing, as seen in the results of the IUU Fishing Index, where it is the worst-ranked country. Key species have greatly suffered from China’s unregulated appetite for seafood, most notably various species of sharks (whose fins are considered a delicacy in southern China), abalone and totoaba fish, which pirate fishermen target for its bladder. The vaquita, a rare porpoise that lives in Mexican waters, has been driven to the brink of extinction, often caught by trawlers targeting totoaba fish. It is believed that only 30 vaquitas remain in their natural habitat.

Terrestrial species are also under great pressure due to the demand for exotic and rare meats, including tiger and pangolin meat, and bear-cub paws, used mostly as soup ingredients. Species used for this niche cuisine are illicitly imported from South East Asia (or, in the case of pangolins, Africa) or are served to Chinese customers in lawless enclaves in northern Myanmar and Laos that constitute hubs for gambling, money laundering, drugs, weapons and human trafficking.

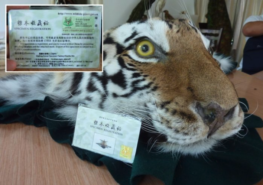

Chinese traditional medicine (TCM) is also an area of concern, as some of the ingredients are sourced from plants and animals that have become critically endangered, including rhinos, elephants, certain cat species and pangolins. Most of these species are protected by China’s national wildlife law, but loopholes are exploited. As much as 91 per cent of online advertisements for pangolin-derived products do not follow federal regulations. Environmental commodities are also used in the luxury sector, with rare woods, ivory and minerals such as jade being used in the furniture and jewellery markets for wealthy customers.

Responses

Chinese organizations, both in the public and private spheres, have taken steps to mitigate the impact of economic development on the environment. Several international NGOs working on wildlife conservation have set up offices in Beijing, sharing findings and recommendations with Chinese law enforcement agencies and other organizations. Chinese and international NGOs are engaging with national tech companies to reduce the number of wildlife-based products advertised on their websites.

Successful anti-smuggling efforts by the Chinese government near main smuggling hubs (Tibet, Dongbei, Yunnan and Guangxi, to name a few), while overwhelmingly focused on drugs and weapons, nonetheless suggest that if awareness-raising efforts continue, authorities can halt illicit wildlife trade activities. In 2021, pharmaceutical executives received prison sentences after being caught laundering imported pangolin scales into the Chinese TCM industry in what was seemingly a strong signal sent to criminal actors within China. The State Forestry and Grasslands Administration, China’s regulatory body that handles wildlife and forestry issues, is currently reviewing its pangolin-scale certification mechanism, a tacit admission that the current system is prone to manipulation and exploitation, contributing to the gradual extinction of pangolins.

Despite these positive initiatives, China must dramatically step up its efforts to curb the illicit wildlife trade and the unlawful exploitation of natural resources in the mainland and abroad. These efforts are especially urgent in the context of the BRI, which seeks to extend Chinese influence abroad, sometimes in countries that have poor environmental crime records themselves.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index 2021. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.