Posted on 20 May 2020

Mafia bosses ‘free to come and go as they please’. Italy’s prison system has been plunged into crisis by the pandemic – and by the mafia. The country’s crime syndicates may have emerged healthier for it.

On 21 February 2020, the first person to be tested positive for COVID-19 in Italy was discovered in Codogno, a small town in the northern province of Lombardy. We now know that the novel coronavirus had been present in Italy well before that date. At the time of writing, Italy had registered over 200 000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with the total number of fatalities approaching 28 000. The damage caused by the virus, both to public health and the economy, is unprecedented in more than a century. And, as with all national emergencies, the mafia have added to the disruption, and taken advantage of it.

From 7 to 9 March, a crisis rocked Italy when the country witnessed a number of prison riots, in some cases leading to outbreaks. The violence was triggered by two main catalysts: a COVID-related ban on family visits and increasing risk of contagion among the prison population. But these were not the only factors that led to Italy’s prison crisis: around six weeks later, the announcement that there would be an imminent release of numerous mafia bosses on health grounds caused widespread outrage.

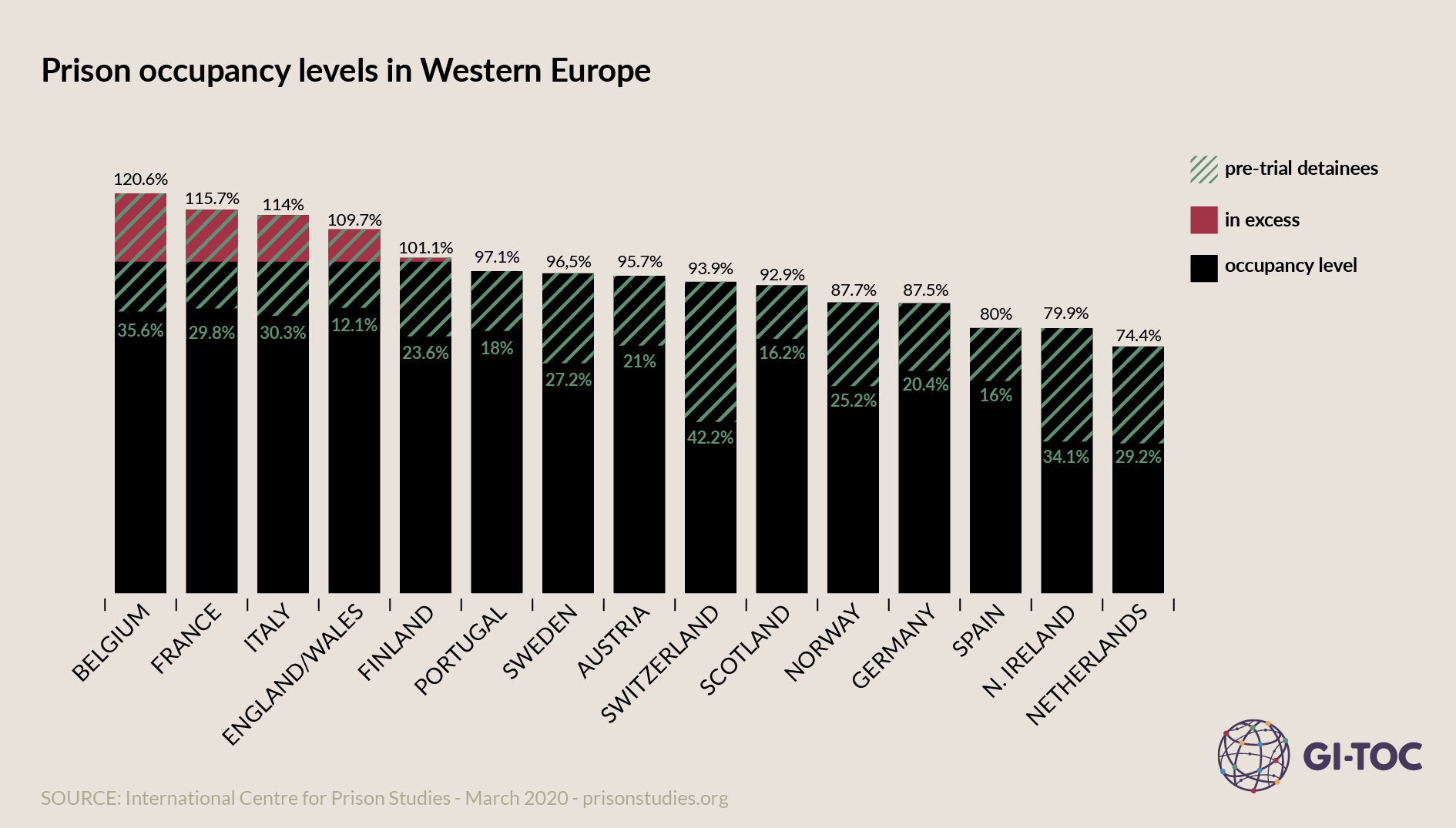

Italy has one of the largest prison populations in Europe and has long struggled with overcrowding in its correctional facilities, largely as a result of the high number of pre-trial detainees. This is one of the greatest challenges facing the prison system in Italy. In 2013, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that overcrowding in the country’s prisons violated basic rights.

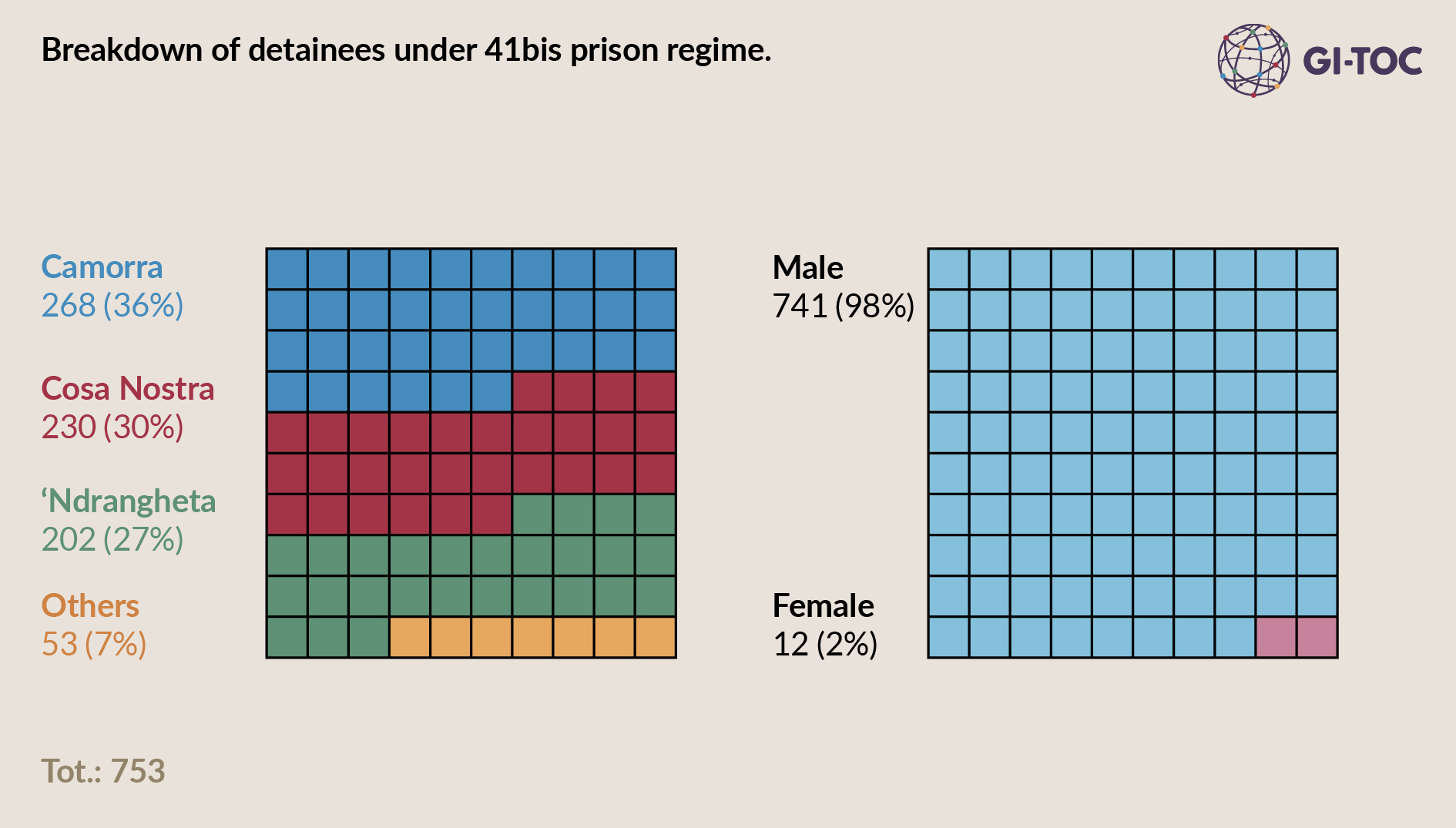

Another contentious issue in the Italian prison system is the so-called ’41-bis’ regime, a special high-security detention system for prisoners convicted of mafia-related or terrorist offences. The regime (which gets its name from Article 41b of the Prison Administration Act) is reserved for the most dangerous mafia bosses and provides for the complete isolation of prisoners, who are permitted no contact with the outside world.

As of November 2019, just a few months before the outbreak of the pandemic, there were 753 prisoners (741 male and 12 female) in Italy detained under this high-security regime. The vast majority had been convicted for mafia-linked offences.

At that time, of this segment of the prison population, 268 were from the Camorra (a mafia syndicate from the Naples and Campania region); 230 from the Cosa Nostra (the Sicilian mafia); and 202 from the ‘Ndrangheta (a branch associated with the country’s southern Calabria region). The remaining detainees are those with links to the other organized crime groups, such as the Stidda, the Sacra Corona Unita and others.

The 41-bis prison regime is the subject of much debate at both a national and European level. In 2007, an American judge denied Italy’s extradition request for mafia boss Rosario Gambino, on the grounds that the prison regime was tantamount to torture, citing the UN Convention against Torture. The most recent case to reignite the heated debate was that of mafioso Marcello Viola in 2019, in which the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decided that the provision of prison benefits should be afforded to even those prisoners who did not cooperate with the authorities, who were hitherto excluded from such benefits. It was argued that collaboration with the state cannot be the only means of evaluating a prisoner.

However, the 41-bis prison regime is not only constitutional, it is deemed by many as necessary. Italy is home to a number of high-profile criminals, hence the uniqueness of the country’s anti-mafia legislation, and decisions by the ECtHR, or a judge from the United States, might appear to some as underestimating the potential risks associated with the loosening of restrictions on mafia bosses.

Citizens locked up, inmates break free

Two days before the Italian prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, announced a nationwide lockdown, part of the government’s measures to counter the pandemic, violent riots spontaneously erupted in Italian prisons across the peninsula on Saturday 7 March. The protests, linked to overcrowding and fears surrounding the spread of the disease, would continue throughout the weekend, with sporadic episodes of violence erupting for several weeks afterwards.

Italian citizens, now confined to their homes by law, watched images broadcast of jailbreaks, prisons ablaze and battalions of law-enforcement officers struggling to maintain law and order, both inside prisons and outside. During those few days, it appeared as though the worst-case scenario was materializing – that the country’s democratic order was on the brink of collapse.

By 11 March, 14 prisoners had died during the riots and hundreds of prison officers were injured. The damage to property amounted to tens of millions of euros and reduced the prison system’s capacity by 2 000, the first tangible consequence of the riots. However, in the mind of the public, one of the most critical events was the escape of 72 inmates from a prison in the south-eastern town of Foggia, including a number of dangerous mafiosi. In the 48 hours that followed, law enforcement was able to round up 61 of them in an unprecedented manhunt, the likes of which had never been seen in the history of the Italian Republic. But many were still at large, and, like the pandemic itself, which had been steadily infiltrating the sinews of society, the public panic generated by the prison outbreaks and riots went viral on messaging services. Images of buildings on fire, prisoners on the run and mobs of detainees destroying prison cells were frenziedly shared by millions of Italians across the country.

The social-media messaging and videos gave the impression that the state was losing control of the prison system, the place of security that separates the good from the bad, the citizens from the criminals. Just as the coronavirus was tearing through the population, there was a fear that so too would the criminals.

‘I have no doubt that it was the mafia that orchestrated the meticulously planned riots,’ said a veteran investigator specializing in the prison system, who wished to remain anonymous. ‘As soon as the riots started, the relatives of the prisoners were immediately outside protesting – it was almost as if they knew. They did know, that is certain. They coordinated and attacked as a group.’

That mafia inmates may have started the riots is a credible theory – after all, mobile phones have been discovered in high-security sections in some prisons holding 41-bis prisoners, and investigations are ongoing into the mechanisms that enabled them to be smuggled in. The ultimate objective of mafia groups within the prison system is to maintain their grip on control of their networks by communicating with the outside world. In the words of a senior prison officer, such prisoners are ‘continually sustained by their criminal world’. And, as previous experience has shown, mafia groups take advantage of emergencies. In the case of the 1980 earthquake in Irpinia, southern Italy, a source estimates that a significant portion of the 26 billion euros spent on reconstruction was used to enrich Camorra clans such as the Casalesi.

After the escape, the release

The timing could not have been more inauspicious. Just weeks after the prison uprising, a memo sent by the department of penitentiary administration alluding to the potential release of mafia bosses from prison on grounds of ill-health came as a second blow for the Italian public, still reeling from the recent riots in which scores of prisoners had managed to escape. The memo from the department requested prison directors to disclose the names of all detainees with underlying health conditions in order to assess appropriate measures to be taken should the prison service not be able to provide necessary healthcare. Adequate health facilities are severely lacking in Italy’s straining prison system.

As a source from the Ministry of Justice (under which the department of penitentiary administration falls) clarified: ‘The document in itself does not release the prisoners – this is clear. But facing us is a mafia that knows how to take advantage of every tiny concession made. … Prisoners detained under the 41-bis regime are safe, they are isolated. But many of them are in ill-health and need care, which means, if the prison authorities cannot provide it, it is down to us.’

Although the department of penitentiary administration, in response to public outcry at the notion of a potential release of a number of mafiosi, sent a statement on 20 April clarifying that it had not issued any provision regarding the release of high-security prisoners (and claiming it was just a ‘monitoring exercise’), it seems likely that mafia bosses’ lawyers identified a gap in the regulations that has permitted them to submit release requests for their clients, especially those above the age of 70. These are by and large the so-called ‘old bosses’. Among them are the capi dei capi – the most senior bosses of the Cosa Nostra, the Camorra and the ‘Ndrangheta.

Several were released. On 10 April, Rocco Santo Filippone, on trial for ordering the bombings that killed two Carabinieri in 1994, was allowed free. Sick and elderly, the ‘Ndrangheta boss was placed under house arrest without so much as an electronic tag. On 22 April, Francesco Bonura, due for release 11 months later, was freed on the grounds of serious health issues. Two days later, on 24 April, Pasquale Zagaria, the economic brains of the Casalesi clan, was set free. Zagaria, who was serving his sentence under the 41-bis regime, has cancer. However, given there is no hospital capable of treating him, as a result of hospital beds being prioritized for Italy’s acute COVID-19 emergency, Zagaria was sent to serve the rest of his sentence under house arrest in Pontevico, Lombardy.

The decision to release these prisoners has provoked severe criticism from many, including one anti-mafia magistrate: ‘It is absolute insanity, a grave error. [Zagaria] could have been moved to a military plane in order to provide him with all necessary treatment, and then returned to the prison. Or a different high-security prison with the capacity to treat him could have been found. Under no circumstances should he have been offered any concessions whatsoever. It sends such a terrible message to the country. … we’re talking about a criminal economics mastermind, so he is even more dangerous than most. This simply sends a message to our citizens that while they are prisoners in their own homes, mafia bosses are free to come and go as they please.’

At the time of writing, the most notorious Camorra boss alive, Raffaele Cutolo, detained under the 41-bis regime since 1993, is awaiting a decision on his potential release from prison. Cutolo, a ‘super boss’ of the Italian mafia, now elderly and in ill-health, has never submitted an appeal, has never shown remorse for his crimes (he is serving multiple life sentences for murder) and has never cooperated with the state. He has considerable inside knowledge. His release would have a devastating effect on the whole of society in Italy.

While Italy has struggled to cope with the COVID-19 emergency, as have many other European countries, Italian mafia groups have managed the emergency to perfection. Their resolute determination and capacity to coordinate activities illustrates not only the danger they pose, but also their ability to seize opportunities as soon as they arise. Just two weeks after the first confirmed coronavirus case in Italy, the mafia orchestrated some of the most extensive prison riots in Italy’s history, showing how they are attuned to the difficulties facing the country in a state of emergency. They have also shown their intricate knowledge of the country’s legislation governing the regulations of prisons. They were able to secure access to communication and information, resulting in a number of prison releases for senior members of their syndicates.

The mafia are always one step ahead of law enforcement. They understand, and can therefore manipulate, the bureaucratic norms that regulate law and institutions. The mafia have handled the emergency just as well as the scientists employed to counter it, leveraging the crisis to their advantage, to the consternation of law-abiding Italian people. Like the virus itself, the mafia have been able to risk infecting society. Each unmonitored phone call is a win for them; every prisoner released is a victory. The mafia were not intimidated by the pandemic because they knew they had the capacity to exploit it to their own advantage.

Since the beginning of the crisis, a total of 376 prisoners either convicted of mafia-type offences or in pre-trial detention have been released under house arrest, four of whom were detained under the 41-bis high-security prison regime, including Camorra boss Pasquale Zagaria, two Cosa Nostra bosses, Francesco Bonura and Vincenzo Di Piazza, and an ‘Ndrangheta boss, Vincenzo Iannazzo. A further 456 prisoners submitted requests to be released under house arrest.

On 2 May, the head of the department of penitentiary administration, under whose watch the riots and the prison releases occurred, resigned. His replacement is Bernardo ‘Dino’ Petralia, a public prosecutor and a man described by the Minister of Justice as having ‘dedicated his entire career to justice and the fight against the mafia’. Petralia was the magistrate behind the discovery of one of the largest drug refineries belonging to the mafia in the 1980s. The deputy head of the department is Roberto Tartaglia, one of the leading figures in the investigations into the state-mafia pact. The new appointments send a strong message that the state will act decisively against the mafia and any notion of prison releases.

The prisons crisis in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic is tantamount to an instruction manual of errors to avoid and opportunities the mafia are able to seize. Italy’s crime bosses have been able to exploit the emergency so well for one simple reason: deadly viruses know how to recognize and respect each other.

Translation, review and data collection by Lyes Tagziria and Ruggero Scaturro