Posted on 09 Dec 2020

This briefing explores the issues being negotiated before the 14th UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. The GI-TOC has seen a draft of the congress declaration, and here we summarize the member state positions and assess key issues that are missing from the draft declaration.

Background

The UN General Assembly (UNGA) has decided that the 14th UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice will take place from 7 to 12 March 2021, following its COVID-19-related postponement from the original dates in April 2020.[1] The Congress will take place in a ‘hybrid’ format (combining in-person and online), with Kyoto still nominally the host city. The primary purpose of the Congress is to act as a ‘forum for exchange[2]’ between governments, international organizations and civil society on crime prevention and criminal justice issues.

Since the first quinquennial Congress in 1955, the Congress has promulgated a wide range of recommendations, resolutions, and standards and norms (soft law) on crime-prevention issues, including the Standard Minimum Rules on the Treatment of Prisoners (known as the Nelson Mandela Rules). In addition, since the last time the Crime Congress met in Kyoto (in 1970), it has usually adopted an outcome document in the form of a political declaration.

Taken together, the outcomes of the Congresses have been instrumental in the development of legally binding instruments, such as the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) and the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), and in the creation of the UN Crime Programme and the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ), the UN Economic and Social Council body to which the Congress is now a consultative body.

The political declarations

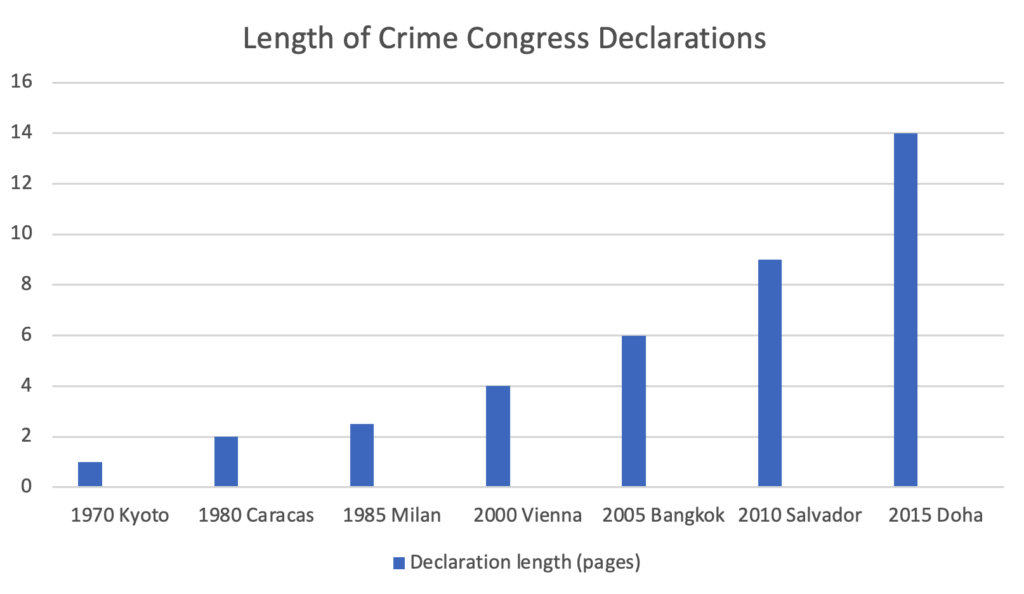

Congresses adopted occasional declarations in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and this became regular and formalized in 2000. The first Congress declaration, adopted in 1970 in Kyoto, was short and concise. In 1980, the Caracas Declaration was two pages long, and was followed by the two and a half pages of the ‘Milan Plan of Action’ in 1985. No declaration was adopted in the 1990 Havana or 1995 Cairo Congresses, but since the turn of the millennium each Congress has produced a single political declaration, starting with the Vienna Declaration on Crime and Justice in 2000, which ran to four pages. According to the 2002 UNGA resolution setting out the updated role and format of the Congress, the Congress ‘shall adopt a single declaration containing recommendations derived from the deliberations of the high-level segment, the round tables and the workshops, to be submitted to the Commission for its consideration’.[3] The Bangkok Declaration of 2005 stretched to just over six pages; the 2010 Salvador Declaration reached nine pages. The Doha Declaration of 2015 is the longest so far adopted, with 14 pages. Importantly, it was also negotiated and provisionally adopted in Vienna before the Congress actually took place, making it impossible to reflect the discussions and deliberations at the Congress itself (as intended by the UNGA resolution 56/119). The Japanese hosts in 2021 have opted for the same model, hoping for the Declaration to be adopted before the Congress.

The draft declaration is currently being negotiated in Vienna by the diplomatic missions attached to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which organizes the Congress along with the host country. The latest text distributed to missions in Vienna has 22 pages (including track changes and comments), along with five pages of suggested new paragraphs submitted by member states.

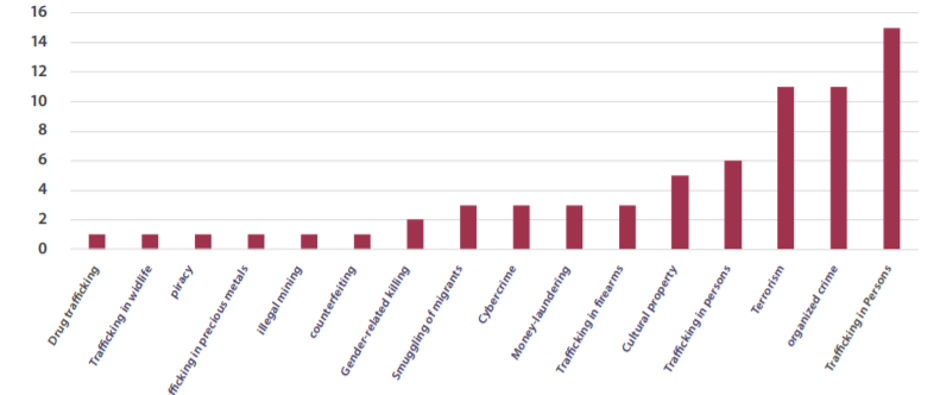

The growing length of the documents reflects how the range of issues discussed by the Congresses has grown over time. Our analysis in ‘The Road to Kyoto’ showed that the range of crime types mentioned in the Doha Declaration in 2015 was very broad (see the graph below):

We also demonstrated that the declarations since 2005 have had an increasing impact on policy discussed and adopted at the CCPCJ, but that there is an ongoing dissonance between priority issues of the Congress, what is included in the declaration and what the realities are in the outside world. For example, Qatar’s priorities were education, the rule of law and the SDGs, but the declaration ended up focusing heavily on trafficking in persons. And the big migration crisis of 2015 was skirted around with only a few references to the smuggling of migrants.

The Japanese hosts want to focus on the rule of law and Agenda 2030, reflected in the current title: ‘Kyoto Declaration on Advancing Crime Prevention, Criminal Justice and the Rule of Law: towards the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. Linked to this is the priority of continuing to highlight the importance of a ‘culture of lawfulness’, which was agreed to in the Doha Declaration. This concept is one of the issues that is up for debate in the current negotiations, and much of the document is still not agreed. States have yet to agree on a number of theoretical issues (e.g. how to reflect the current nature of crime, the impact of COVID-19, the ongoing influence of technology and globalization, which parts of society should be included in responses, and the importance of human rights in criminal-justice responses), and on how to reflect and respond to a number of illicit markets and the links between them. Cybercrime, environmental crime and terrorism are particularly contentious in the negotiations. In addition, there are various disagreements over state responses to organized crime through prevention and criminal-justice policies – for example on gender issues, protection of journalists, working with communities, rights of prisoners and the proportionality of sentencing.

Despite the broad range of issues included so far in the agenda, whether agreed to or not, there are a number of major and fundamental issues related to the current nature of organized crime and the responses that are missing. There are also several glaring gaps that the GI-TOC believes should be included and has suggested proposed wording. The summary and analysis that follow reflect the positions and proposals contained in that draft.

Areas of agreement

With less than three months to go until the Congress, and with the caveat that ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’, what does the current draft declaration count as ‘agreed’? Member states have agreed on a range of general priorities and specific commitments and recommendations. But these commitments are by nature fairly uncontentious: expressing support for the rule of law and the role of the UN; and expressing support for approaches such as prevention, youth empowerment, agreed frameworks of prisoner rights and international cooperation on criminal matters. Nevertheless, it should be welcomed that there is broad agreement from the outset on these issues, which are summarized below:

-

Crime prevention and criminal-justice issues need to be better integrated into the wider UN system.

-

The rule of law should be promoted, international cooperation in criminal matters should be promoted, capacity building on law-enforcement on criminal justice is needed.

-

The CCPCJ is the prime policymaking body of the UN on these issues.

-

Evidence-based crime-prevention strategies are important.

-

Youth should be empowered to be agents of positive change in their communities.

-

Victim support in criminal proceedings should be provided; witness protection should be provided.

-

The Nelson Mandela Rules for the treatment of prisoners should be promoted; rehabilitation should be provided in prisons and in the community; reintegration strategies should be delivered.

-

Anti-corruption strategies should implemented.

-

Central authorities should be supported to carry out international cooperation activities.

-

Exchange information, including through INTERPOL.

-

Effectively and efficiently manage and dispose of confiscated assets.

-

Share information on beneficial ownership.

-

Improve the security and resilience of critical infrastructure.

Areas of disagreement

However, it is striking that there remain more numerous areas of disagreement in the draft text. Although it is not unusual to find dissonance in negotiations of this kind, it is unusual that there are fundamental issues on which there is not yet consensus. These range from understanding threats and challenges to agreeing on recommendations or calls to action on certain issues. The status of these disagreements is summarised below.

The nature of crime, cyber and human rights

A paragraph on the nature of crime has become hostage to polarized debates on cybercrime. The paragraph expresses concern that crime is ‘becoming increasingly transnational, organized and complex, thus creating unprecedented challenges … .’ However, India has proposed adding an extra adjective – ‘online’ and is supported by others in seeking to emphasize cyber elements in this paragraph, which is opposed by Russia and others from their ‘like-minded’ group on cyber issues, who are seeking to bolster language on new approaches to cyber elsewhere in the document.

There is also a bone of contention in how the declaration encourages member states to use technology to fight crime. Western countries have teamed up with Mexico and Honduras to insist that a commitment to use technological tools comes with a commitment to respect for human rights in doing so. This is being resisted by Iran, China, Guatemala, Venezuela, Egypt, Russia, Syria, Malaysia, South Africa, Cuba, Singapore and Nigeria.

Multi-stakeholder partnerships

A paragraph committing parties to multi-stakeholder partnerships to prevent and combat crime is also being fought over. References to civil society, academia and the scientific community, and local communities are being opposed by Syria, who are supported by Turkey in opposing engagement with local communities specifically. Nigeria, the UK, Canada, Japan and Russia, however, are supporting the reference to local community engagement. China, Iran and Syria are also opposing the use of the term ‘multi-stakeholder’. Iran and Russia are proposing that this type of partnership should take place only ‘in accordance with national law’. Those supporting strong references to multi-stakeholder partnerships and non-governmental groups are Norway, Canada, Finland, Japan, Honduras and Sweden.

COVID-19 and crime

There is also disagreement on how the declaration should refer to the effects of the pandemic on crime. Although there is general agreement that the pandemic has created opportunities for organized crime, there is little consensus on how this should be described, or on whether criminal markets should be singled out. Iran, Russia, Syria and Indonesia favour a short paragraph without details on criminal markets, but Norway is one country favouring a list of crime types to be identified. Countries including Liechtenstein, Belgium, Honduras and Israel want to emphasize trafficking in persons and the smuggling of migrants; Argentina, Honduras and Guatemala want to emphasis gender-based violence. References to criminal-justice facility responses are also proposed in the draft, but opposed by some: Brazil, Israel, Armenia and Indonesia in particular object to references to overcrowded prisons, which is being promoted as an issue by Norway and Japan. A subsequent paragraph on how the multilateral system should respond to COVID on crime issues is equally muddled at this stage.

Human rights, sovereignty and the principle of non-intervention

Disagreements have also been laid bare in terms of how to refer to human rights, and linked to that how to refer to sovereignty and the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states. Stronger references to human rights and proportionality of sentencing are being proposed by Western countries, while references to proportional sentencing are being opposed or caveated by Iran, Singapore, Egypt and China. A broad group of countries prefer to stick to the original weaker text on human rights – including Turkey, South Africa, Morocco, USA, Guatemala and Indonesia. In light of its views on UN sanctions, unsurprisingly Iran is attempting to edit a paragraph on upholding the Charter of the UN, and its principles on sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs. In particular, it is seeking to water down a commitment to upholding the UN Charter and inserting the phrase ‘sovereign equality’ alongside sovereignty. France is also advocating to delete a reference to the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states, which has been opposed by Argentina, Egypt and China. The broad and cross-regional majority are seeking to retain the original text on these issues, which is based on previous consensual text included in the 2015 Doha Declaration.

There follows a list of actions that the signatories to the declaration ‘endeavour to take’. Iran has put a reservation on this, meaning that even this fundamental concept of how to follow up the declaration is not yet agreed to.

Root causes of crime and risk factors

There is a debate over the emphasis that should be placed on root causes in addressing crime prevention. China and Iran wish to downplay the prominence of root causes, and Brazil wishes to delete a reference to ‘risk factors’. There is a broad consensus among countries, however, that are in favour of emphasizing both root causes and risk factors – mainly Western countries along with the Philippines, Honduras, Mexico, Honduras and Nigeria.

Economic dimensions of crime

There is a paragraph devoted to addressing the economic dimensions of crime (as addressed in the recent UNTOC COP resolution of October 2020 tabled by Italy.[4]) Although there are relatively minor differences of emphasis on how to address financial crimes, illicit flows and money laundering, there are more major differences on the issue of asset recovery. Argentina, Nigeria and China are arguing for more specific emphasis on asset recovery; the US, Liechtenstein and Switzerland argue for more emphasis on measures to address money laundering.

Community engagement and the culture of lawfulness

A paragraph on ‘community-based’ strategies is facing debates over terminology and emphasis. Turkey is opposed to referencing ‘community’ and favours instead referring to the ‘social perspective’. A large number of member states, including Iran, China and Mexico, are more comfortable talking about ‘community’ engagement. The ‘culture of lawfulness’ is a priority for the Japanese congress hosts and has been referenced since the 2015 Doha Declaration. However, Russia, Iran and Egypt are proposing to delete this concept, in favour of the ‘rule of law’. Subsequent references to community engagement are being caveated by China to ensure that any engagement includes the police and law enforcement, and with a view to building trust towards public institutions, while Turkey opposes references to ‘community’ throughout.

Gender perspective, gender equality and gender-related violence

Mainstreaming gender perspectives into programming has become a familiar topic in the policymaking bodies in Vienna, and there has been agreed language in recent resolutions and declarations on this, including in the Doha Declaration. However, Iran and China are opposing references to gender equality, and Iran is opposing references to gender-related violence, which are supported by a group of Nordic and Latin American countries. The UK, Canada and Israel are also promoting the advancement of women and gender diversity in law-enforcement and criminal-justice institutions. This is being resisted by Iran and China. On criminal-justice proceedings, Iran and Russia are opposing language on gender-responsive measures being an ‘integral part of criminal justice strategies’. Language on the rights of women and girls – proposed by Canada, Colombia, Honduras, SA, Turkey, UK, Israel, France, Japan and Argentina – is being opposed by Iran. In a section on access to justice, Canada and Sweden have proposed a commitment to listing types of racism and discrimination to be avoided in justice systems – including on sexual orientation, religious beliefs, xenophobia and gender. This is opposed by Russia and Algeria.

Youth justice

South Africa is proposing replacing references to ‘juvenile justice’, with ‘children in conflict with the law’, and is supported in this by the US. The UK and China are opposing this language, with the UK more comfortable referring to juvenile cases or offenders, and China with ‘cases committed by children’ or ‘children who break the criminal law’.

Victim protection

China is opposed to endorsing a ‘victim-centred approach’, preferring to caveat commitments to supporting victims with references to domestic law.

Prisoner transfer

China and Iran are attempting to water down a section promoting measures to enable prisoners to serve sentences in their own countries.

Restorative Justice

Canada, South Africa and Colombia are promoting strong language supporting restorative justice as part of criminal-justice systems. These references are being opposed or watered down by China, Iran and Russia.

Safety of journalists

A commitment to ending impunity for crimes against journalists and media workers is being opposed by Egypt, Iran and China.

Terrorism and organized crime

Iran is leading the charge in attempting to weaken commitments to implement the international counter-terrorism instruments and opposing references to countering terrorist financing – proposed by Iraq and Israel. Iran is also opposing references to the Financial Action Task Force, along with Venezuela, Pakistan and Nigeria. The links between terrorism and various other types of crime are still being debated, with issues linked to drug trafficking, cryptocurrencies, kidnapping and hostage taking all being promoted by some member states. Germany is advocating sticking to generic language on the issue. How to treat foreign terrorist fighters is also not agreed to: Turkey, Azerbaijan, Iran and Iraq advocate return or extradition to countries of origin.

New, emerging and evolving forms of crime

The area of new and emerging crimes is a traditional battleground for countries promoting agendas on specific crime types, and this current negotiation is no different, with various new and emerging issues being suggested – and objected to. New proposals to include in a listing exercise are trafficking in genetic resources, proposed by Iran; illegal waste handling (proposed by Sweden, Spain, Italy and Norway); illegal dumping (Kenya); illicit trafficking in hazardous waste (Canada); push-back of migrants (Turkey); trafficking in persons (Liechtenstein, Israel, Spain, Canada, Guatemala and Philippines); drugs and firearms (Japan); smuggling of migrants (Italy). Among the list of crimes included in the text, objections have been raised against the following: crimes that affect the environment (Iran); counterfeit goods (India, Brazil, China, Thailand and Iran); falsified medical products (Iran); smuggling of commercial goods (Iran, Venezuela).

Cybercrime, tech against crime

Cybercrime has its own dedicated paragraph, with the usual Western-G77/Russia split in priorities. Western countries are promoting the use of international cooperation provisions and safeguarding human rights in the fight against cybercrime, while promoting the role of the CCPCJ and its Intergovernmental Expert Group on cybercrime. Russia leads a group of countries (Venezuela, South Africa, Iran, Azerbaijan, Syria, Palestine, China and Iraq) referencing the upcoming ad hoc committee to elaborate a convention on cybercrime, and with more focus on updating legislation and the international legal framework. China, Russia, and Iran are opposing human-rights language in this context as well.

Regarding the use of new technologies as counter-crime tools, there is general agreement on the need to use technological developments by law enforcement and criminal-justice institutions, but disagreements prevail over human rights and data-protection issues.

What is missing from the draft declaration?

There are a number of so-called ‘additional paragraphs’ that have not been included in the text, but have been tabled, including the following thematic areas and issues:

-

The vulnerability of prisoners during the pandemic (supported by a wide group, but tabled by South Africa and pending further discussion at the request of China).

-

Safeguarding multilateralism to prevent and counter crime, and support the rule of law (supported by a wide group and tabled by China but questioned by the US).

-

The importance of and responses to child sexual exploitation – proposed by Australia and questioned by Iran, Russia and China.

-

Safety of journalists – proposed by Canada and questioned by Iran and Russia.

-

Proportionality of sentencing – proposed by France and questioned by Singapore and Iran.

-

A commitment ‘to prevent, prosecute and punish all forms of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and end impunity in this regard’ – proposed by Denmark, but questioned by Singapore and Iran.

-

Strengthening implementation of international anti-corruption architecture – proposed by Australia, but questioned by a broad group.

-

Mexico have proposed two paragraphs highlighting efforts to counter trafficking in firearms, questioned by Iran, China and Singapore.

-

Technical assistance for developing countries is highlighted in a proposal from Iran, but opposed by France, Canada and the US.

-

Iran has also proposed a paragraph on refraining from sanctions (‘Unilateral Coercive Measures’) – supported in principle by Russia, but opposed by the US.

-

France has tabled a proposal on prioritising measures against foreign terrorist fighters, which is questioned by Iran, Russia and Turkey.

-

France has tabled a proposal on drug trafficking, in line with the UN General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem 2016, which is questioned by Russia and Iran.

-

France has also tabled proposals on human trafficking, human smuggling and firearms trafficking – in line with the three UNTOC protocols. In addition, France has tabled a longer paragraph on environmental crime, listing various types of crime that affect the environment, and recommending multi-faceted cooperation to address it. It is supported by European countries and Kenya. However, it faces strong opposition from Brazil, Argentina and Iran.

-

The UK and Armenia have tabled proposals on addressing hate crimes. The British proposal includes references to discrimination based on sexual orientation, which, predictably, is opposed by Iran.

-

Belgium has proposed a paragraph on falsified medical products, which is opposed by Brazil, Iran and India.

-

Egypt has proposed by a paragraph on trafficking in cultural property, which is opposed by Brazil.

This spectrum of thematic issues and proposals confirms that the Kyoto Declaration will follow in the footsteps of the Doha Declaration and address a commendably wide range of issues regarding crime prevention, criminal justice and organized crime. However, from the perspective of global civil society interested in addressing and mitigating the effects of transnational organized crime, the GI-TOC believes there are major additional gaps in the declaration, and we call on member states to address these. The areas where we believe the draft declaration falls short are set out below.

Strategic picture of organized crime, and links to conflict and governance

Although the declaration will address the transnational nature of crime, it should do more to reflect how recent years have seen monumental changes in how the world works – technological innovation, international terrorism, financial crises, globalization, a decline in multilateralism, and now the unprecedented crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. This declaration is an opportunity to address the scale and importance of these issues. Despite the growing evidence of illicit markets as enablers of conflict, and the prevalence of organized crime as an issue at the UN Security Council, in the current draft there is no reference to organized crime as a driver of conflict. Equally, there is no call to action to address the nexus of corruption between business, criminals and state figures – an interconnectedness that allows organized crime to thrive.

The first Kyoto Declaration in 1970, though short, recognized the urgent scale of the problem. As it stated, ‘… the problem of crime in many countries in its new dimensions is far more serious now that at any other time in the long history of these Congresses’.[5]

It added that there was ‘an inescapable obligation to alert the world to the serious consequences for society of the insufficient attention which is now being given to measures of crime prevention …’

Organized crime has adapted, evolved and thrived in the subsequent 50 years. This congress has an opportunity to make a similarly bold and emphatic statement to reflect the current situation, which is already partly reflected in the opening section of the current draft, but we would suggest adding some elements to demonstrate the harms of organized crime. Our proposed wording is as follows:

Despite our common efforts, organized crime continues to thrive in all of our countries. We recognize that organized crime fuels conflict, undermines the rule of law, enables corruption, holds back achievement of the SDGs, degrades the environment, violates human rights, harms communities and breeds violence. Further, we recognize that organized crime continues to evolve and adapt to changes in society and capitalize on crises, as we have seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. We resolve to adapt and evolve our responses to organized crime and underline the unprecedented urgency and importance of these efforts.

Gangs and urban security

There is not yet any agreement on how to reflect urban crime and gangs in the current document. The Doha Declaration settled on calling for more research on urban crime and gangs, and their links with other manifestations of organized crime. This is an issue that deserves more attention, as it is predicted that, by 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas. In addition, urban crime continues to proliferate around the world, resulting in increased violence and criminal control over local communities. Failure to understand and deal with urban crime in this declaration would be a failure to address the inequality and violence that is bred by urban crime and gangs. We recommend that in addressing urban crime, it is imperative to make reference to Agenda 2030, and the New Urban Agenda adopted at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in Quito, Ecuador, in October 2016.

Assassinations

In May 1992, Giovanni Falcone, the courageous anti-mafia judge was murdered by organized crime in his home city of Palermo, only one month after representing Italy at the first ever UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in Vienna. His assassination spurred on those determined to create the UNTOC. When the convention was adopted in 2000, the commitment of the international community to tackling this threat was loud and clear.

However, the Convention, and our wider efforts, has not stopped the violence of organized crime. Through the work of the GI-TOC, we know that thousands of people have been deliberately assassinated by organized criminal groups. Earlier this year, a senior police detective, Charl Kinnear, was shot dead outside his home in Cape Town. Kinnear was working on several high-profile investigations into organized crime. The tragedies of Falcone and Kinnear are not isolated cases. Increasingly, criminal groups around the world are targeting those whom we can broadly categorize as civil society. Such individuals are targeted because they confront and challenge the power, authority and local dominance of criminal interests the world over. In recent years, lawyer Dirk Wiersum was gunned down in the Amsterdam. Journalists Jan Kuciak, Daphne Caruana Galizia, and Javier Valdez have been killed. The list, tragically, goes on, and on.

Therefore, we recommend including the following paragraph in the declaration:[6]

Commemorating all victims of organized crime, including those who have lost their lives fighting such crime – including law enforcement and judicial personnel, journalists and individuals from civil society who have been targeted for standing up to organized crime. Their legacy lives on through our global commitments to preventing and combating organized crime.

Trauma and costs for local communities, and the need for their involvement in responses

There is not yet agreement in the draft document on how to involve communities in responses to organized crime or in criminal-justice responses. A first step must be to recognize the harm and trauma caused to local communities by organized crime, and then to commit to including community members affected in the developing responses to organized crime. We recommend incorporating the following text:

We recognize that organized crime has global, national and local detrimental effects. As a result of organized crime, communities around the world face violence, poverty, lack of service provision and diversion of public funds. Communities must therefore always be actively involved in the development and implementation of crime prevention and criminal justice policies. Their involvement will help increase trust in public institutions, safeguard human rights, ensure sustainability of responses – and ultimately build a culture of lawfulness and peace, in place of criminality.

[1] UN General Assembly, Fourteenth United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, 6 August 2020, https://undocs.org/A/74/L.80.

[2] UNGA resolution A/RES/46/152 outlines the current mandate of the Congress. It stipulates the following: ‘The United Nations congresses on the prevention of crime and the treatment of offenders, as a consultative body of the [crime] programme, shall provide a forum for:

-

The exchange of views between States, intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations and individual experts representing various professions and disciplines;

-

The exchange of experiences in research, law and policy development;

-

The identification of emerging trends and issues in crime prevention and criminal justice;

-

The provision of advice and comments to the CCPCJ on selected matters submitted to it by the commissions;

-

The admission of suggestions, for the consideration of the commission, regarding possible subjects for the programme of work.’