Posted on 14 Jul 2025

Violence in Brazil’s northern and north-eastern regions is a growing concern. In 2023, the homicide rate in northern Brazil was 41.5% higher than the national average. Meanwhile, six of the 10 cities with the highest homicide rates in the country in 2023 were in the north-eastern state of Bahia. Rising insecurity in these regions has been driven by the country’s two mafia-style groups, Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and Comando Vermelho (CV), moving into these areas.

The Brazilian government is seeking to address this violence by proposing a constitutional amendment to reform public security. The bill, which is currently being debated in congress, aims to standardize police operational strategies and codes of conduct across Brazil’s 27 states to bolster enforcement efforts against organized crime.

Alongside this proposal, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration suggested launching a pilot programme in Bahia in December 2024 to address the state’s public security crisis. The programme would provide local law enforcement with federal intelligence and technical guidance from academic researchers to help them displace criminal networks from their territories. However, the Bahia state government refused federal assistance on the grounds that organized crime is not the main public security problem in the state, a justification that is not backed up by existing data. The evidence shows that criminal networks are potent and highly time-sensitive drivers of lethal violence in Bahia and Brazil more broadly.

Organized crime moves north

In the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index (‘the Index’), Brazil’s mafia-style group indicator score was 8 out of 10, placing the country second in South America, after Colombia and Venezuela (9.5), for this category of criminal actor. These large criminal groups from the south-eastern region of Brazil have increased their footprint across the country with two goals in mind: establishing new routes for transnational drug exports and diversifying their revenue streams into other profitable illicit trades, including wildlife trafficking and illicit gold mining in the resource-rich Amazon region, and extortion and protection racketeering in densely populated urban margins.

At the core of the expansion of the PCC and the CV is their willingness to cooperate with smaller, local criminal networks. In exchange for allowing the PCC and CV to move into their turfs, these smaller groups receive weapons and cash. This support has empowered the local groups, which were previously limited to low-level drug retailing, to govern communities, influence public security and confront the state. Compared to the 2021 iteration, the 2023 Index saw an increase of 0.5 points for criminal networks in Brazil, placing the country well above the global average.

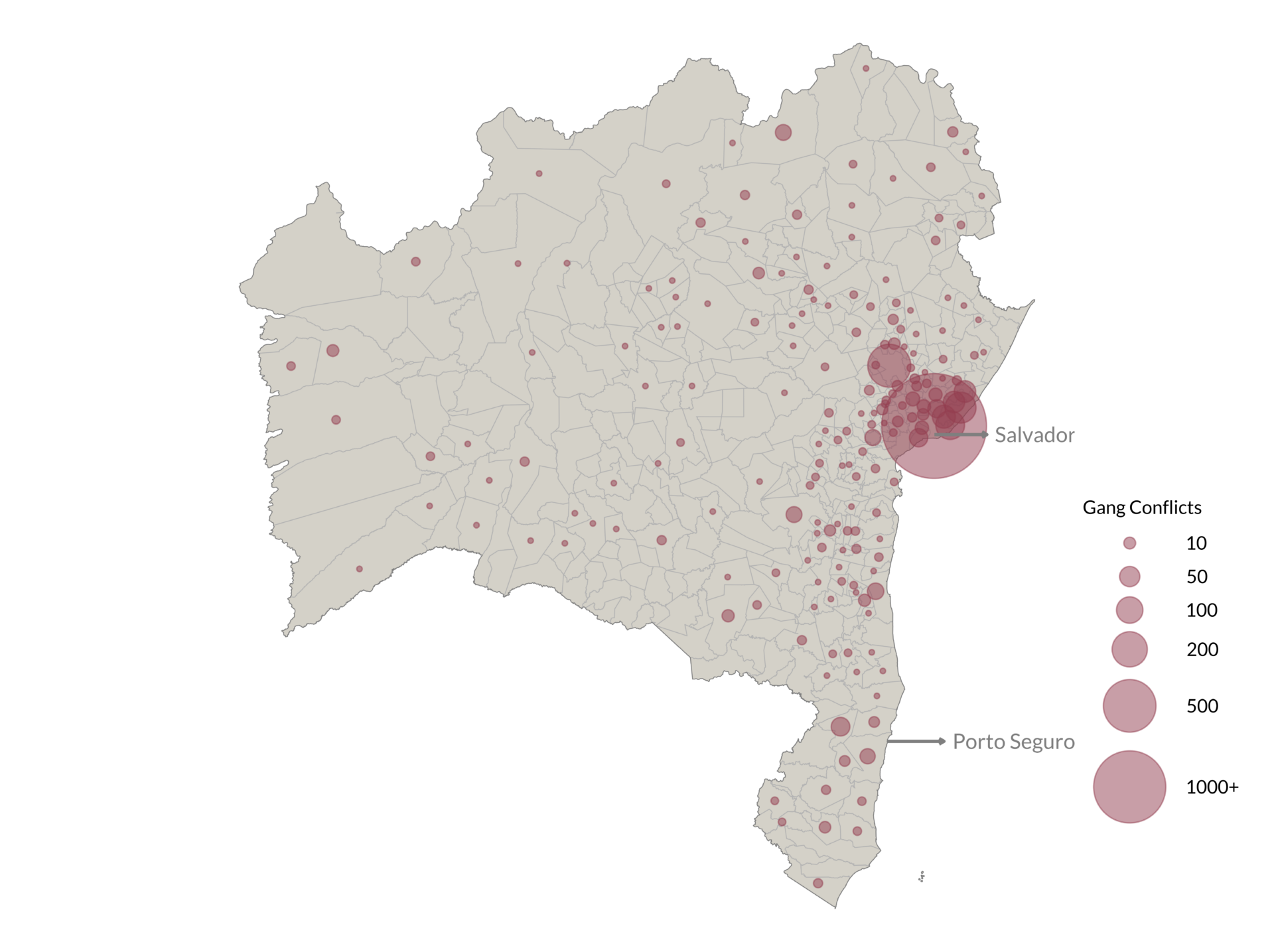

Rising criminal violence in Bahia illustrates concerning trends regarding organized crime’s capacity to shape public security in Brazil, and government responses to this violence exemplify the institutional shortfalls Brazil faces when tackling organized crime. Bahia is the fourth most populous state in Brazil, with a population of over 14 million, and its coastal capital, Salvador, is one of the country’s main hubs for drug exports to West Africa and Europe. There are 21 criminal organizations operating in Bahia – approximately 23% of the illicit entities mapped nationwide. Lethal police crackdowns have dramatically increased in tandem with the rise in criminality in the state: between 2019 and 2022, killings by police in the state doubled, reaching 1 464 victims per year.

Under the Index, Brazil ranks 18th out of 35 countries in the Americas for overall resilience indicators against organized crime (scoring 4.92 out of 10). This low resilience score is due to difficulties in implementing anti-organized crime policies at a national level. Indeed, the 2023 Index gave Brazil a score of 4.5 out of 10 for national policies and laws that can effectively combat organized crime, and the same score was given to law enforcement capacity. With state governments controlling police forces, the federal government has its hands tied and has largely been unable to coordinate effective public security solutions to rising criminality.

As evidenced by the increase in police lethality in Bahia, the response by local governments has been to allocate resources to militarized policing rather than strengthening investigative capacity. They also neglect to coordinate public security strategies or share best anti-crime practices with other states. Mafia-style groups and criminal networks have exploited this fragmented policy landscape and institutional shortcomings to expand into new territories and invest in various licit and illicit markets with minimal resistance from government institutions.

Insights from gang conflict data

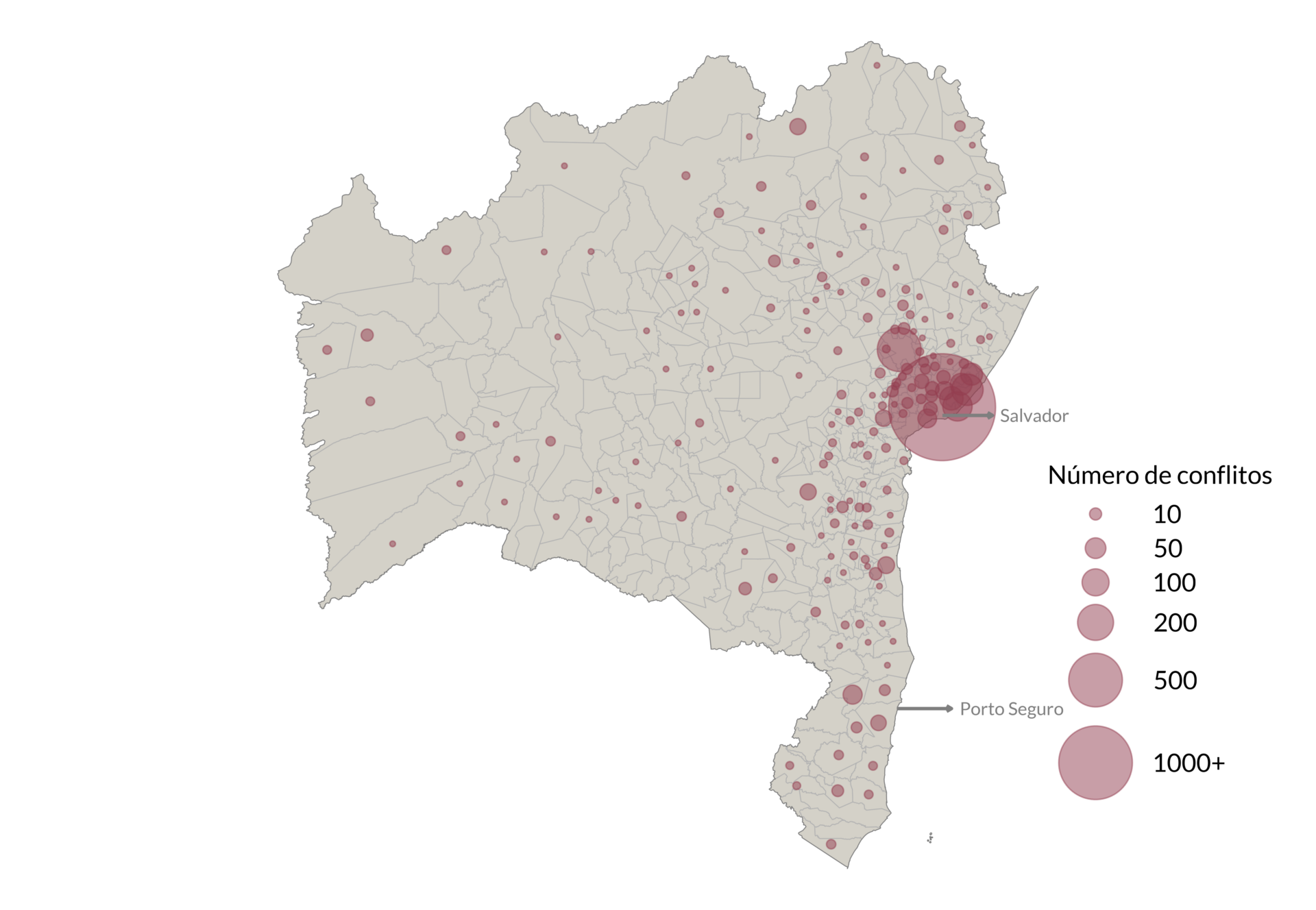

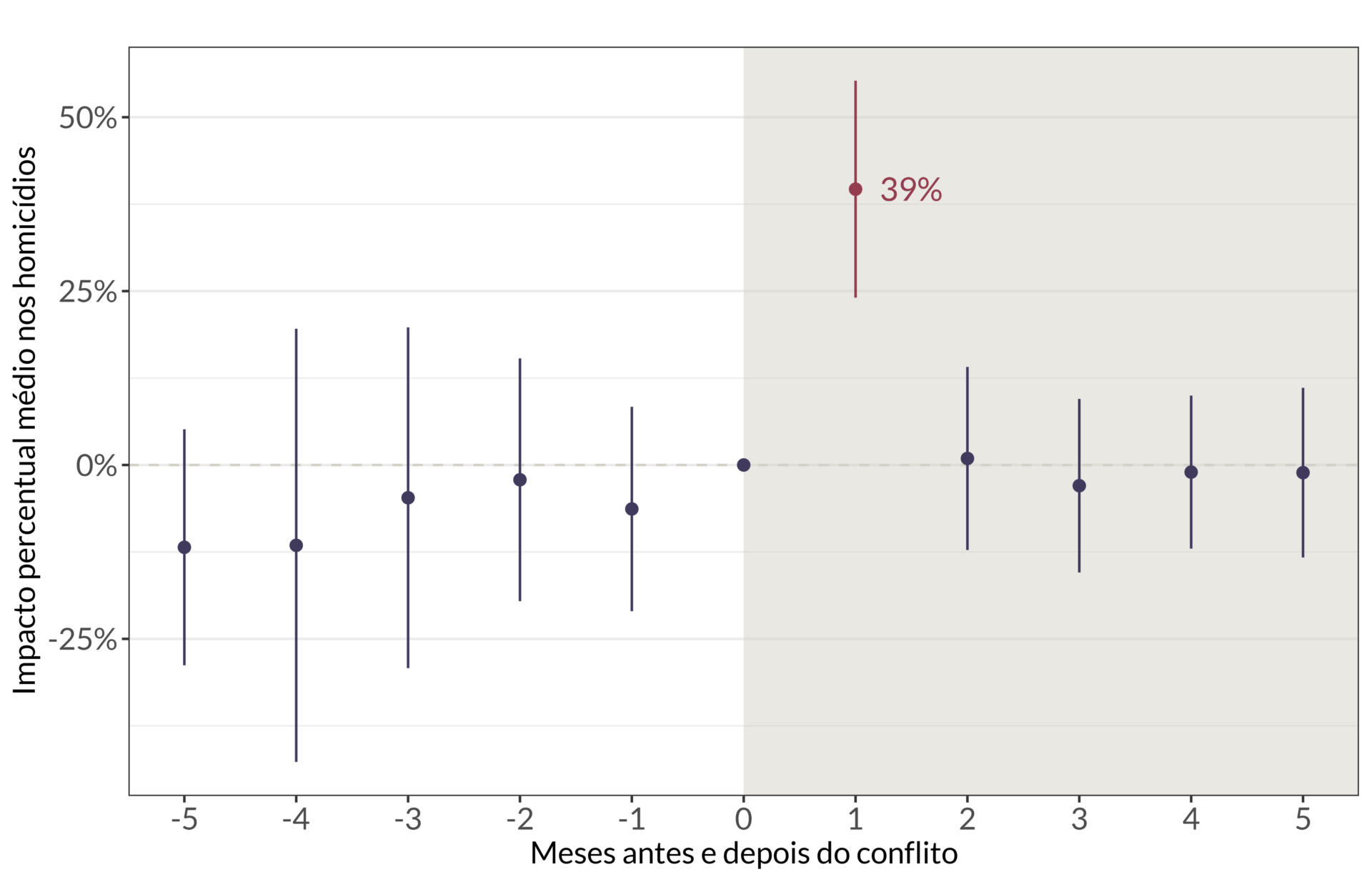

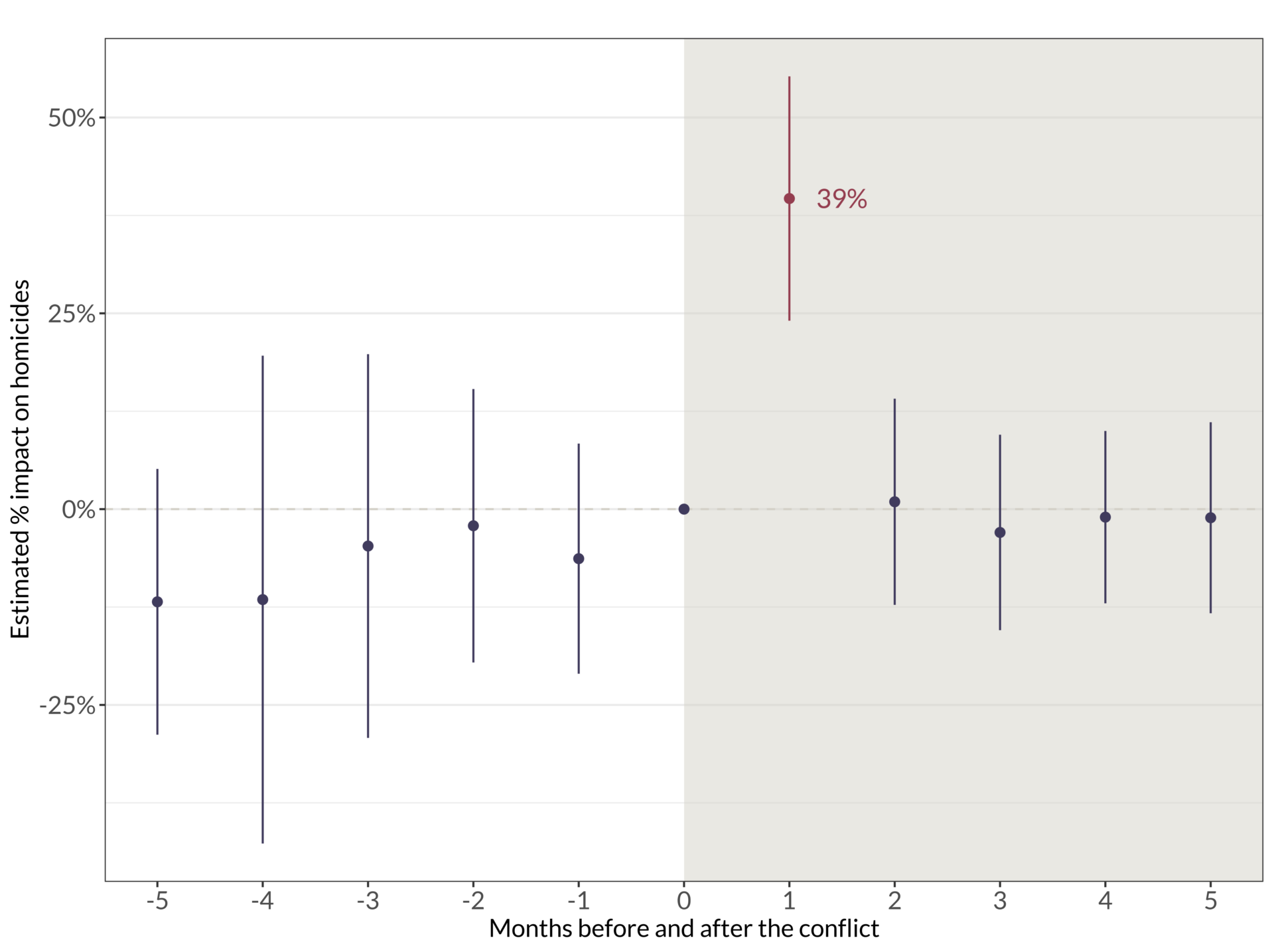

To quantify the impact of criminal networks on homicides in Bahia, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) used monthly gang conflict data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) and official homicide records from Brazil’s national health system (SUS) for the cities in Bahia for 2023. The GI-TOC also analyzed typological and spatial patterns of conflicts involving criminal networks in the state.

Between May 2022 and April 2025, more than 3 500 conflicts involving criminal networks occurred in Bahia, with 62.4% being clashes between rival groups or between criminal networks and state security forces. The remaining 37.6% were incidents in which criminal networks attacked civilians.

The statistical results show that each clash involving criminal networks led to a 39% increase in homicides in the municipality where it occurred in the month following a clash. By the second month, homicide levels returned to baseline, suggesting that the violence is concentrated around specific events involving criminal networks.

These results underscore the central role that organized crime plays in driving lethal violence in Bahia. Homicides are closely tied to these dynamics and occur in localized, time-bound clusters involving criminal actors. This highlights the need for rapid and targeted interventions to disrupt organized crime violence. Further analysis shows that the victims of the rising number of homicides caused by clashes involving criminal networks are black or of mixed-race. As a result, every increase in clashes between criminal networks has an overwhelming impact on non-white communities. Rising criminal violence is therefore exacerbating Brazil’s racialized geography of violence: generations of segregation have concentrated Afro-Brazilian communities in underserved urban outskirts where the state provides few public services and police operations are disproportionally deadly. These same territories are now the primary battlegrounds for the PCC, the CV and their local partners.

The dominant role of criminal networks in Brazil’s public security challenge is clear. By refusing federal assistance, the Bahia state government exemplified the deficiencies in Brazil’s public security sector, where each state government approaches crime and violence issues in isolation. The state government’s justification is at odds with the reality, where organized crime is greatly contributing to human insecurity. Failing to acknowledge the severity of the public security crisis benefits criminal networks and mafia-style groups, who continue to engage in violent clashes to consolidate their already powerful positions in the state.

Rather than pursuing heavy-handed confrontations without coordinating with other public security stakeholders, state governments have the opportunity to contribute to a new paradigm for Brazil’s alarmingly low resilience to organized crime. Partnering with federal government agencies, exchanging intelligence and best practices with other states and policy experts, and leveraging data on violent crime can improve law enforcement interventions. While public security policies in Brazil have suffered because of a lack of reliable data, this analysis demonstrates that there is increasingly robust statistical evidence available to guide better responses to Brazil’s extensive political economy of crime.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.