Posted on 11 May 2021

On 2 March 2021, Niger police seized 17 metric tonnes of cannabis resin, the country’s largest recorded shipment of hashish. The seizure happened in a warehouse in the capital, Niamey.

Large drug seizures are not uncommon in Niger, which has long been a major transit hub for cannabis resin originating in Morocco and cocaine trafficked from West Africa destined for Libya (and eventually Europe) or the Gulf. However, the hashish – stamped with markers such as ‘the face of happiness’ ( وجه السعد ) and ‘the fingerprint’ ( البصمة ) – had not arrived from Morocco. Rather, it had come from Lebanon, along a circuitous route through the Gulf of Guinea. The origin of the shipment underscores the diversification and dynamism of hashish trafficking routes between the Middle East and North Africa, with Niger playing a role as a key entrepot of the Sahel.

Old drugs, new routes

The seized hashish was worth an estimated CFA20 billion (US$37 million). The operation was the result of a four-month investigation and led to the arrest of 13 people, including 11 Nigeriens and two Algerians. Contacts indicate that at least three distinct networks collaborated on the shipment, with the markers on the drugs denoting what belonged to which network. In addition to Nigeriens and Algerians, members of the networks hailed from Mali and Libya.

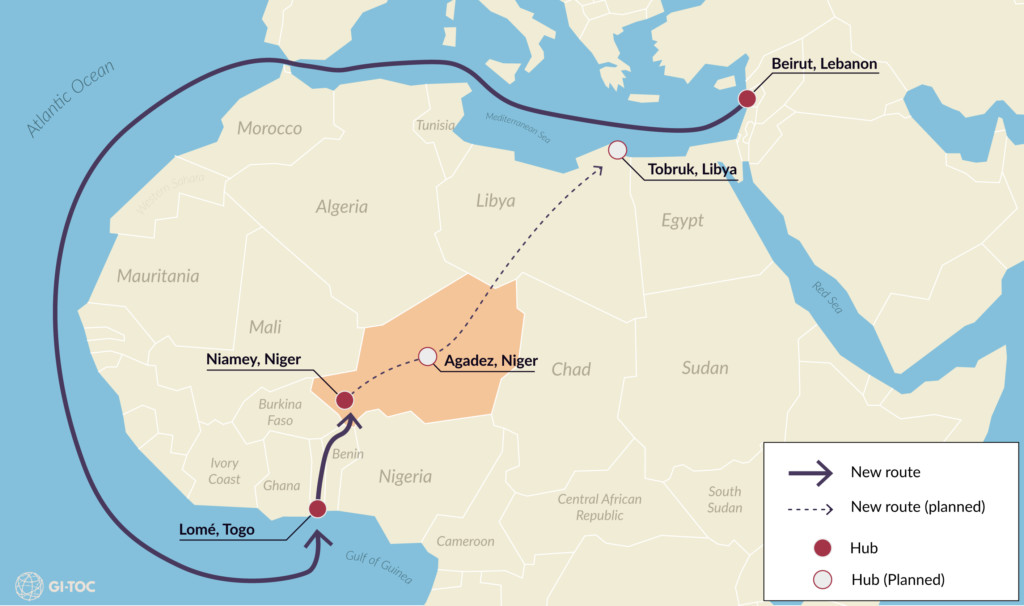

Niger routinely seizes drug shipments, mainly hashish, but also cocaine and psychotropic pills (such as Tramadol). However, none have been as large or as valuable as this. But this seizure also stood out for the provenance of the drugs. Normally, hashish seized in Niger comes from Morocco’s northern Rif region. Shipments destined for Libya are moved south and east through Western Sahara, Mauritania and northern Mali, where state control is more limited than in Algeria (though Algeria, too, has seen rising shipments in recent years). From Niger, hashish routes stretch north, to Libya, or east, to Chad and Sudan. However, the hashish found in the Niamey warehouse originated in the Middle East, having been shipped out of Beirut, Lebanon – the first time drugs of this provenance have been seized in Niger.

According to Niger’s Central Office for the Suppression of Illegal Traffic in Narcotics, the drugs were transported by commercial shipping to the port of Lomé, Togo, where they were loaded onto a Benin-registered truck, hidden in packages labelled as fruit and then driven north, across the border, into Niger. When seized, the shipment was being prepared for onward transport to the northern city of Agadez, and from there to the coastal city of Tobruk, in eastern Libya.

The shipment’s route is surprising, given that substantial volumes of hashish from the Middle East, primarily grown in Lebanon and Syria, are regularly shipped directly to northern Libyan ports, such as Tobruk, as well as al-Khoms and Misrata, before being distributed locally, or reshipped to Europe or smuggled into Egypt. Had it not been seized, this consignment would have ended up in the same markets – likely in large part destined for Egypt via Tobruk, which makes the use of a much longer and complex route involving maritime and land transport through four countries seem surprising.

Nonetheless, according to one source, the Lebanon–Togo–Niger route is not new, having emerged around 2018. To date, though, it has been rarely used. However, as the seizure on 2 March shows, this may be changing.

There are several possible explanations why traffickers use this route. First, there is reportedly saturation at the Libyan ports, as routes from the Mediterranean to Libya are believed to be operating at full capacity. Traffickers without contacts at the country’s ports face challenges in accessing the ports, leading some to seek the alternative, but roundabout, Niger route.

Secondly, changes in the security situation in the central Sahara have had the effect of thwarting smuggling routes in the region. Primarily, this has involved heightened surveillance and interdiction by foreign militaries – mainly France and the US – as well as rising levels of regional violence and banditry. This has led to a substantial rise in transport costs since around 2013. According to a contact in southern Libya, the disruptions have become more acute recently, and may have led to a drop in the volume of hashish moving through the area.

The difficulties encountered by Moroccan traffickers on central Sahara routes transiting northern Mali may therefore have provided an opening for Levantine traffickers to edge in on the market using routes from the Gulf of Guinea to Libya via Niger, which limit exposure to much of the said challenges.

If the use of this maritime route to move drugs from Lebanon to Libya via Niger were to grow, it could spell a significant shift in Sahel trafficking patterns, and suggests that, despite the longer distances and extra border crossings, the Niger route could prove a cost-effective alternative to more direct maritime routes for traffickers.

When drug busts are seen as political

The seizure is also important not just for where it happened, but for what happened to the drugs and who was involved. Despite claims that the seized cannabis was incinerated, our contacts indicate that part of the shipment was reacquired by the trafficking networks involved. As of early May, at least four tonnes of hashish from the shipment had reportedly arrived in Tobruk, Libya.

The Nigerien anti-drugs agency (OCRTIS) categorically denied that any drugs from this seizure leaked back into the market. A spokesperson for OCRTIS, Dr Moutari Habou said that the disposal of the 17 tons of cannabis resin was made in the greatest transparency, insisting that it would have not been possible for a part of this haul to be fraudulently subtracted. (The OCRTIS statement in French can be read in full here, and the translated English version here.)

“Indeed, three special units secured the operation: from the seizure, through the guarding of the site where the drug was stored, and its transport to the incineration site: in such a way that it is impossible for such a scenario happen.”

The spokesperson underscored that the 17 tons were incinerated on 24 April 2021 in accordance with article 142 of ordinance 99-42 of 23 September 1999 relating to the fight against drugs in Niger in the presence of the interior and justice ministers, members of the National Drugs Control Commission, judicial authorities, officials of the Defense and Security Forces, technical partners, civil society and the national and international press.

Beyond the fate of this record haul, among the people arrested following the seizure were relatives of deceased Agadez businessman Cherif Ould Abidine, a well-known drug trafficker and sponsor of former president Mahamadou Issoufou’s Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS-Tarayya). This trafficking network reportedly retains some ties – facilitated in part by a shared Arab community base – with recently elected President Mohamed Bazoum (a founding member and leader of the PNDS-Tarayya).

Such connections fit patterns seen previously in Niger. Trafficking networks allegedly enjoy close ties with political elites, whose complicity, secured by significant direct and indirect financial incentives, is essential to allow the movement of large quantities of drugs across Niger. In a context of political tension, however, these connections can expose drug trafficking operations to risks of political interference.

The timing of the incident, coming soon after a contested presidential election on 21 February in which Bazoum claimed victory, has led to questions about whether political dynamics may have played a role.

There are significant underlying political tensions and competition between different factions of Niger’s political and military elite, which were heightened during the recent elections. Contacts have intimated that elements of Niger’s military elite, notably among the ethnic Djerma (or Zarma) community – who have tended to occupy high-ranking positions in the army and presidential guard – perceive Bazoum’s election as a threat, fearing they may be replaced and lose their long-standing dominance in the military. This concern, which could also be linked to an abortive coup attempt by a Nigerien air force officer on 31 March, is perceived by some in Niamey as having potentially incentivized Djerma-dominated security forces to seize the hashish shipment belonging to Arab networks linked to Bazoum.

The reacquisition of much of the hashish by the traffickers supports the claims that the seizure was mainly symbolic and political in nature, intended as a public strike at actors close to the president’s network, rather than a credible attempt to curb drug trafficking in the region.

Regardless of their veracity, rumours of political machinations linked to the hashish seizure are problematic indications of weak trust in the rule of law and the integrity of official institutions and actors in Niger when it comes to drugs. This could foreshadow new challenges for the region, as the emergent route between the Gulf of Guinea and Libya entrenches Niger as a drug trafficking nerve centre.

This new route allows traffickers to circumvent increasingly problematic areas of the Sahel, such as northern Mali, which increases the likelihood that more drugs will flow through Niger. Hence, the country might become an alternative hub for Levantine hashish trafficking.

This shift risks significantly impacting Niger’s political and security dynamics by strengthening organized crime networks, feeding into existing collusion between such networks and the Nigerien state, and further incentivising corruption of government officials and security actors. It may also encourage deployment of law enforcement for political ends. Such dynamics, if they play out this way, present a threat to the country’s already fragile political stability and weak governance system, and could heighten the risk of political violence and conflict.

This article has been updated to include a statement issued by the Nigerien anti-drugs agency (OCRTIS) on 29 May 2021.

Cover picture: Benin-Niger border crossing in Malanville (YoTuT)