Posted on 26 Feb 2024

1 February 2024 marked the third anniversary of the coup in Myanmar. Although there is much geopolitical tension and conflict at the moment occupying people’s minds, with developments in the Middle East and Ukraine particularly dominating the news, the situation in Myanmar been delicately avoided by donors and international partners for some time.

However, as the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index shows, organized crime in Myanmar has significantly worsened, to the point that the country currently has the highest levels of organized criminality in the world.

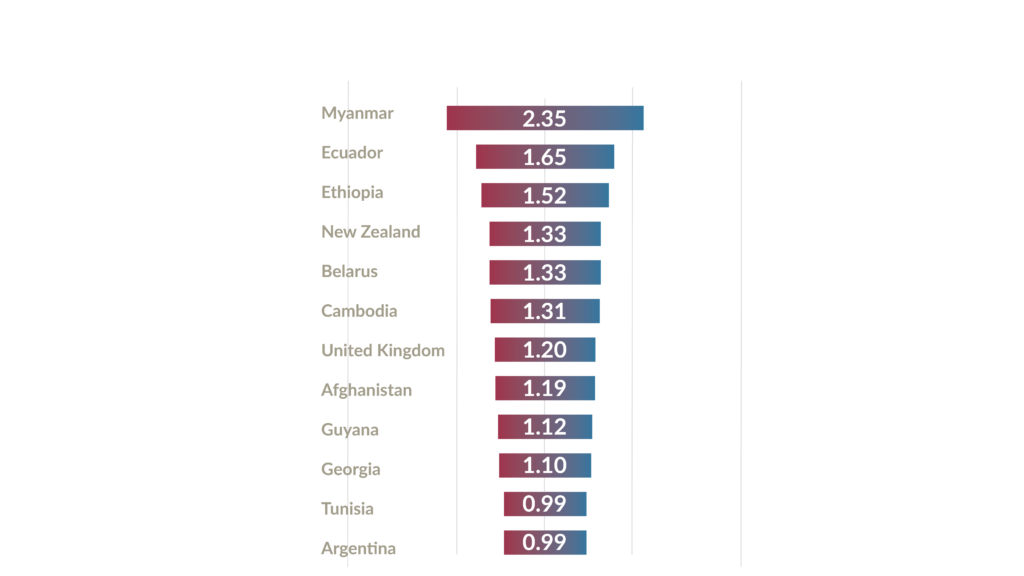

Furthermore, Myanmar’s resilience to organized crime has weakened significantly since its low ranking in 2021. The gap between its criminality and resilience scores is so large that it has no meaningful global comparator. This calls for urgent intervention in Myanmar and could be a cautionary tale for countries such as Ecuador and Haiti, whose emerging crime–resilience gap scores may not be at this critical juncture yet but are steadily approaching Myanmar’s dire, unenviable situation.

In 2021, Myanmar’s criminality score of 7.59 (out of 10, where 10 is the worst ranking), placed it third among all countries in the world. By 2023, a score of 8.15 propelled Myanmar to the top of the global ranking, i.e. it has the highest levels of criminality globally. The most significant increases in its criminal market scores (one component of the criminality ranking) were in non-renewable resource crimes (following a surge in illegal rare earth mining after the 2021 coup) and human trafficking, where cases of forced labour and of trafficking for forced criminality and marriage, as well as the plight of the Rohingya people, were exacerbated by the conflict and subsequent sanctions imposed by the international community.

Myanmar’s score for criminal actors (the other component of the criminality ranking) also jumped between 2021 and 2023 – with a particular upward trend for foreign (namely Chinese) actors operating in the country – to a record 9 out of 10. This now matches the score also reached by state-embedded actors, who are active in most, if not all, criminal markets. In particular, state-embedded actors are facilitators in Myanmar’s drug markets (where the country scores 10 for synthetic drugs). Overall, Myanmar has the highest combined score for criminal actors in the world.

But the biggest shifts are seen in Myanmar’s ability to resist and withstand organized crime. The Index shows that the more a country is affected by conflict or instability, the more likely it is to have reduced resilience to organized crime. Myanmar is no exception. The country’s resilience score, already low at 3.42 (out of 10) in the 2021 edition of the Index, slid to a paltry 1.63 in 2023. This is not the lowest score in the world – Libya and Afghanistan rank lower – but two key findings are nonetheless striking. First, the country has seen a drop of between 1 and 3 points in every single resilience indicator. Second, and perhaps most importantly, the gap between criminality and resilience is so large that it puts Myanmar eons away from any other country. In 2021, the gap between criminality and resilience was 4.17 points, but by 2023 it had widened to an alarming 6.52 points (the gap ‘growth’ between 2021 and 2023 is shown in the figure below, alongside other countries that also experienced growth gaps).

The biggest resilience score drop was seen in the international cooperation indicator, which fell from 5.0 to 2.0. Much of this can be explained by the decisions of many international partners not to engage directly with the military government, and Myanmar’s exclusion from international forums, and information and exchange mechanisms until the coup is resolved. Donors suspended their government-to-government aid agreements, partnerships and projects after the coup, and promised to support more civil society and humanitarian projects. However, these promises may not have been realized.

Aid delivery and programming in Myanmar is challenging. Civil society and communities are literally under fire; there are difficulties in getting funding into Myanmar (possibly complicated by the unintended consequences of the Financial Action Task Force blacklisting); and there are concerns about the safety of project staff. Data from the OECD shows a considerable 85% drop in overall aid contributions since 2021 – arguably at a time when intervention and support are most urgently and desperately needed. There were other demands on donors during this period, such as Ukraine, which saw a surge in aid in 2022. However, in December 2023, the UN reported ‘gross underfunding’ for the estimated 1.9 million people who had been prioritized for aid.

The drop in donor activity and aid, and the knock-on effect of limited programming and interventions, has also affected the ability to monitor the situation in Myanmar. This has been exacerbated by a significant decline in the resilience capacity of non-state actors. This is not surprising, given the well-documented targeting of civilians and the repressive tactics of the military government.

The conflict in Myanmar has not only increased vulnerability, but the resulting lawlessness has fuelled crime and enabled new illicit markets to consolidate. Myanmar scores 7.5 for the cyber-dependent crimes market. Cyberscam centres have sprung up across the country, particularly in border towns and special economic zones, facilitated by state-embedded and Chinese actors.

The cyberscam phenomenon is also an example of how domestic criminality, if left unchecked and unregulated, can affect the stability and security of neighbouring countries – such as Thailand –, the wider region and the world. The scale of cyberscam activity has become so significant that it appears to have even affected China’s delicate geopolitical balance in the region, eventually forcing Beijing to issue arrest warrants for key figures linked to cyber fraud in Myanmar’s Shan State. The absence of scrutiny in Myanmar has therefore not only contributed to the widening and deepening of the country’s crime–resilience gap, but has also been instrumental in allowing rising criminality to have reach and impact far beyond its borders.

While cyber fraud in Myanmar has attracted much international scrutiny and attention, it is primarily a manifestation of an internal, complex picture of intertwined criminality, vulnerability and risk. The ‘gap’ that exists for Myanmar is a canary in the coal mine for us all – it needs to be top of the agenda in 2024 for governments and civil society practitioners alike. Prescribing a tonic of acute diplomatic attention, rapid redirection of aid and programming efforts that navigate complexity to create innovative solutions to address state-embedded criminality while supporting and building community resilience is an urgent imperative for the country.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.