Event Details

Where

Paris

Posted on 13 May 2016

Executive Summary

On 13 May, the GIFF Project held an International Dialogue on links between artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) and illicit financial flows (IFFs). The event furthered the GIFF Project’s work to raise awareness of IFFs linked to ASGM, increase knowledge on the topic and strengthen responses.

Key Themes and Takeaways included:

- IFFs impede formalisation. The dialogue confirmed IFFs are a concern for a wide range of stakeholders. Multiple participants, from various fields, disciplines, and geographic regions, gave concrete examples of how IFFs were a direct obstacle to efforts to formalise ASGM.

- Holistic approaches are needed. ASGM does not happen in a vacuum and is a nuanced topic. To adopt narrow definitions (informal, illegal, etc.), lenses, approaches, or partnerships puts responses at risk of being ineffective or damaging to development efforts. Widening how we define and perceive the issue of IFFs in ASM (not only development or crime) and engaging with a range of stakeholder groups is essential.

- ASGM is a livelihood. Artisanal gold mining is often poverty driven, is a lifeline for vulnerable groups, and can contribute to resilience in rural households and economic development for communities.

- ASGM is a business. The high-profit, low-risk nature of gold trading makes it appealing to organised criminal actors who exploit the sector for financial or political gain. The nature of their engagement structures a landscape where human rights violations (e.g. forced labour, child labour, health and safety issues, violence etc.) are more likely. If incentives and pathways towards more formal and legitimate business are not developed for the ASGM sector, criminal actors will continue to take advantage of the sector being marginalised and ‘beyond the pale’ to satisfy their own ends.

- Better data. There is a lack of data and a strong call for higher quality research. It is widely acknowledged IFFs are a challenge to formalisation, but more information is needed to better understand how and to develop effective responses. Minerals traceability is important, but not the silver bullet for IFFs. We must follow the money as well as the mineral. Data should not be limited to mapping IFFs, but examine motivations and vested interests in the sector. Engaging local partners is key: they are often best situated to collect data, contextualise it, and put it to use.

- Next step: The GIFF Project Toolkit. The GIFF Project has agreed to focus the Toolkit on data collection and analysis. The Dialogue highlighted this as a pressing need and offered concrete measures and techniques on how to do so.

The Dialogue was conducted under Chatham House Rule. Some phrases, ideas, or quotes are included herein exactly, or nearly, as a participant contributed it. This report should be seen as the collaborative work product of all attendees to the event, even where quotation marks aren’t employed.

Dialogue Structure and Objectives

Fifty individuals representing industry, governments, civil society, multilateral institutions, and international organisations attended. The event included presentations by panellists, sidebar conversations, a large-group discussion, and question and answer sessions throughout.

The primary objectives were to:

- Build awareness of IFFs and the role of criminal networks in gold supply chains;

- Build understanding of the extent and ways in which IFFs impede ASGM formalisation;

- Provide a platform to present practices and strategies for restricting IFFs in gold supply chains and develop strategies and initiatives to implement going forward;

- Solicit inputs for tools and strategies to identify and combat IFFs, in particular to facilitate ASGM formalisation.

Recommended tools included:

- Typology of IFFs, explaining different IFF types, how the sector generates IFFs and ‘cleans’ them.

- Tools for capacity building of agents to map, monitor, mitigate, and report on IFFs. This includes enabling stakeholders to examine ASGM through a financial lens and to map financial flows (both licit and illicit). In particular, mapping and understanding choke points and hubs. Tools may include frameworks, questionnaires, and lenses through which to understand financial relationships at local communities and mine sites. Specialised tools may include a forensic accounting tool to research companies and a banking sector tool, or a tool for refiners to improve due diligence on IFFs when sourcing from ASGM provenance.

- Improved guidance on reporting on IFFs as part of Step 5 of the OECD Due Diligence: For example, a guide for upstream suppliers on how to report on due diligence efforts on IFFs.

- ASM formalisation initiatives tool. Improve stakeholder capacity to reduce scale and impact of IFFs on formalisation efforts. This includes how to assess if/how vested interests in IFFs might undermine attempts to legitimise/formalise an ASGM sector. For example, if a development intervention is going to set up in a formalisation initiative, how do they assess the ways in which IFFs in the existing political economy could impede or enable their project? How do they then mitigate this in project design and evaluation?

- Support whistleblowing investigative journalism. For example, by supporting the Afrileaks project.

- Financial sector assessment: how the level of development of the financial sector in ASM producer nations can create an enabling environment for IFFs.

Key discussion findings

IFFs Impede Formalisation

Formalisation does not happen in a vacuum. An informal economy does not mean unstructured or empty space. On the contrary, at any mining site, community, or province, there are structured systems in place. These are functional; the status quo is benefiting someone.

Miners are not necessarily free to formalise. This can mean bonded labour, but it can also mean social or power relationships, not all of which are nefarious. Traders, financiers, and buyers, often play a key role in the social fabric, safety nets, and survival of miners and their communities.

Gold is a financial instrument. Gold is anonymous, easily transportable, and has high value in low quantities making it uniquely suited as capital for IFFs. We need to consider the political economy and vested interests that might be disturbed by seeking to formalise the sector. We also need to develop commercial logic to make formalisation desirable and feasible for miners, traders, and financial actors.

Nuance is Essential

To adopt narrow definitions or attempt to squeeze activity and financial flows into firm categories (legal v. illegal; licit v. illicit) is counterproductive and fails to appreciate the complexity of the sector and actors involved. It also risks demonising and marginalising further the ordinary miners who are simply trying to make a living.

Informality is a widespread phenomenon and is not synonymous with criminality. Workers participating in the informal economy may utilise IFFs for complex and highly legitimate reasons.

The reality for many ASGM contexts is that legal frameworks and enforcement mechanisms are often extremely weak or regulations are impossible for ASGM miners to comply with, for example exorbitant licensing fees. While mechanisms and frameworks are being strengthened, it is useful to consider incentives and motivations behind informality.

Some actors would never wish to join the formal economy, but many of them do or would. If we consider miners and traders as business people, we can consider ways in which formality can be a subjectively better business offer than informality. A prime example is the use of gold to avoid having to use the formal banking system.

Practical Actions

An enabling environment is critical to formalisation, and understanding the role of IFFs (often an invisible hand) is important to creating such an environment. A comprehensive approach to IFFs will look at enforcement and enabling/incentive frameworks:

- Effective commercial banking sectors. Offer affordable, accessible, reliable and appropriate financial services. Improve services like in-country transfers, international import financing, reasonable service fees, ensuring cash is available, use of mobile banking.

- Enabling regulatory frameworks. Broken formal systems incentives use of informal systems. But small adjustments informed by miners, traders, creditors, and ASGM sector service providers can do as much as large legislative reviews.

- Regional harmonisation of royalty rates. Smuggling is often driven by incentives to avoid paying an origin country’s royalty rate in favour of a neighbouring country’s lower rate. By harmonising regional royalty rates, we may reduce the incentive to smuggle gold within regions.

Criminal actors are profit driven. The high profit and low risk nature of artisanal mining makes it appealing to criminal groups and actors. The sector’s informality makes mine workers particularly vulnerable to exploitation by criminals. The silver lining is that criminal actors can be displaced from a sector – whether it is narcotics or ASGM – if it becomes sufficiently unprofitable for them.

Meanwhile, criminals are exploiting some of society’s most vulnerable people – artisanal miners. It is important to recognise that the miners are often the victims, and at the same time they are sometimes complicit in complex systems of victim and victimiser.

Improve Data Collection and Analysis

Consistent, comprehensive, and comprehensible data is desperately needed to better understand and address IFFs. Not all of this need be done from scratch.

Collating Data. There is data already out there (for example, work by the UN Group of Experts, research institutes, academics, governments). The challenge is accessing this sometimes sensitive and confidential data, bringing that knowledge together, making it accessible, and making it readable in a fashion that encourages people to engage with it. If this isn’t taken in mind, there is a risk of duplication.

Validating Data. While collating existent data, it should not be taken at face value. It is not always reliable. In particular, consider ‘footnotes to nowhere’ which feature recycled statistics, sources, and data from circuitous pathways.

Gathering Data. IFFs are long, complex and span the globe. As such, data collection requires various techniques and partners. Upstream, to address knowledge gaps requires developing local expertise, research, communications, and reporting. Toolkits and models should equip local expertise to do the research and apply findings to their immediate circumstances.

Reporting Data. Data need not be academically sourced. The private and financial sectors have the potential to play an important role. Companies under Step 5 of the OECD framework could contribute to data sets by providing detail, standardised information, or clearer communication.

Securing Data. Research on IFFs is extremely sensitive and may be risky to collect, hold, or publish.

Engage a Wider Range of Key Stakeholder Groups

Efforts to address IFFs will fail without consideration of a broad swath of stakeholder groups, including some not always associated with ASGM work: financial institutions, law enforcement, and downstream industry. Those currently active in formalisation efforts, such as development organisations and governments, may need to recalibrate their approach.

Local Institutions and Upstream Actors

Local institutions and upstream actors (such as diggers, miners, traders, creditors, landowners) must be included in efforts to understand and respond to IFFs, and to report to their customers on their actions. Often these actors are not included in conversations on IFFs linked to ASGM, with development actors talking about them rather than with them. As emphasised by representatives of local organisations at the dialogue, local groups and those directly engaged in ASGM often possess a wealth of information and are best positioned to gather additional data and intelligence.

Financial Institutions

Under-development of financial sectors is a key impediment and barrier to formalisation and exacerbates incentives to utilise IFFs. Ways to better engage this sector include:

- Local dialogues. We need to better understand how finance works at the local level, the risks

they face, and how they compete, enable, or work in parallel with IFFs and the ASGM sector. We

need to understand how financial underdevelopment makes the ASGM sector vulnerable to the

generation and cleansing of IFFs, and what the different stakeholders can do to tackle this risk. - Support financial banking institutions to conduct robust due diligence. Financial institutions

may have mechanisms and processes to conduct due diligence but overlook issues of ASGM. - Finance ASM. Financial engagement with ASGM need not be exclusively risk-mitigation. There

are opportunities for commercial establishments to finance or invest in ASGM.

Development Orgs & Governments

Policy frameworks and donor approaches are often designed for industrial mining, and not for ASM. ASGM formalisation is a very difficult issue, but it is something where we know the problems very well, but not the solutions. There is a tendency to jump at things that sound easy but are actually complicated, such as developing cooperatives, as the magical basis for facilitating formalisation.

Downstream

Responsible refiners sourcing from artisanal miners prioritise those already formalised and legitimised, such as enterprises certified by the Fairtrade and Fairmined standards. Through those certifications, risks are managed. So far, the supply chain due diligence process has often made it less desirable for the market to source from artisanal miners outside of these ‘gold standard’ certifications. An opportunity exists to plug that gap with the ARM and Resolve Market Entry Standards presently at concept phase.

Sourcing bans – formal or de facto – on ASGM is problematic from a development point of view, a sustainability point of view, and because it marginalises people further who are already marginalised in the sector. The premise of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance is to enable engagement in mineral sectors in fragile areas.

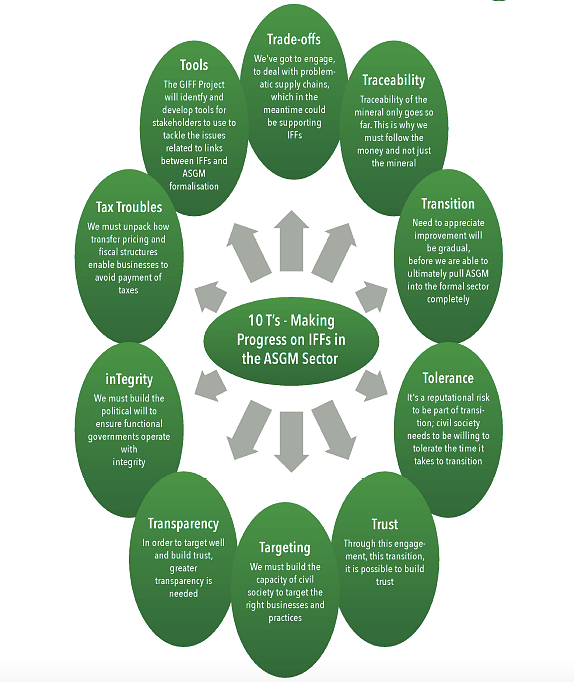

Ten ‘Ts’ for Making Progress on IFFs in the ASGM Sector

Building from the concept of the ‘3Ts’ in conflict minerals, the event concluded with the GIFF Project Director – with input from participants – sharing ‘7T’s’ derived from the dialogue, that can help stakeholders drive impact in reducing the influence IFFs have over ASGM formalisation. As we have reflected on the transcript of the event, these have evolved into the ‘10Ts’ for making progress on IFFs in the ASGM Sector.

Trade-offs

The fact the ASGM sector has a relationship to IFFs could be off-putting, incentivising responsible or brand-exposed businesses to avoid engagement with the sector altogether. A refiner or jeweller might say, ‘no thank you, this is too hard, too risky.’ But ASGM sustains rural economies in developing countries and is a critical livelihood and lifeline for millions of people around the world. So we’ve got to engage, to deal with problematic supply chains, which in the meantime could be supporting IFFs. The OECD DDG gives us mandate and a framework for doing this.

Traceability

Traceability of the mineral goes only so far. You can have an entity that is legally registered, with appropriate documentation, but illicit financial flows could well be flowing through those entities because there are ways of fiddling the books. It’s hard to spot these things with ordinary due diligence practices. Governments and businesses must follow the money, not just the mineral.

Transition

Transforming a sector from criminality or informality to legitimacy may require temporary complicity. Businesses may need to engage with imperfect or problematic partners in order to build their capacity and will to do business responsibly gradually, and ultimately either pull them into the formal sector more completely or abandon the relationship in time.

Trust

Through this engagement, this partnership in transition, it is possible to build trust. This is especially important between creditors and miners, between buyers and miners, between importers and exporters, and also between civil society and business.

Tolerance

It’s a reputational risk to be part of the transition, and businesses taking this risk need to be given a chance. If civil society seeks perfection too quickly, and aren’t willing to tolerate the time it takes to transition, then brand-exposed businesses will be less inclined to bring to bear their weight, influence, and ability to leverage change in the informal sector. Sectoral transformation towards formality may then take longer to happen.

Targeting Well

We must build the capacity of civil society to do their role as whistle-blowers and investigators well and target the right businesses whose practices are not constructive. We must build the capacity of business to judge which problematic business opportunities merit the risk both commercially and sectorally for tolerating imperfection, so they invest their resources wisely.

Transparency

In order to help stakeholders target well and build trust, civil society calls on governments, companies, and initiatives like the GIFF Project to put information built on reliable data into the public domain and explain it. There remains the need for strategies to manage sensitive data whose release could create security issues for the people or institutions involved. There remain issues around laws that enforce secrecy and prevent disclosure, which act as a barrier to transparency but enable business to be done more freely.

inTegrity

We must seek to uncover and report the truth, and make decisions based on integrity. We must support political will where it exists and build political will where it does not to ensure governments in ASGM producer, trading and consumer states operate with integrity, in the interests of the nation and in accordance with international commitments to transparency, human rights, and responsible business.

Tax Troubles

We must unpack how transfer pricing and fiscal structures enable businesses to avoid payment of taxes so denying governments of producer nations the revenues they sorely need to build functional states.

Tools

The GIFF Project will identify or develop tools for stakeholders to use to tackle the issues related to links between IFFs and ASGM formalisation.

Context

The GIFF Project has illuminated a broad consensus that illicit financial flows (IFFs) pose a significant obstacle to development goals in the artisanal mining sector and their potential solutions are poorly understood.

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is often informal and unregulated. Its participants include the most vulnerable of society, often lacking basic human right and social protections. Gold’s special properties – including its utility as a financial instrument and high value in extremely small qualities – set it apart from other artisanal and small-scale mining sectors. In particular, the sector is vulnerable to criminal exploitation and IFFs, which may enable criminal activity, inhibit formalisation efforts, and facilitate mercury distribution. Specifically, gold produced by ASGM has been linked to IFFs in Africa’s Great Lakes Region, West Africa (Hunter, M., “Case study: The artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector,” (Paris: OECD, 2016)), and Latin America (FATF and APG, Money laundering and terrorist financing risks and vulnerabilities associated with gold (Paris: FATF; Sydney: APG; 2015, pp. 12-13, 16, 17).

Initial assessments of gold IFFs reveal a complex web of financial flows, materialising before gold even leaves the ground. IFFs can be cyclical in nature, with illicit profits reinvested into gold operations, further perpetuating IFFs. Consequently, “following the money” is crucial to identifying actors profiting from IFFs, as well as understanding the enablers driving the flows (informal systems, porous borders, weak oversight, lax oversight in transit and destination countries, etc.) and generating effective responses.

The GIFF Project

The Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime and Estelle Levin Ltd. have undertaken the GIFF Project to:

- Increase understanding of to what extent and in what ways IFFs are an impediment to the

formalisation of ASM supply chains; - Better understand the vulnerability of the international gold sector to criminal infiltration;

and - Strengthen local and international responses to IFFs.

Throughout 2016, the GIFF Project will develop a toolkit to arm stakeholders with knowledge and tools to better identify and combat IFFs in the gold supply chain that impede formalisation of the sector. It will assess the various forms and functions of IFFs in ASGM, analyse existing legal frameworks related to these flows, and prescribe ways to address and prevent illegal activity in gold supply chains.

Fieldwork is currently being shaped to use local ASGM experience, perspectives, advice and needs to inform the development of the toolkit.

In 2017 the GIFF Project anticipates extending its work on gold to include field investigations, and local and regional dialogues as the basis for driving solutions on the ground. The GIFF Project is also engaging with stakeholders keen to unpack the relationships between IFFs in artisanal diamond and coloured gem sectors. If you are interested in supporting or participating with us on a concrete project to help us drive impact in this arena, we would love to hear from you.