Posted on 23 May 2024

After more than 30 years, in 2023 the UN arms embargo on the government of Somalia was fully lifted. However, questions have been raised about the risks associated with this decision, with many fearing a further proliferation of weapons in a country where instability is widespread, the illicit arms market pervasive and the government lacks full control of its territory.

According to the results of the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index, Somalia hosts one of the most pervasive arms trafficking markets in Africa (scoring 9 points out of 10, an increase of 0.5 points since 2021). The number of illicit weapons circulating in the country, ranging from small arms and light weapons to assault rifles, is significant and involves various types of criminal groups. In addition to local clan militias and transnational criminal networks, militant groups linked to al-Shabaab or the Somali faction of the Islamic State are heavily involved in the market, using weapons to carry out their violent attacks and to engage in other types of trafficking.

Despite these challenges, the UN Security Council (UNSC) decided to end the embargo on the supply of weapons to the Somali government and its security forces (but at the same time extended for one year the sanctions regime, including the arms embargo, imposed on al-Shabaab militants). First imposed by UNSC Resolution 733, on 23 January 1992, the embargo on the Somali government was designed to stem the flow of weapons into the country during the civil war that followed the ousting of President Mohamed Siad Barre. Over the past three decades, the embargo has been amended through subsequent resolutions, and due to improvements observed in the marking and registration of weapons, the proposal to fully lift it was eventually adopted.

The move signalled the belief that Somalia would be able to strengthen its security capacity and provide for its own defence. In the words of the country’s UN envoy, Abukar Dahir Osman, the decision allows the country to ‘bolster the capacity of the Somali security forces by accessing lethal arms and equipment to adequately safeguard [their] citizens and [their] nation’. However, concerns have been raised about the difficulty of consistently implementing a weapons and ammunition management strategy, and calls have been made for Somalia’s neighbours and allies to support the government in its capacity-building process.

The number and security levels of ammunition storage facilities in Somalia are still considered by many to be insufficient, with a risk of leakages from national stockpiles and arms depots. Reportedly, arms diverted to the black market have often ended up in the wrong hands and have been used in attacks by al-Shabaab militants. Sceptics recall how this issue was exacerbated following the partial lifting of the UN arms embargo on Somalia in 2013, which allowed the Somali government to legally import weapons and ammunition up to a prescribed calibre. According to a Reuters investigation, around 35 to 40 per cent of the weapons imported by Mogadishu ended up on the illicit market in the three years following the easing of the embargo.

These considerations have sparked a debate on whether the full lifting of the arms embargo was too premature a decision. The capacity of Somali institutions to handle a larger influx of weapons that would inevitably follow the UNSC resolution has been questioned. Besides concerns around the security of the country’s storage facilities, some argue that the risk of arms being diverted to criminal syndicates or terrorist groups can be linked to a number of structural shortcomings and domestic dynamics that still affect Somalia’s political and social landscape.

One is the presence of clan militias, some of which are reportedly fighting alongside the national army in its military operations against al-Shabaab and have relatively easy access to arms, making the country’s internal situation even more volatile. Given the wavering loyalty of these militias to the Somali security forces, the arms flows that would result from the lifting of the embargo could alter the precarious relationship between them and the federal government, with the collateral effect of intensifying the cycle of violence as clans vie for territorial control and political influence.

This social fragmentation adds to the Somali government’s low level of trust and accountability among its people, which is exacerbated by widespread corruption throughout the state apparatus. Indeed, Somalia is considered one of the most fragile and corrupt countries in the world, with state officials reportedly involved in carrying out or facilitating criminal activities, including arms trafficking.

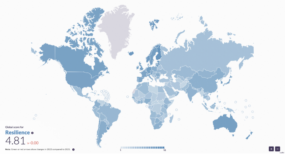

Another major risk is that the Somali government does not fully control all of its ports of entry. According to the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index, Somalia’s territorial integrity was among the country’s lowest scoring indicators (at 1.5 out of 10) within an already weak overall resilience framework (with an average score of 1.79 out of 10). Without effective border control and management of key nodes, such as ports, new arms shipments into the country risk ending up in the arsenals of criminal organizations and militant groups. The existence of unregulated arms markets in the country, where weapons often leaked from federal government stocks are openly sold, is another major problem and underlines the difficulty of controlling and tracing the flow of arms within the country.

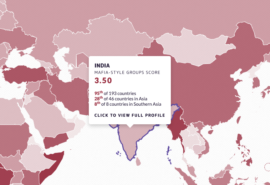

Broader insecurity in East Africa is another factor that will potentially fuel the influx of weapons into Somalia and facilitate the development of extensive arms-trafficking routes. Weapons-smuggling networks are known to extend beyond Somalia’s borders and reach armed groups in neighbouring countries such as Kenya, Sudan and Ethiopia. The recent civil war in Ethiopia has contributed to an escalation in the supply of small arms and light weapons – as evidenced by a sharp increase in the country’s arms trafficking score under the Global Organized Crime Index, from 7 to 8.5. Due to generally inadequate monitoring and patrolling capacities, weapons flow freely across East Africa and increased availability of arms in one country is likely to affect illicit arms markets in neighbouring locations.

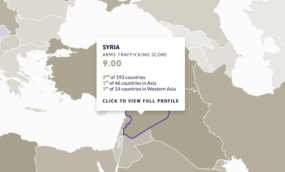

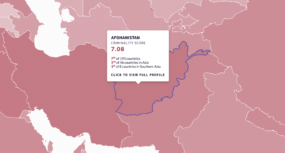

Furthermore, Somalia’s proximity to the unstable Middle East and recent developments in the Red Sea – which has come under recent attacks by Yemen’s Houthis in response to the Israeli campaign against Hamas – are another dangerous source of instability. As these crises drag on, demand for weapons is likely to grow and maritime arms-trafficking networks are likely to become increasingly entrenched. The potential effects of widespread insecurity in Western Asia on the Horn of Africa have been confirmed in recent years by strong evidence of illicit weapons destined for use in the Yemeni civil war reportedly spilling over into Somalia. For example, since December 2020, research in Somalia by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime has documented the presence of weapons such as Type 56-1 assault rifles – allegedly supplied by Iran and destined for the Houthi insurgents but diverted via maritime routes to the northern regions of Somalia.

In this complex landscape, an increase in the volume of weapons entering Somalia after the lifting of the embargo could well exacerbate internal and external problems, ignite an arms race among non-state actors and turn the country into a major arms-trafficking corridor, with potential repercussions for the wider region. Moreover, the expected withdrawal of the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia by the end of 2024 appears to be a further obstacle to the management of security in the country.

Despite these risks, there is a general conviction in the international community that the time has come for the Somali security forces to provide for the defence of their country by any means necessary, including importing military equipment and weapons. However, ensuring that the Somali government can effectively control its borders, regulate its arms markets and secure its own weaponry will be essential to avoid serious security risks in East Africa and beyond.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.