Posted on 17 Oct 2018

Originally published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in October 2018.

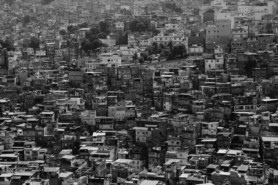

Life in Maré, a Brazilian slum controlled by criminal groups, reveals the urban security challenges faced by cities around the world.

As soon as our car entered the Maré favela complex, a sprawl of run-down buildings in northern Rio de Janeiro, the driver opened all the windows and placed on his dashboard a sign bearing the name of a local NGO. I had come to Maré to carry out research into Rio’s criminal groups, and their control of the neighbourhood was the reason for the driver’s behaviour.

His actions are standard practice for outsiders entering gang and militia-controlled territories in Rio. Lowered windows tell undercover scouts that the car is not carrying police officers or armed rivals, while the sign connects the visitor to a trusted local presence.

But I found other sights on the long drive through through Maré much more surprising. We travelled down a thriving, if chaotic, commercial road that serves the 130,000 residents of one of Rio’s largest slums. The street was lined with clothing and electronics shops, fruit sellers and mid-sized supermarkets. I had been researching the territorial presence of Rio’s gangs and militias for some time, and this road got me thinking about the informal negotiations needed to get daily supplies of fresh produce and cargo into an area where an armed group holds territorial control.

My destination in Maré was a couple of NGOs – including the one named on the driver’s sign – that offer public services, a resource much rarer than the products found on the area’s main street. My first meeting was at Redes da Maré (Networks of Maré), which serves as a public ombudsman of sorts, where locals report abuses by the different armed groups, including the police.

It also runs courses that teach locals skills they would otherwise have to commute for hours to learn. During my visit, a workshop for small business owners (probably from the shops I had just seen) was so packed that those taking part had to borrow chairs from the NGO’s small library.

Guns on the streets

‘The number of armed civilians has increased tremendously in the past four years’, said Patrícia Vianna, a coordinator for public security at Redes. ‘At each step you take, you meet a group of armed people’. I had seen one group for myself – a cluster of young men, seemingly teenagers, holding rifles and chatting on a street corner. They looked calm, almost bored.

In that four-year period, public security across Rio has deteriorated, as economic and political crises have contributed to the demise of a public policy that had previously made strides in fighting organised crime in some favelas (although not so much in Maré). Areas targeted in the ‘pacification’ strategy saw initial armed interventions by military police followed by the permanent presence of a special pacifying police unit. Then came other public services and institutions – many of which had never reached these neighbourhoods before.

Between 2008 and 2012, the strategy worked sufficiently well to be hailed as international best practice by the World Bank and others. My visit to Maré was part of a study into the strategy’s decline, and an attempt to discover why, in February 2018, the federal government stepped in and gave temporary control of all Rio’s security institutions to the armed forces.

A few years ago, Maré itself served effectively as a laboratory for military intervention in a densely inhabited (and deeply impoverished) urban area. Between April 2014 and June 2015, 2,500 soldiers patrolled the slum with the help of armoured vehicles. For a time, homicide rates fell drastically (from 21 to 5 per 100,000 inhabitants according to the Ministry of Defence).

However, as Patrícia told me, the gains were short-lived. Local authorities said that a contingent of pacifying police officers was being trained for the huge task of policing Maré. But this last and crucial leg of the project never took place. ‘What happened was a huge expenditure, running into millions of reals, for nothing more than armed clashes.’

Official numbers also suggest a failure to sustain the gains of the military occupation: the total number of intentional homicides (including deaths related to police intervention) in and around Maré rose by 312% from 2015 to 2017 (reaching 132 killings last year). Three years after the withdrawal of military forces, Maré is firmly back in the grasp of criminal factions.

Different factions control different chunks of the territory – there there is an invisible borderline between territory I visited, controlled by the Red Command (Comando Vermelho) gang, and that of their rivals the Third Pure Command. Militias operating extortion rackets control a smaller area of the slum.

During my visit I spoke with Luke Dowdney from Fight for Peace, which offers young people in Maré a safe space to practice boxing and study. The boys and girls he works with have witnessed some of the common punishments meted out by gangs, such as murders and beatings, as well as frequent gunfights for territorial control. Many have trouble sleeping and suffer psychological problems as a result.

Disputed territories – a global security risk

The trauma inflicted by criminal groups on local people is just one of their negative effects. Disputed urban territories offer safe haven to illicit economies and are characterised by high-intensity armed activity in which governance challenges and the activities of non-state armed groups converge, affecting the rest of the urban system through extortion rackets, robberies, cargo theft and unsafe public transportation. Maré, for instance, is located next to two critical routes connecting Rio to other cities, one of which is also the main artery from the international airport.

The security problems faced by the people of Maré have global relevance. Such disputed territories are not yet widely recognised as a threat to national security and development. But this is very likely to change as cities grow and policymakers realise, as Rio’s leaders have, that failure to address weak links in large cities paves the way for recurring instability. As urban populations rise across the developing world, especially in Africa and Asia, many countries face similar dilemmas of negotiating with – or confronting – territory-holding armed groups.

Luke told me: ‘Some things that happen here do not take place in cities in peace.’ He was referring to an operation in June, when a police helicopter flying over Maré fired at suspected criminals. During the operation, which also included four armoured vehicles, seven people were shot dead, including a 14-year-old boy on his way to school. Luke continued: ‘This is not a war, but certainly not peace either.’

–

The author would like to thank the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GITOC) for its support to this research. In January the IISS and GITOC will publish a full report on the use of the armed forces and other public policies to counter territorial presence of criminal groups in Rio.