Posted on 02 Apr 2025

At a moment when long-held global alliances for peace and security are being tested, the United Nations is undergoing a wholesale review of its peace operations. In 2025, it is undertaking both a peacekeeping review and a peacebuilding architecture review. In May 2025, Germany will host a peacekeeping ministerial, a high-level forum for member states to consider the future of peacekeeping, after which the UN in New York will take up the process. The peacebuilding review is beginning an intergovernmental process this year, which should culminate in final resolutions in the UN General Assembly and Security Council this year.

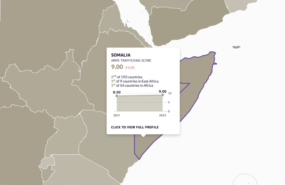

These reviews are happening at a time of dramatic ruptures in global politics, which are likely to have implications for sustainable peace. It is also a time of major changes within the UN peace agenda, with continual calls for Security Council reform, cases of countries ejecting UN peace and political missions, such as Mali and Somalia, and slashed UN budgets.

In the preparatory work for the UN peacekeeping and peacebuilding negotiations, transnational organized crime has been raised as a key risk to address. Much has been done in the past to try to counter organized crime in the context of conflict, but efforts have fallen short of meeting the challenge. This year’s focus on the future of peace operations is a timely opportunity to spark new debate within the United Nations on the crime–conflict nexus and generate ideas for more effective interventions.

This policy brief addresses the shifts underway in the UN peace operations framework, as well as geopolitically. It considers what they mean for combating transnational organized crime and identifies four key points for policymakers to consider as negotiations get underway for the peace operations architecture:

- Account for responses to organized crime across the spectrum of peace operations. As both review processes get underway, the pervasive harms to peace caused by organized crime should not be isolated to one discussion, but embedded in each.

- Move beyond past technical responses. Much has been tried and lessons learned. But the impacts of transnational organized crime extend far beyond trafficking routes. Especially in conflict settings, illicit markets expand, diversify and impact a growing geographic and societal space. The future of combating organized crime in peace operations should be strategic, networked across agendas and agile. Partnerships between the UN, regional organizations, coalitions of willing governments, civil society and local actors will be key for this.

- Make rule of law a centrepiece in the debates. Justice sector reform, accountability and rule of law are critical components of peace operations. They are also critical for combating criminal networks. Downplaying these components would signal a retreat from holistic responses to crime and conflict, and an opening for criminal opportunists.

- Resilience to crime is resilience to conflict. Include a reference in the peacebuilding architecture review outcome document that recognizes the challenge to peace caused by transnational organized crime and that efforts to reduce the harms caused by organized crime help build peace.