Posted on 23 Apr 2021

Chad, long considered a ‘pillar of stability’ in the Sahel, is at risk as a jostle for power takes place in the country following the death of the country’s long-standing leader, Idriss Déby. The country has been a major hub for trafficking activities and the base for a constellation of regionally active mercenary and bandit groups, many of them centred on vast artisanal gold mines in the north of the country. Déby’s death will reshape the illicit economy and redefine who has control over it, which will have serious implications not only for Chad but the region as a whole.

With more than 6 400 kilometres of mostly porous borders and volatile neighbouring countries such as Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic and Cameroon, over the past two decades Chad has been developing into a major regional hub for trafficking flows and conflict actors.

In the east and south of the country, several armed groups have been profiteering off of activities that range from the smuggling of migrants and vehicles to the trafficking of heroin and cocaine. The situation is even more acute in the remote north-western Tibesti region, where successive discoveries of gold deposits since 2012 have been accompanied by waves of conflict, often predicated on the control of artisanal gold mining and the lucrative desert corridors exploited for bandit predation and drug trafficking.

Since the end of the last war in Libya, between April and June 2020, the situation has been compounded by the return of various Chadian and Sudanese rebel groups engaged in the conflict as guns for hire on both sides of the fighting. These groups have been leveraging the hardware they acquired during their stint in Libya to secure control of lucrative gold mining, trafficking and human smuggling in the region.

Into this troubling context, the death of President Idriss Déby Itno, who ruled over the country since 1990, could unleash a wave of instability in the short term, but also risks laying the ground for various well-primed criminal industries to consolidate their position in the new Chadian landscape.

Déby’s death creates power vacuum in N’Djamena

Déby’s death was announced on 20 April 2021 by the Chadian military. He was said to have died from injuries sustained while fighting rebels from the Front for Change and Concord in Chad (Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad – FACT). Rumours had begun to circulate the night before that he had been injured, though his injuries were earlier described as non-severe ‘flesh wounds.’

Déby’s death came in the context of a FACT offensive, the most serious rebel challenge to Chad’s government since February 2008. FACT, composed largely of Daza Gorane (Tebu) members from the Bahr el-Ghazel and Kanem regions of Chad, has existed since 2016, though for most of this time it has been based in Libya. There, FACT fought alongside the Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF) during their 2019–2020 campaign for Tripoli. This affiliation enabled FACT to become well trained and well armed, and gave them the benefit of support to LAAF-affiliated forces by Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

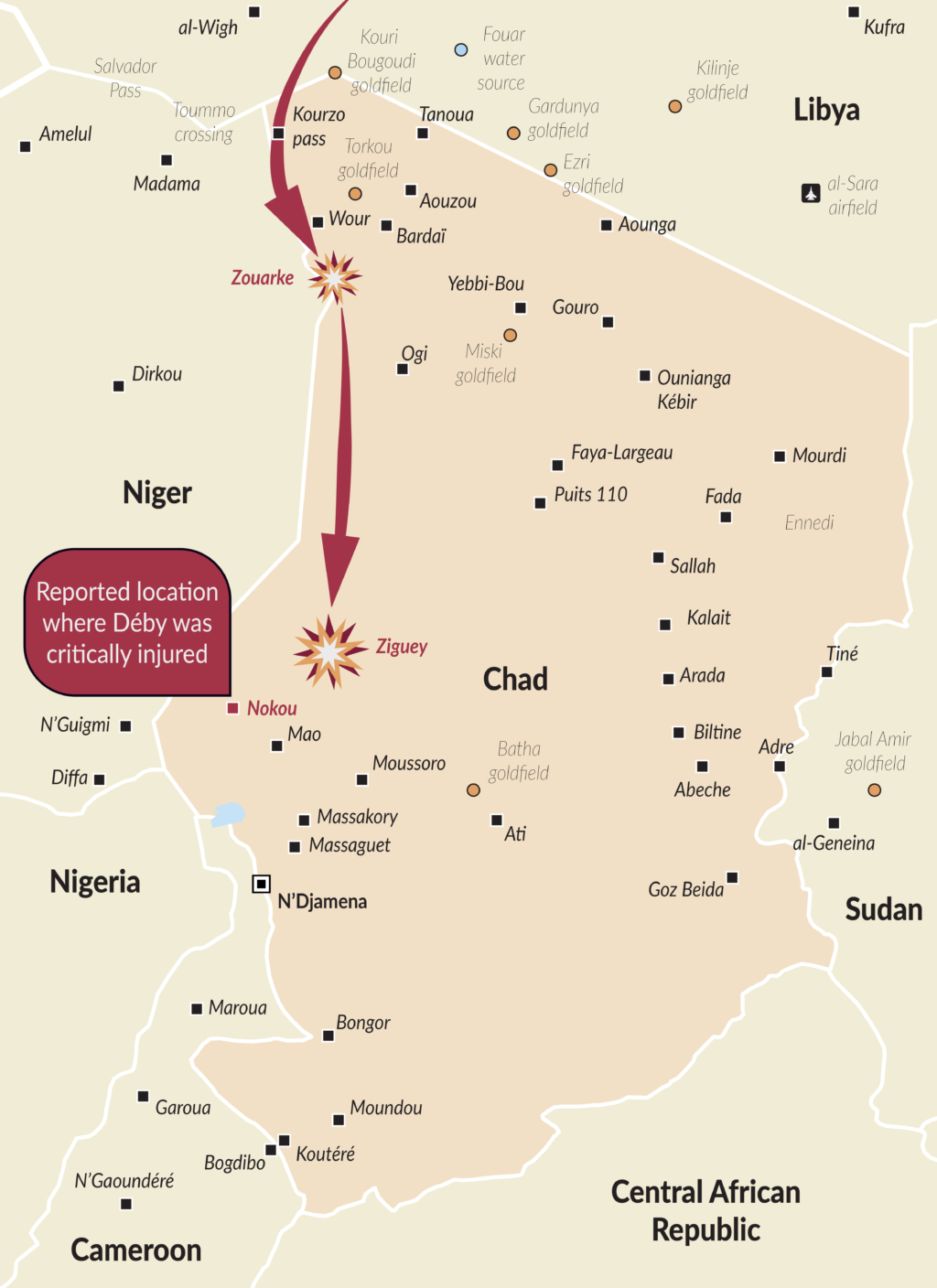

On 11 April, between 800 and 1 000 FACT fighters based in southern Libya invaded Chad via the Kourzo Pass, 65 kilometres south of Libya, on the Nigerien border. The offensive was timed to coincide with presidential elections, which saw Déby re-elected to a sixth term with almost 80% of the votes, though the results were a foregone conclusion even before the polls had opened.

The Armée nationale du Tchad (ANT) tried, at multiple points, to stymie the rebel advance, including with the deployment of Sukhoi Su-25 jets. However, these efforts had little impact, with rebels circumventing army positions in the northern hubs of Wour, Tanoua and the goldfield of Kouri Bougoudi, and hitting one of the Su-25 jets with ground fire, forcing it to return to base.

On 13 April, the rebels attacked Chadian military and customs officers in Zouarke, 300 kilometres south of the Libyan border, forcing government forces to withdraw. After using the neighbouring Goukouni Mountains as a forward base, the rebels then travelled south to the Kanem region, home to several FACT leaders.

Surprisingly, there was no aerial intervention by French forces based in Chad against the rebels. The French have intervened a number of times over the years to eliminate and deter rebel forces threatening Déby’s government, most recently in February 2019.

The FACT formation began to meet heavier resistance on 17 and 18 April, in the Ziguey area in northern Kanem. The area is 300 kilometres north of the capital, N’Djamena. Hundreds of men on both sides died during the battle, including at least five Chadian generals. Despite government casualties, the outcome appeared to be a loss for FACT, which announced a strategic retreat.

Déby reportedly flew by helicopter to the Kanem area, most likely to reinvigorate troop morale after the heavy losses. Although it is unusual for heads of state to position themselves in or near combat zones, Déby has somewhat of a history of such activity. In April 2020, the former president led battlefront troops in Operation Boma’s Wrath after Chadian troops suffered the heaviest defeat yet by Boko Haram, with at least 92 deaths.

It was in Kanem that Déby was either mortally injured or killed. The circumstances surrounding the death are unclear. Information from contacts in Chad suggest that the official military account, which claims that Déby was injured while leading at the front, is unlikely to be true. There are a number of theories as to what actually occurred. The first is that Déby met with FACT leaders on 19 April after a major battle between the two sides. Déby was then killed either at, or immediately after, the meeting.

The second is that Déby was killed by a member of his own entourage. Divisions within Chadian security forces, dominated by Déby’s Zaghawa ethnic group from eastern Chad, have been increasingly pronounced since a February 2019 rebel incursion by the Union des forces de la resistance (UFR). Around 40 rebel vehicles had managed to travel 800 kilometres into Chadian territory until their advance was stopped by airstrikes conducted by French fighter jets. The UFR, led by Déby’s nephew Timane Erdimi, a Zaghawa in exile in Qatar since his failed rebellion in 2009, reportedly accomplished this incursion by convincing many Zaghawa officers to turn against Déby.

The consequences of Déby’s death on politics and security

Although Déby had made no provisions for his succession, the common assumption has been that his son, Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno (aka ‘Kaka’), would take over upon Déby’s eventual death.

As soon as Déby’s death was announced, Kaka was appointed head of a transitional military council, composed of 15 ANT officers (including at least six Zaghawa). The council plans to govern the country for 18 months, during which parliament will be dissolved.

At 37, Mahamat Kaka is currently Africa’s youngest head of state. He faces a number of very difficult challenges, including managing internal struggles and jostles for power within his own family and the military. The most immediate external threat is FACT, with the group announcing on 20 April that they were renewing their offensive on N’Djamena.

Besides, another coalition of Chadian rebels formed on 28 March, composed of several groups. On the same day, FACT entered Chad, it claimed an attack on a Chadian army outpost in Barraka, in the extreme north-west of the country. It is not clear at this stage whether the attack was a distraction to facilitate the FACT incursion, although FACT does not belong to the rebel coalition. None of the rebel groups in the coalition have followed FACT into Chadian territory yet. However, significant instability or weakness in the army in the wake of Déby’s death may embolden them to enter the country and vie for influence and power in N’Djamena.

In the south and south-west, armed groups in the Central African Republic and Boko Haram in Nigeria, could take the opportunity to launch incursions. In the east, Sudanese troops have recently bolstered their position at the border, fearing generalized instability in Chad. According to sources, there is fear that Déby’s death may affect Sudan’s fledgling peace process and the political transition.

Bleak prospects for stability and criminality in the Sahel

Current prospects for stability in Chad are bleak. Déby’s sudden death during a rebellion is the worst-case scenario that most Chadians have been fearing for years. This, because most agree that Déby’s death will result in widespread insecurity as warring actors jostle for power. The fall of Qaddafi in neighbouring Libya and the civil war that ensued serves as a recent reminder of what might unfold in Chad.

It is possible that the ANT will be able to fight off a FACT attack on N’Djamena. Despite its defeats in the north, the force is well armed and experienced, demonstrating in Kanem that it can defeat the rebels in battle. The French, who have proven reluctant recently to support the Chadian government in quelling this rebellion, breaking with the more hawkish stance adopted in 2006 and 2008, and more openly in 2019, could also become more actively involved if key military facilities they operate from in the capital are threatened.

However, regardless of what happens in N’Djamena, it might be difficult to dislodge rebels from areas they have overrun for two reasons.

The first revolves around the rebels’ knowledge of local terrain in north-western Chad as well as their expanding control and profiting from the illicit economy, both of which increase their chances of resisting the Chadian military. Monitoring conducted by the GI-TOC in the region shows that that some of these groups have strong ties with artisanal gold mining, human trafficking as well as drugs and arms trafficking in the wider region, and therefore stand to profit significantly from their territorial gains financially as well as politically.

The failure of the Chadian military to control the Miski area since 2018 is a good indicator of how challenging removing rebels from the area might prove to be. A ‘self-defence committee’ in Miski composed of veteran rebels resisted Chadian ground and air offenses for almost two years under Déby, as they opposed government-led industrial extraction of gold from their area.

With the entrenchment of rebels in the north-west, illicit economic activity is likely to grow following the pattern observed over the past 12 months in respect to gold mining, migrant smuggling, drug trafficking and banditry as armed groups profit from increased instability to expand their activities. This outcome would leave these groups with more resources with which to resist displacement and wage war. The development of these economies would pose complex social and security challenges both locally and to the broader region, and could enable rebel groups to more easily self-fund their activities.

The second reason is that the rebels have no incentive to return to southern Libya. The current peace process and prospective return of a state in Libya means that Chadian rebel groups will not be welcome there in the medium to long term. Local militias in southern Libya are likely to adopt policing roles and gain legitimacy locally by chasing out Chadian rebel groups, often described by locals in southern Libya as ‘bandits’. Over time, this could result in the gradual shift of the epicentre of organized crime from southern Libya to the Tibesti region.

Southern Libya has been a safe haven for rebel groups since the 2010 Chad–Sudan entente and the fall of Qaddafi in 2011. The area’s strategic geographic location on the border with Chad and close to Niger, has allowed some Chadian rebel groups to profit from the gold mining economies in Kouri Bougoudi and Kilinje, and to participate in or prey upon high-value trans-Sahelian illicit economies, such as the trafficking of cocaine and cannabis resin.

A medium-to-long-term shift in stance vis-à-vis Chad’s role in multilateral coalitions could also come about, depending on the leadership. Only recently, in February 2021, Déby had committed to sending 1 200 troops to fight jihadists in the ‘three-border’ region of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso as part of the G5 Sahel initiative. Rumours emerged on 20 April that some troops assigned to the G5 forces in Niger were returning to Chad.

Prolonged insecurity in Chad, or events that lead Chadian forces to return home from deployments in Niger and Mali could have a serious impact on security in those countries. Since 2011, Chadian forces have played a key security role in the Sahel, combating Boko Haram, ISIS and JNIM, as part of the G5 Sahel, of which Déby was the current president, and in UN missions such as MINUSMA in Mali. In the short term, the removal of Chadian forces from these formations would be likely to lead to a void that could be exploited by jihadists and other armed actors.

Such a security void could have a substantial impact on organized crime in the Sahel. It could further enable efforts by Moroccan and Latin American drug traffickers to move shipments of hashish and cocaine across the region, potentially further fuelling a recent rise in cocaine shipments through West Africa.

Even if the new transitional military council manages to cling to power in the medium to long term, illicit economies may still flourish given the well-documented involvement of military officers in the drug trade. The latest major episode evidencing this collusion came in July 2020, when 10 security officers, including a general, two colonels and a high-ranking intelligence official were sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment for their involvement in a drug trafficking ring, helping to convey Tramadol from Douala, Cameroon, and Cotonou, Benin, to Libya, via Chad.

As events continue to unfold, there will be a number of key issues to watch in terms of the illicit economy: the movement of key militias into vulnerable zones; the impact on migration flows and migrant safety; and the repositioning of the Chadian elite around specific choke points. Similarly, monitoring the illicit economy during the period may provide clues as to how alignments and power dynamics are reshaping themselves following the vacuum left by Déby’s death.

Background on FACT

Creation

Mahmat Mahadi Ali (often referred to as ‘Mahdi’), a veteran from the Movement for Democracy and Justice in Chad, is the founder of FACT, a rebel movement mostly composed of Daza Gorane (Tebu) members from the Bar el Gazel and Kanem regions of Chad.

Mahdi has had a strained relationship with other rebel groups since his movement’s inception. Most rebels have considered him to be tribalistic, that ‘he divided people and paid too much attention to tribe over nation’. He betrayed the UFDD, led by Mahammat Nouri, by creating FACT, born out of a violent clash between his men and the UFDD in April 2016. Hakimi had reunited the Chadian rebels in the Fezzan under the UFDD banner for Nouri. Based in France, Nouri was arrested by French authorities in June 2019 on suspicion of crimes against humanity. He was later released on sanitary grounds due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nouri later sent Mahdi to take over the UFDD leadership in Jufra, Libya. Nouri reportedly saw Mahdi, who was also based in France and the UFDD’s ‘secretary general’ as more of a political leader than Hakimi, a veteran fighter. Realizing that most rebels reunited for Nouri were from the Bahr el Gazel and Kanem regions of Chad, while Nouri was from Bourkou, Mahdi started placing his close ones in key strategic roles, before eventually breaking away to create FACT. A battle between warring rebel factions broke out in Jufra, causing dozens of deaths. Hakimi fighters won the fight and left for Sebha, creating the CCMSR rebel group with Mahamat Hassan Boulmaye, who was once a spokesperson for UFDD. They left Mahdi in Jufra with less than 10 vehicles. FACT has been involved in trafficking and mercenary work ever since.

Role in the war in Libya

Mahdi’s FACT was actively involved on the front lines of the war on Tripoli, which broke out in April 2019, siding with the LAAF of Marshal Khalifa Haftar. Mahdi and Haftar’s links have been described as opportunistic at best, centred on the war effort. Haftar’s relationship with Hakimi (who joined Déby’s ranks) were described as stronger, for instance. Haftar bombed Mahdi’s positions in Jufra in December 2016, causing one reported death, according to a FACT statement. Before Haftar, Mahdi had sided with Misrata, although the relationship became strained from mid-2017, coinciding with the departure of the Misratan Third Force and arrival of the LAAF in Jufra.

Between mid-2017 and late 2018, FACT maintained an inferred neutrality agreement with the LAAF, mostly entertaining a quasi-policing role in Jufra – both securing roads against bandits but also periodically attacking Islamic State positions. It is perhaps this anti-IS stance, described as opportunistic by many contacts, that facilitated cooperation with Haftar, but could have severed ties between Haftar and Déby, given Haftar’s refusal to fight FACT.

In early March 2021, relations with Haftar-affiliated brigades in Jufra and Fezzan, including the 128th Brigade in particular, became strained because of disagreement on fuel-smuggling revenues and hierarchy. Many of the FACT rebels then relocated from Jufra to bases around Um al-Aranib, closer to the Chadian border.

FACT’s total force in southern Libya is estimated at around 1 000-2 000 fighters by several contacts and 300–500 vehicles, acquired while fighting alongside Haftar’s LAAF during their offensive on Tripoli. Videos circulating online in mid-April also suggest FACT may be in possession of a helicopter gunship. Contacts report that FACT has forces that have stayed back in southern Libya during the incursion, notably close to Um-al-Aranib.

Photo credits: Paul Kagame, Meeting with President Déby of Chad, Chairperson of the African Union | Kigali, 22 June 2016