Posted on 07 Dec 2017

This paper is based on a detailed review of the scale and nature of organised crime’s infiltration of the private sector. These findings are a ‘call to arms’ for the international private and public sectors to transform their co-operation and teamwork.

We have adopted a practical definition of organized crime as that which is carried out by a group of people, suspected of serious criminal offences, over a prolonged period, motivated by profit or power. In our analysis of six major private sector industries, six specific forms of organised crime stood out as either having material impact on the private sector or using the private sector as facilitators.

Money laundering is the process of making dirty money look clean. One estimate puts it at 2% of global GDP – c.$1.5 trillion. Money-laundering is an ‘enabling crime’, facilitating organized crime (as well as terrorism) with social and economic costs.

Asset misappropriation refers to stealing from businesses. For example, cargo thefts cost as much as $30 billion in losses each year worldwide.

Counterfeiting and contraband, whilst thought of as being a consumer goods crime, is rife in a broad range of sectors, in particular, technology products and pharmaceuticals, to devastating effect. It is estimated by OECD at $461billion, or 2.5% of world trade.

Fraud and extortion remain strongly present in the financial, construction and real estate industries. In construction, extortion could account for of 20–30 percent of lost project value.

Human trafficking. High volume, low skilled labour enterprises such as construction and building, have the highest penetration of trafficking incidence in the private sector.

Cyber Crime. Hacking attacks cost the average American firm $15.4 million per year over. In 2015 68,000 URLs containing child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA) images were hosted online on 1,991 domains. The reputational impact means major tech companies apply significant collaborative resources to weeding out criminal, terrorist and CSEA activity.

Key Findings:

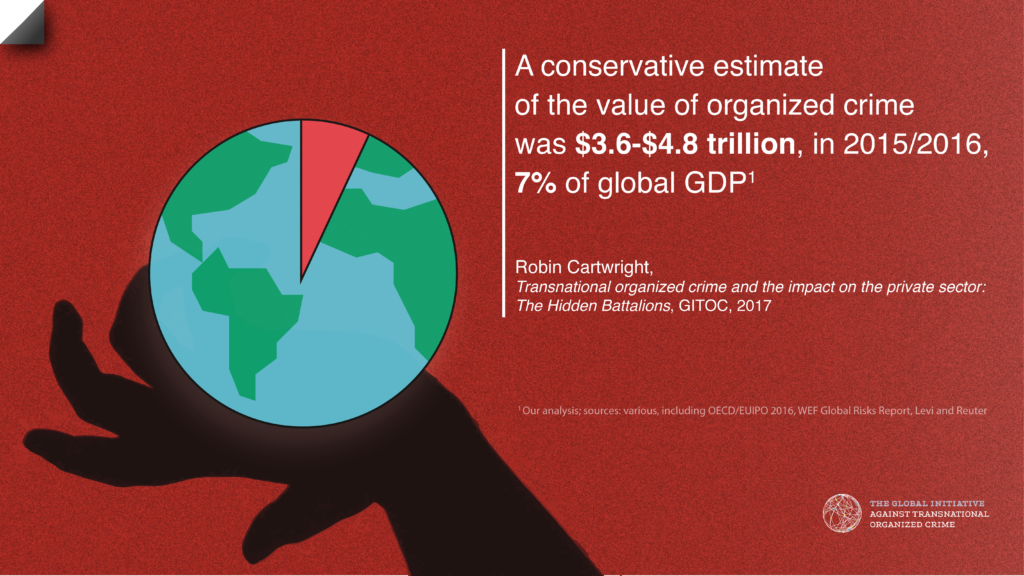

Finding#1: The scale and impact of crime in the private sector is truly staggering. A conservative estimate of the value of organized crime was $3.6-$4.8 trillion, in 2015/2016, 7% of global GDP. The broader impact of organized crime is difficult to assess as it is multi-dimensional, and shared across the private, public sector, and society itself. The impact on the private sector only – in terms of revenue loss – is estimated at c$130 billion.

The Institute of Economics and Peace (IEP) calculated the financial cost of terrorism at over $52 billion in 2014. A conservative estimate of total transnational organized crime is $870 billion a year. This is more than six times the amount of official development assistance and close to 7% of the world’s exports of merchandise

Finding #2 Private sectors are either facilitators or targets. Crimes are either done ‘to’ private sector organisations, or ‘through’ them. Sectors are either the targets of fraud or asset theft themselves, particularly in construction, consumer goods ($460 billion counterfeit goods), and financial card fraud or they facilitate crime unwittingly, through use of technology networks by fraudsters to target victims, e.g. the real estate sector laundering dirty funds or the transport industry moving illicit goods.

Regulation varies between the ‘victim’ and ‘enabling’ industries. Laws are in place to criminalise the use of the private sector for technology or money laundering crime. The victim industries, however, often are reliant on existing laws around theft, or copyright infringement, which are not tailored to the activities of TOC groups and tend to have lower penalties for infringement.

Finding #3 Organized crime’s impact on the private sector is growing not shrinking. Counterfeit goods have risen from $250 billion to $461 billion in the last 8 years. Asset theft in the transport and logistics theft rose by over 90% 2015 to 2016. There is a sense that regulation is not working: money laundering seizures equated to 0.2% of all laundered funds in one study; and after the dark web’s Silk Road was taken down, many sites sprung up to take on and indeed grow the trade.

Finding #4 Direct impact of crime disproportionately felt in the Global South. Sweatshops flourish in South Asia; trafficking of labour and sex workers originates predominantly in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe; corruption in natural resources damages production in Africa and the Caucasus; technology fraud is driven from eastern and southern Europe, West Africa and the Middle East. Whereas in developed economies counterfeit drugs may comprise less than 0.2 percent of the market developing markets are often beset by 30% fakes, as a UNODC report showed for anti-malarial drugs in Africa.

Globalization is increasing the ‘attack surface’ for TOC groups. The abuse of the often weaker regulatory regimes in the Global South by TOC groups further increases the risk for the private sector operating in these areas.

Finding #5 Responses are confrontational rather than collaborative. There are very few examples of successful public and private sector co-operation against TOC groups. Private sector organisations complain that communication with the law enforcement sector is one-way and that the regulatory reporting burden, designed to combat crime, can act as a deterrent to co-operation. Tangible results have been seen when industries take the lead on disrupting the work of TOC groups, such as TAPA the Transported Asset Protection Association

We recommend a concerted effort to measure and communicate the incidence of organised crime that examines the full spectrum of private sector incidence and cost form organised crime.

Public/Private sector co-operation should be kick-started by a series of sector-specific joint events, attended by regulators, law enforcers and the private sector to identify the potential for further co-operation. Following sector-specific strategies, we recommend a cross-sector dialogue is pursued to enable learning from alternative approaches, along key themes. Industry bodies should do more to offer leadership and innovation in combatting organised crime in their supply chains We recommend a cross-industry dialogue to establish ‘test cases’ for systemic supply chain protection using technologies such as product level track and trace, authentication marking and labelling, and accreditation/verification of supply chain participation.