Posted on 24 Apr 2024

Extortion is a rapidly worsening problem throughout South Africa. This is the first in a series of reports tracking its spread across the country. The Western Cape, an economic hub with a long history of gang violence and extortion, is particularly hard hit. The City of Cape Town is host to a menacing shadow economy, with money, services and goods being extorted from an increasingly wide range of businesses, including spaza shops, nightclubs, construction and transport companies, as well as individuals.

The issue has been widely reported in the media and it is clear that many people are justifiably concerned. However, the reality of the situation is far more serious than is perhaps realized. Extortion is growing rapidly and spreading throughout the city, and the groups involved are highly organized. The range of sectors and people affected is widening: from street vendors selling their wares in Mitchells Plain or Khayelitsha, to the owners of bars and restaurants in the city centre; from construction companies building roads or houses, to municipal workers and contractors providing basic services. In certain parts of the city, even private vehicles have become targets.

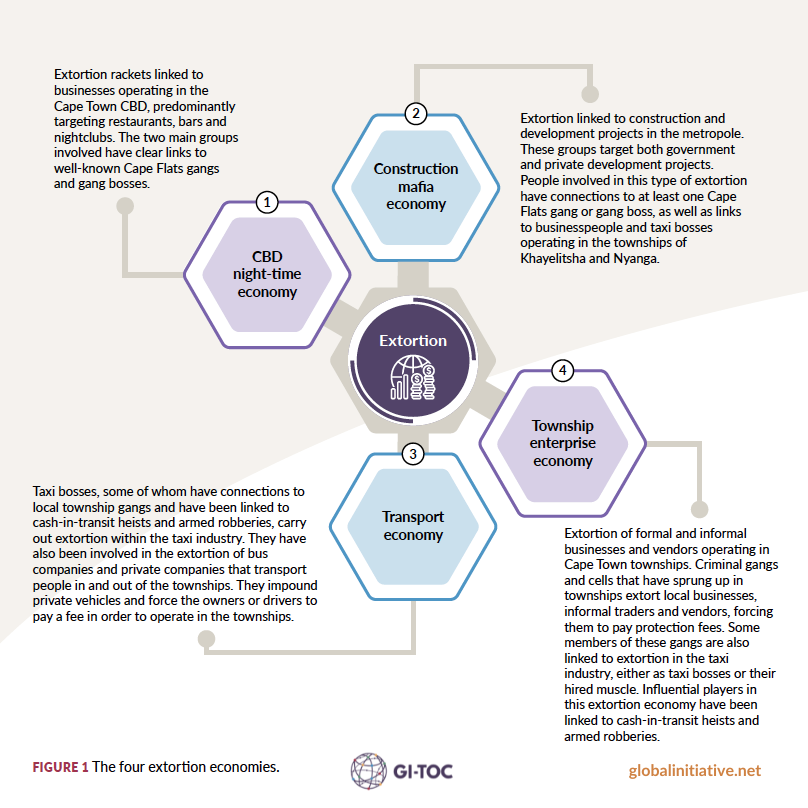

The GI-TOC has identified four main extortion economies for the focus of this report:

- The central business district (CBD) night-time extortion economy. While initially focused on the city’s night-time economy, extortion activities have expanded to include other businesses, such as restaurants and coffee shops.

- Cape Town’s construction mafia. These groups target infrastructure projects and the construction sector. Methods have been copied and adapted from KwaZulu-Natal, and similar extortion practices have spread to other parts of the country.

- The transport extortion economy. This has long existed within the minibus taxi industry in Cape Town, but has expanded in an unprecedented way to include buses, private transport and even private vehicles.

- The township enterprise extortion economy. This focuses on formal and informal businesses and individuals operating particularly in the Cape Flats, including the townships of Khayelitsha, Gugulethu and Nyanga. It also targets municipal workers and contractors.

While these four extortion economies are clearly distinct, they are also interlinked, and criminal actors move between them. For example, some figures within the CBD night-time extortion economy are also involved in the construction mafia, transport extortion and, in areas under their control, particularly on the Cape Flats, the township enterprise extortion economy. Similarly, individuals involved in extortion in townships such as Khayelitsha and Gugulethu may have connections in the construction mafia or transport extortion. In addition, extortionists will often also engage in other forms of criminal activity, such as the illicit trade in firearms and drugs or armed robbery (Figure 2).

Extortion is a learned practice, and connections such as these enable those involved to hone their skills and refine their methods. Lessons are also learnt from extortion practices in other parts of the country, as in the case of the Cape Town construction mafia. Methods developed in the Cape are also exported throughout South Africa as individuals move between provinces. The result is a criminal web of extortion, in which actors learn from each other and move freely between operations.

Another key risk posed by the Cape Town extortion economy is that is it becoming increasingly entrenched. The CBD night-time extortion economy, for example, has existed for more than two decades and has become normalized, with some actors now expanding into other sectors. Moreover, township enterprise extortion, which began much more recently, has become pervasive and widely accepted in a relatively short period of time. International research indicates that once extortion economies become entrenched, they are extremely difficult to deal with. This is a major concern – not just for Cape Town, but for the province and the country as a whole.

Methodology

This research focuses on identifying the types of extortion that have developed in Cape Town and understanding how they operate. It also examines the factors that have contributed to the entrenchment and growth of extortion, and the various actors and groups involved. The report also looks at the links between extortion and other illicit activities, as well as the infiltration of government institutions, and outlines some responses. Finally, it recommends steps to be taken to address the problem.

This report builds on previous analysis and fieldwork undertaken by the GI-TOC on extortion practices in Cape Town. Structured and unstructured interviews and engagements were conducted with various role players and actors, including community groups, individuals and officials. While some people took part openly, others were more reticent, fearing reprisals if their participation became known. Some agreed to participate only on condition of anonymity.

This is intended to be the first in a series of reports the GI-TOC will produce on extortion economies throughout South Africa, the aim being to gain a better understanding of how and why this criminal activity is increasing. The series will examine how extortion practices vary across the country, and put forward local and national solutions.

Understanding extortion in the South African context

Extortion is the practice of obtaining money, goods or services through the use of actual or implied violence or force. The offence is not defined in South African legislation, but a common law description has developed through historical legal influences. The SAPS uses the widely accepted denotation of extortion as ‘taking from another some patrimonial or non-patrimonial advantage by intentionally and unlawfully subjecting that person to pressure which induces him or her to submit to the taking’.

At a Business Against Crime South Africa conference in Cape Town, Mervyn Menigo of the National Prosecuting Authority explained the concept of implied threat by using the example of a gang member visiting someone’s home and demanding something from them, pointing out that the awareness of his social standing would be sufficiently threatening. ‘People think he must threaten me with death before I make a case. It’s not [the case]; it’s the pressure,’ Menigo said, adding: ‘Even if a victim of extortion refuses to succumb to the demands, it is still a crime, and considered attempted extortion.’

Extortion requires the victim’s consent, even if it is obtained illegally. Victims often avoid reporting the crime, as they do not want people to know that they agreed to the perpetrator’s demands. It also goes unreported due to fear and intimidation. These factors contribute to its normalization, as extortion becomes seen as a cost of doing business, operating or living in a particular area, and can also lead to an increase in the frequency and size of the demands.

Subscribe to the East and Southern Africa Observatory dedicated mailing list