The latest storm makes groundfall in Haiti

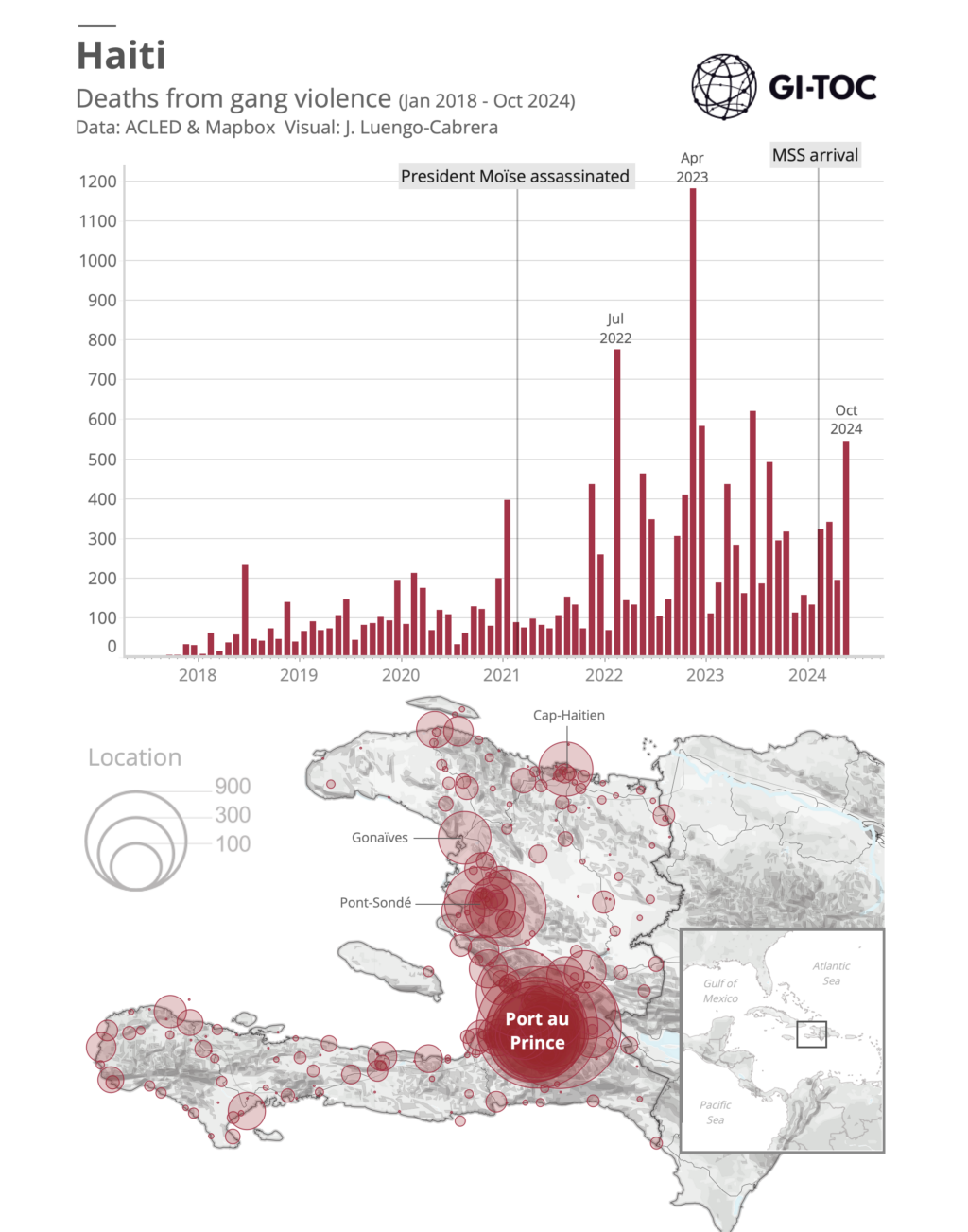

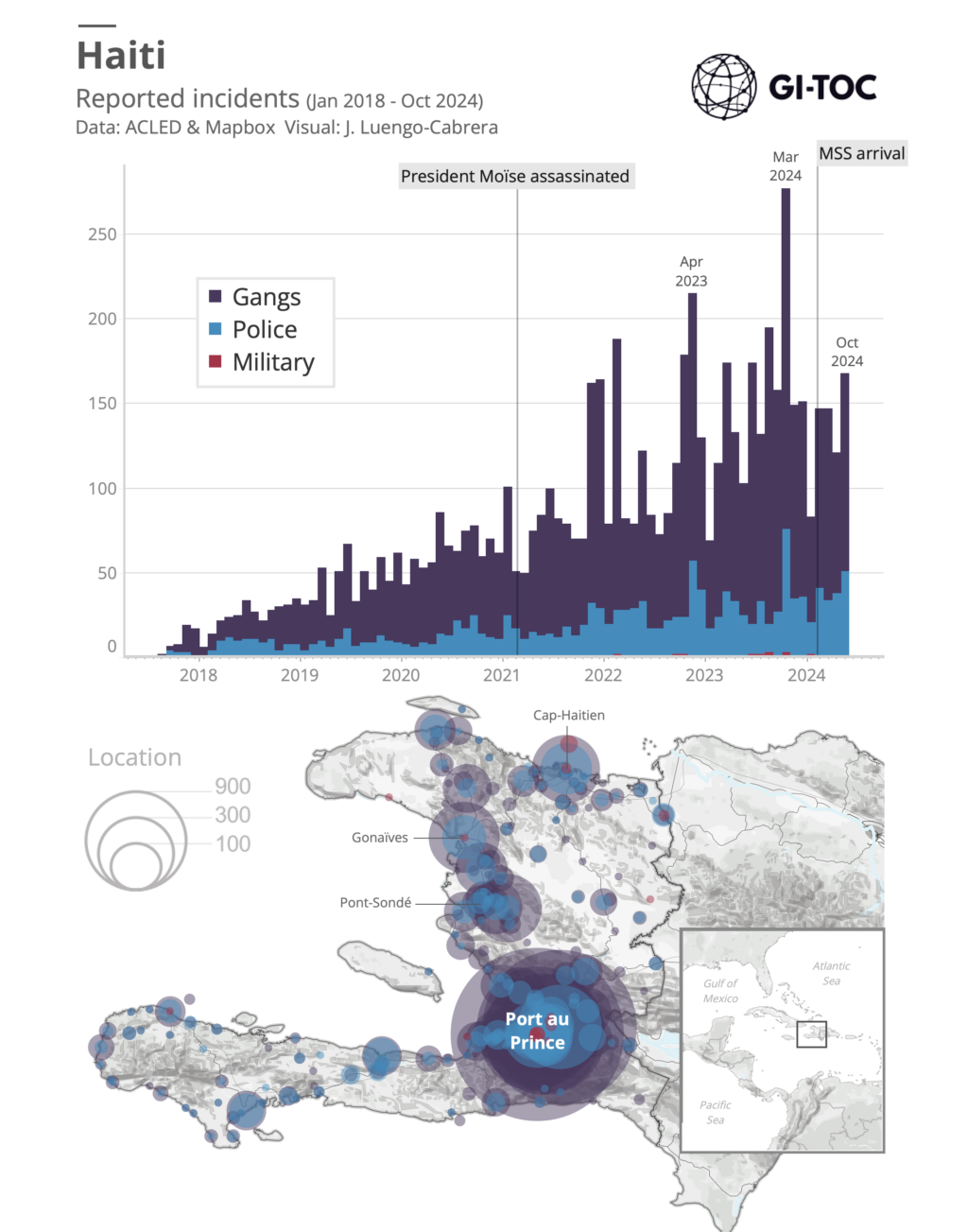

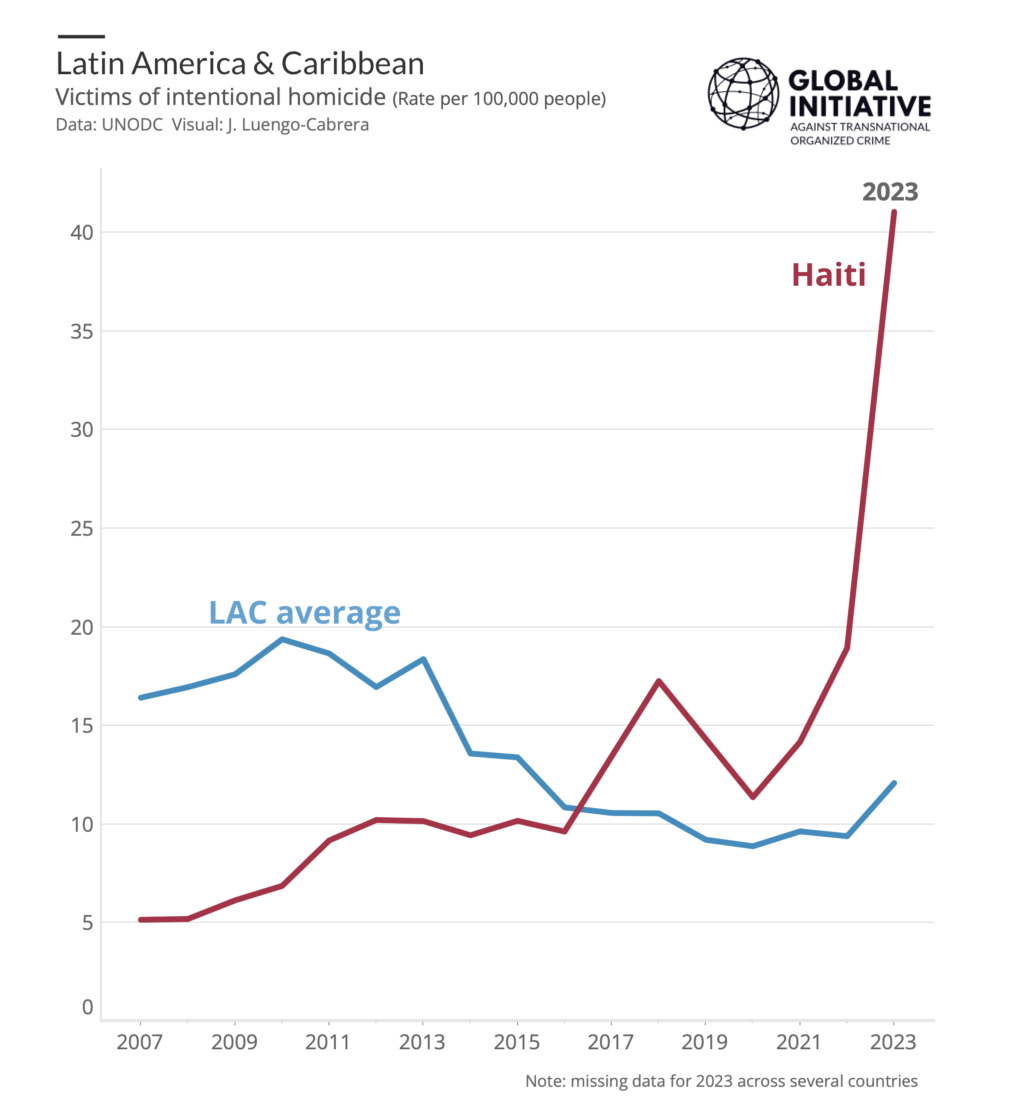

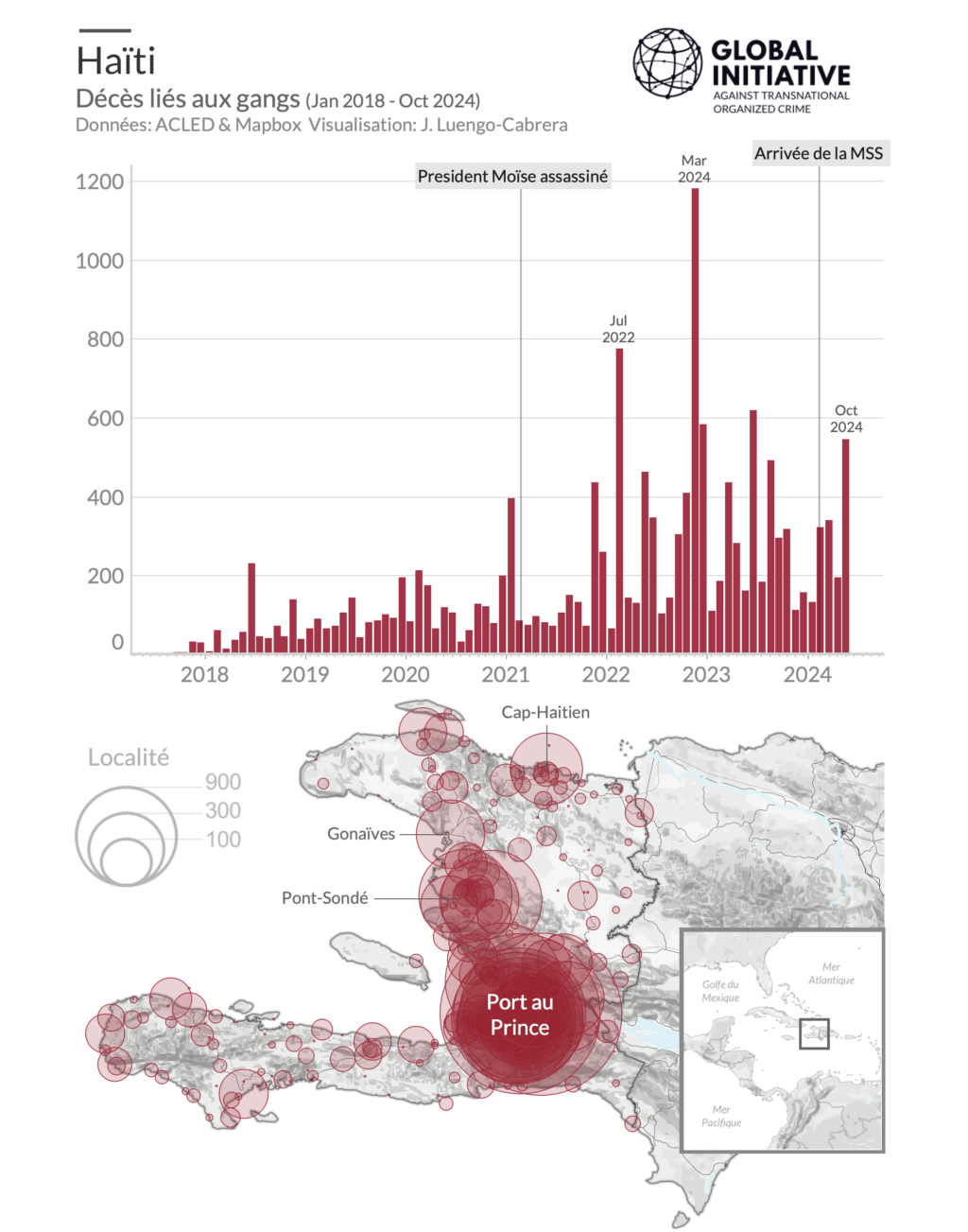

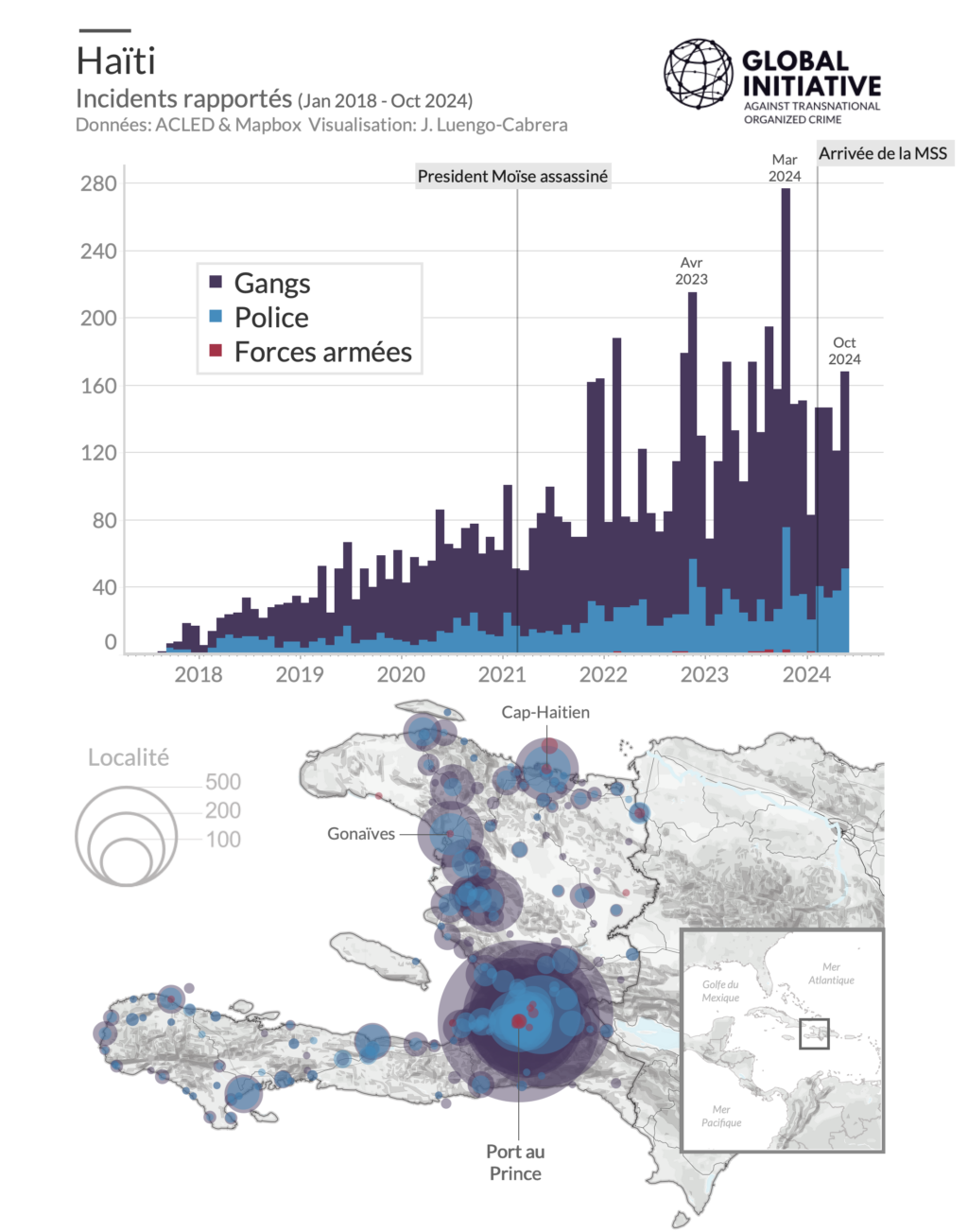

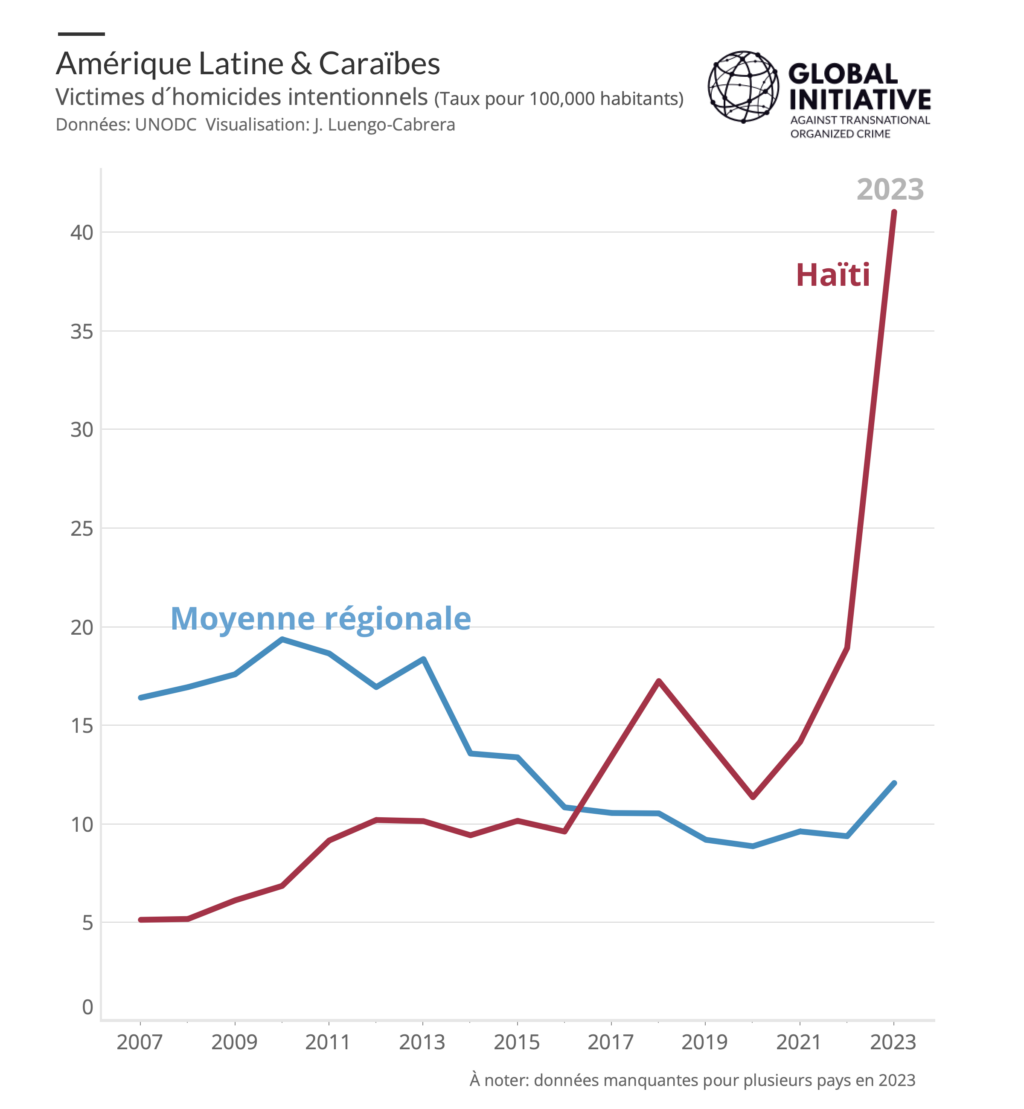

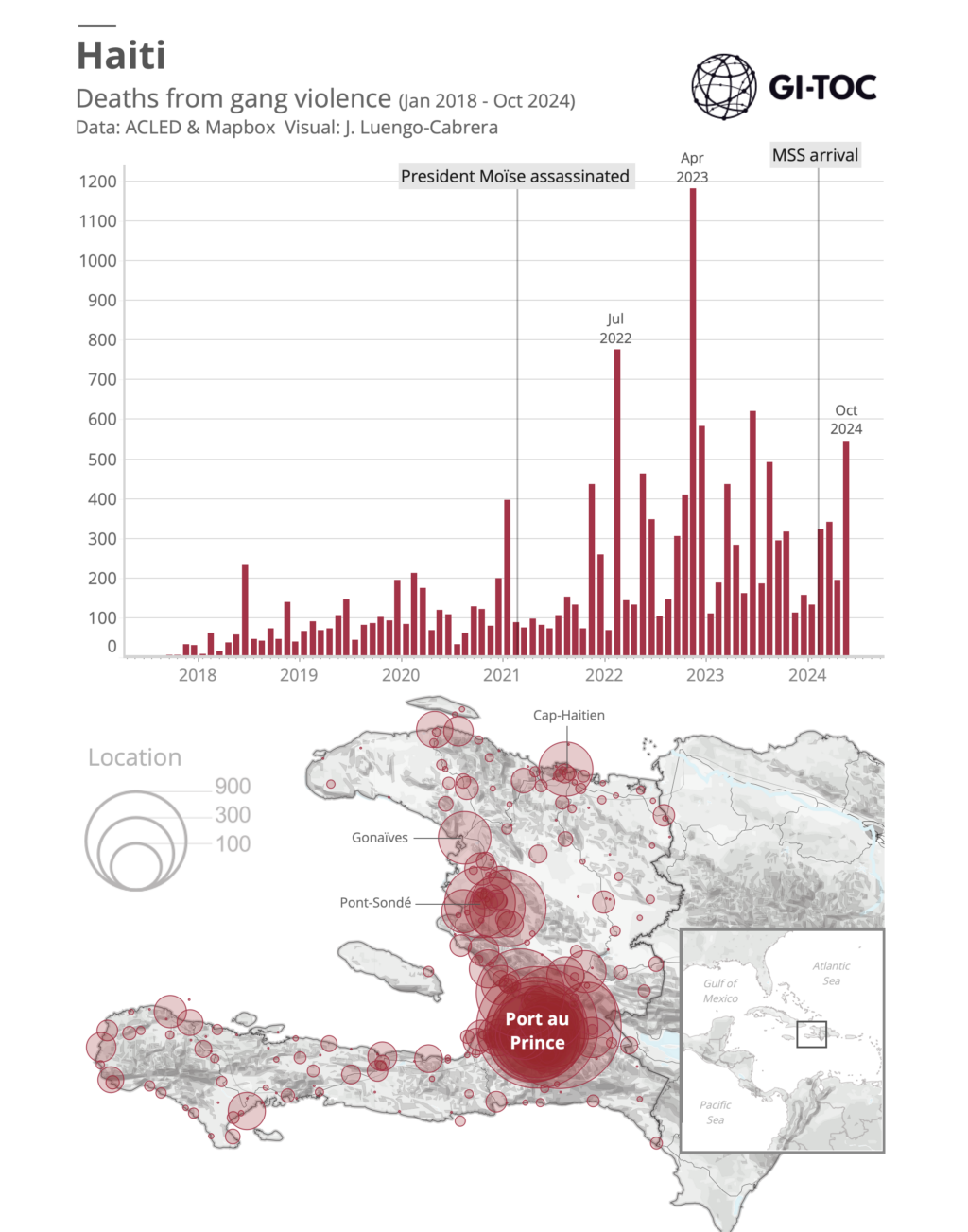

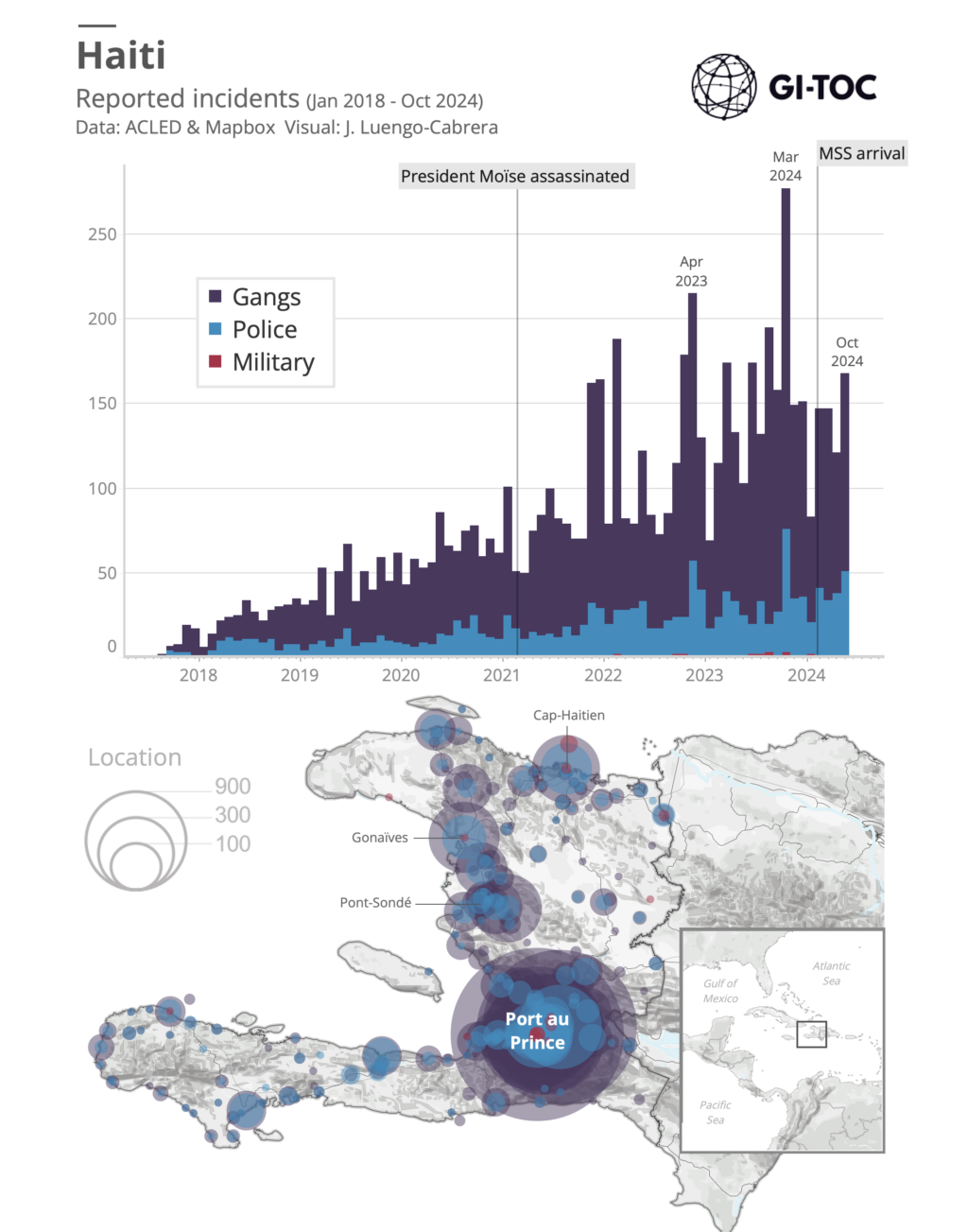

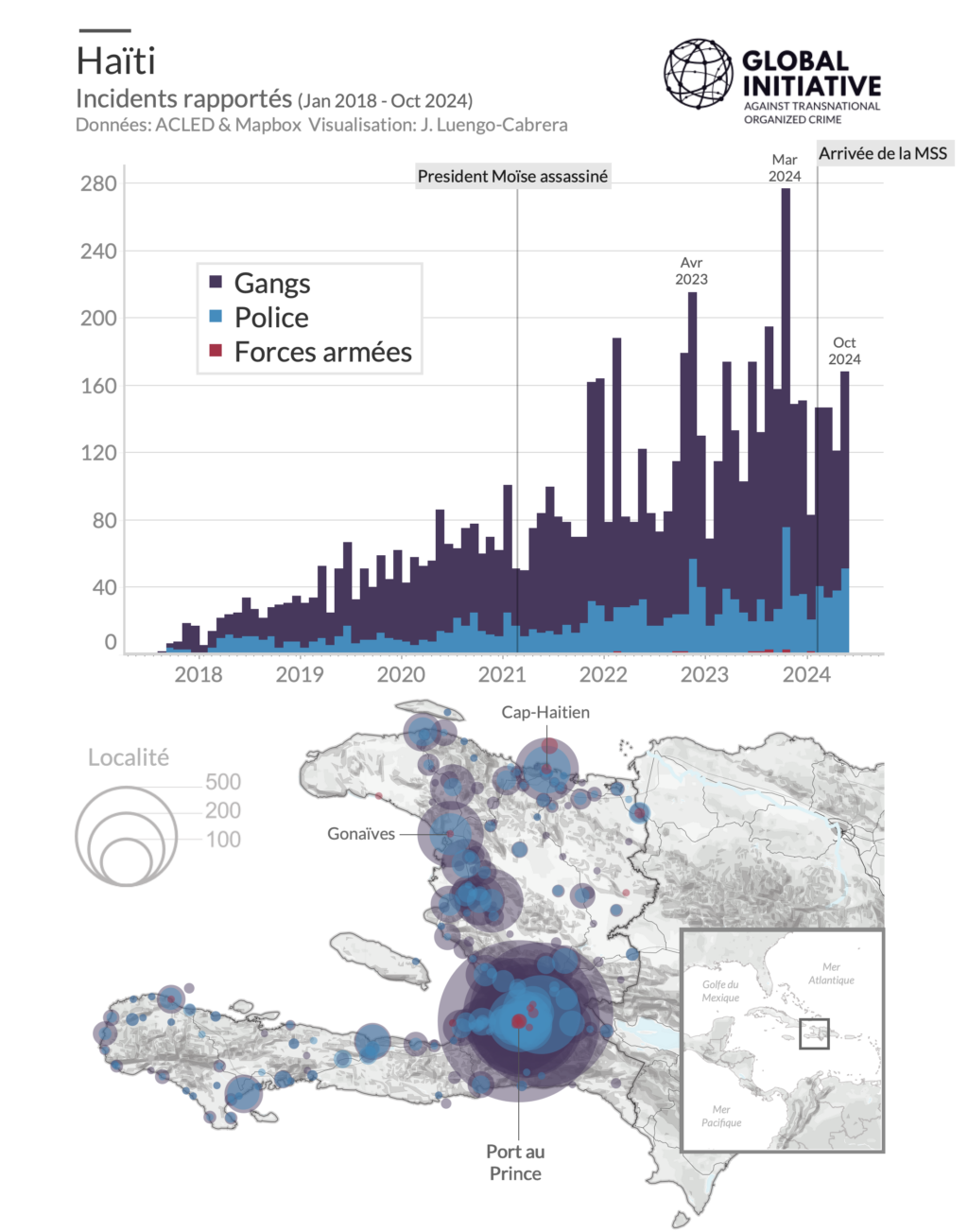

Haiti once again is being battered by a storm of violence. After a lull between May and September 2024, gang-related attacks have broken out again since October. This latest crisis, part of a year-long cycle of violence, is linked to fractious political developments and serious issues with the country’s public security strategy.

The attacks of recent weeks show it is the gangs, not the state, that are setting the security tempo, as power struggles between the country’s two heads of power – the Transitional Presidential Council on the one side and the government on the other – show the authorities are failing to get to grips with the situation. The criminal groups have taken advantage of institutional collapse and the political vacuum to extend their territorial and governance capabilities. The country’s sovereignty is increasingly shared between public authorities and gangs.

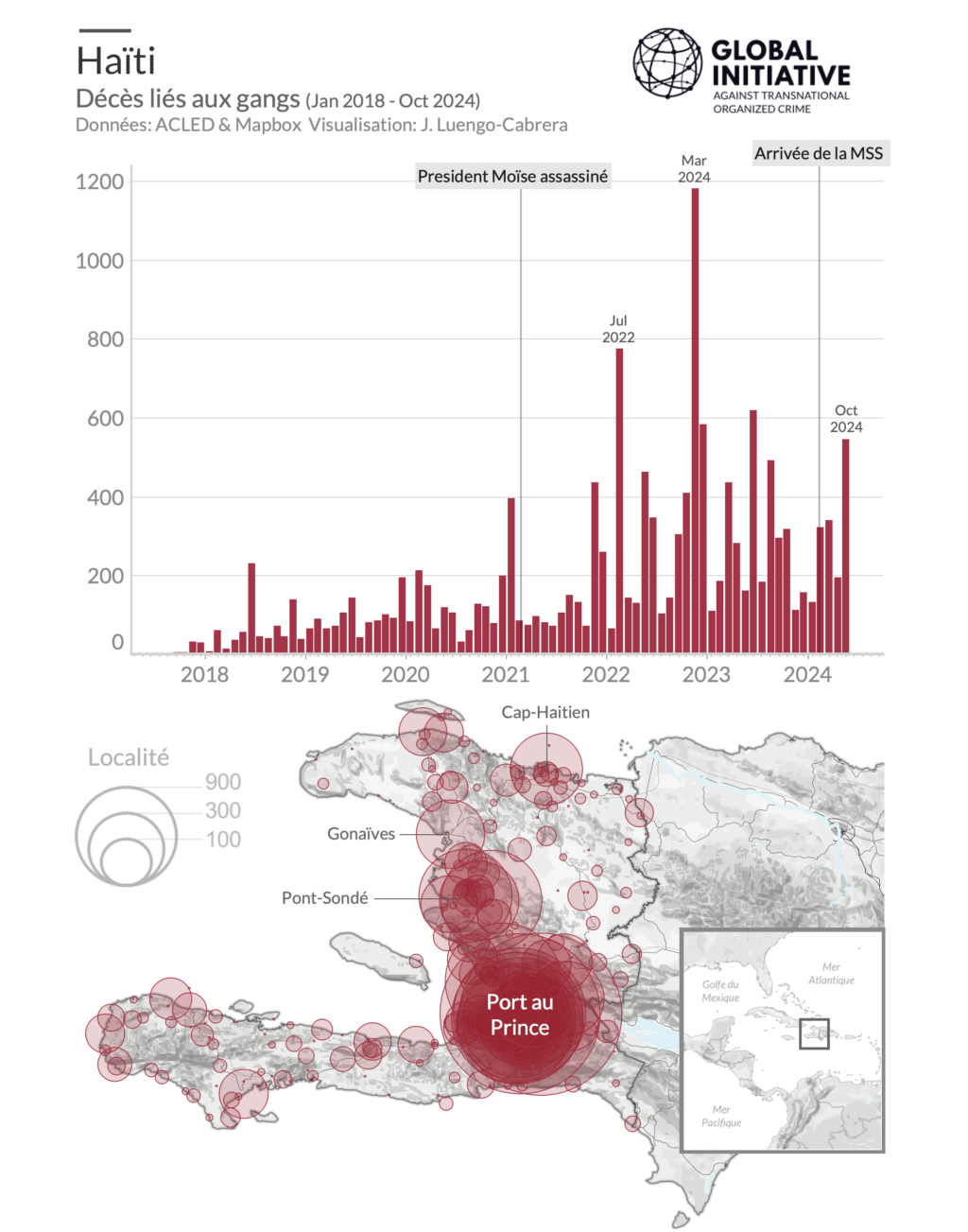

Between May and September, entente between the main gangs led to an uncomfortable truce, a decline in clashes between them and against the police, and a marked drop in the number of murders. But the relative calm was shattered by a massacre committed by the Gran Grif gang on 3 October in the Artibonite region. Apparently launched in retaliation against the population’s attempt to organize against extortion, the largest massacre in the country’s recent history opened a new cycle of violence. Since then, gangs, who are still united in the Viv Ansanm (Living Together) coalition, have resumed offensives in and around the capital, Port au Prince, and further afield in a bid to control strategic land and sea routes, including towards the Malpasse border crossing with the Dominican Republic.

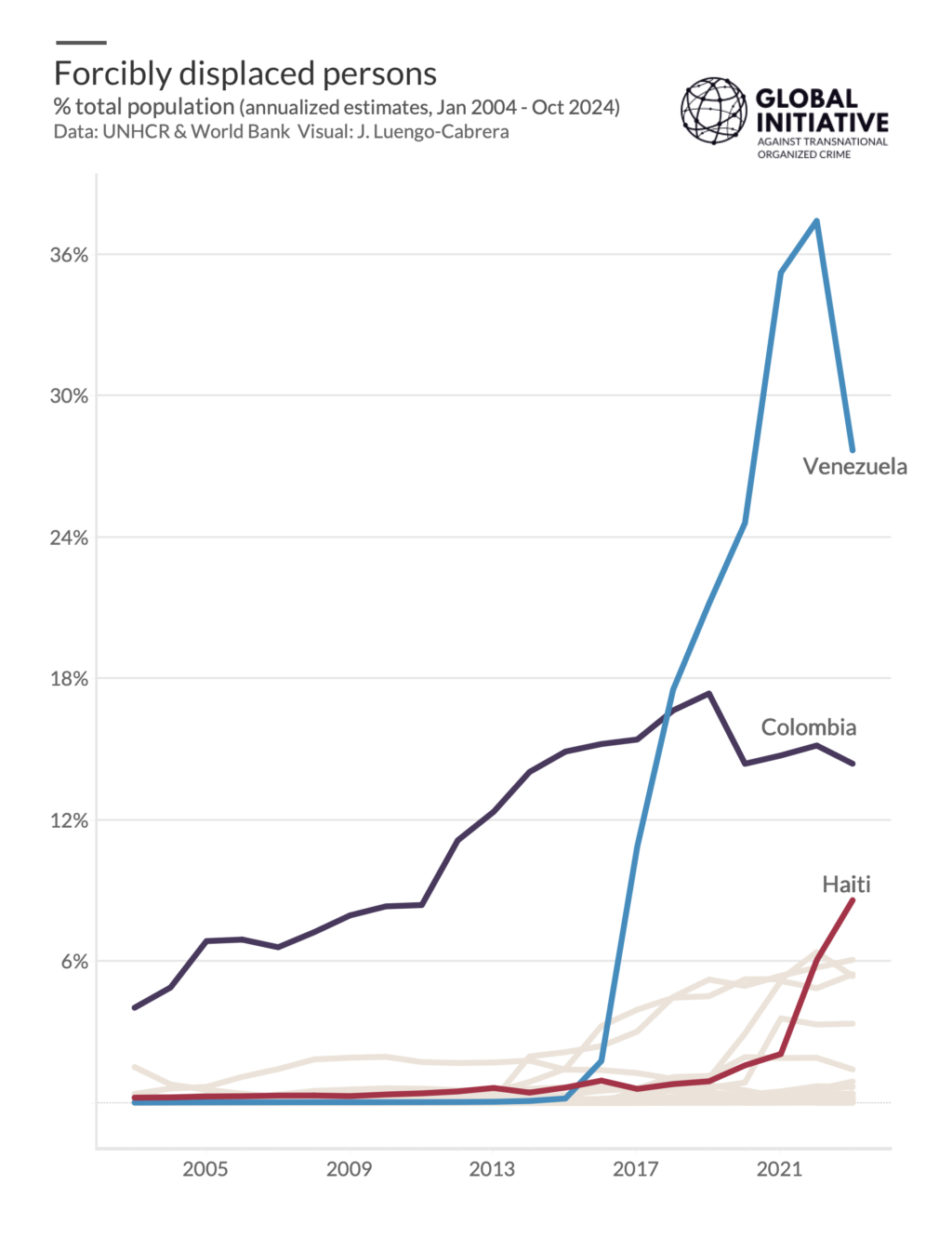

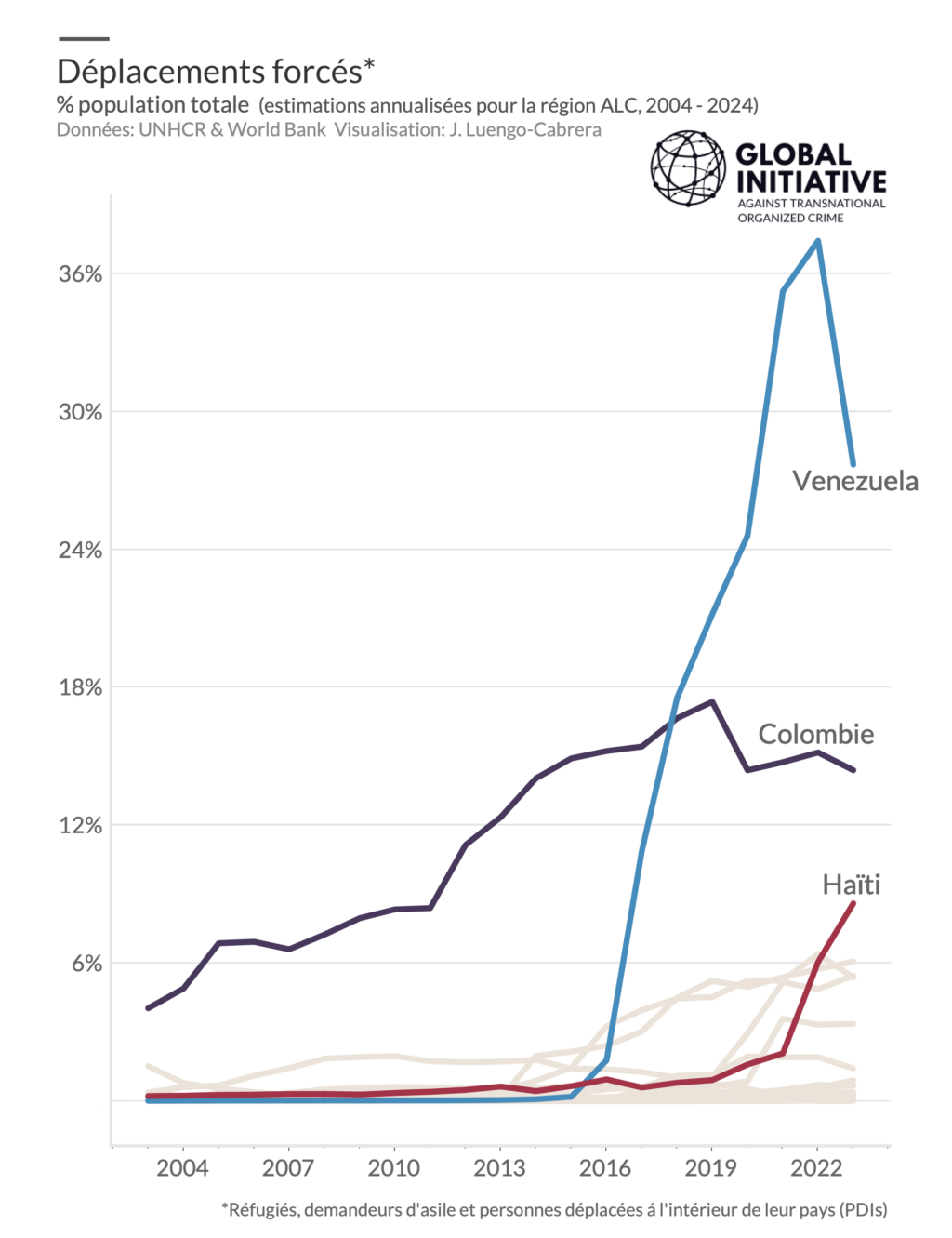

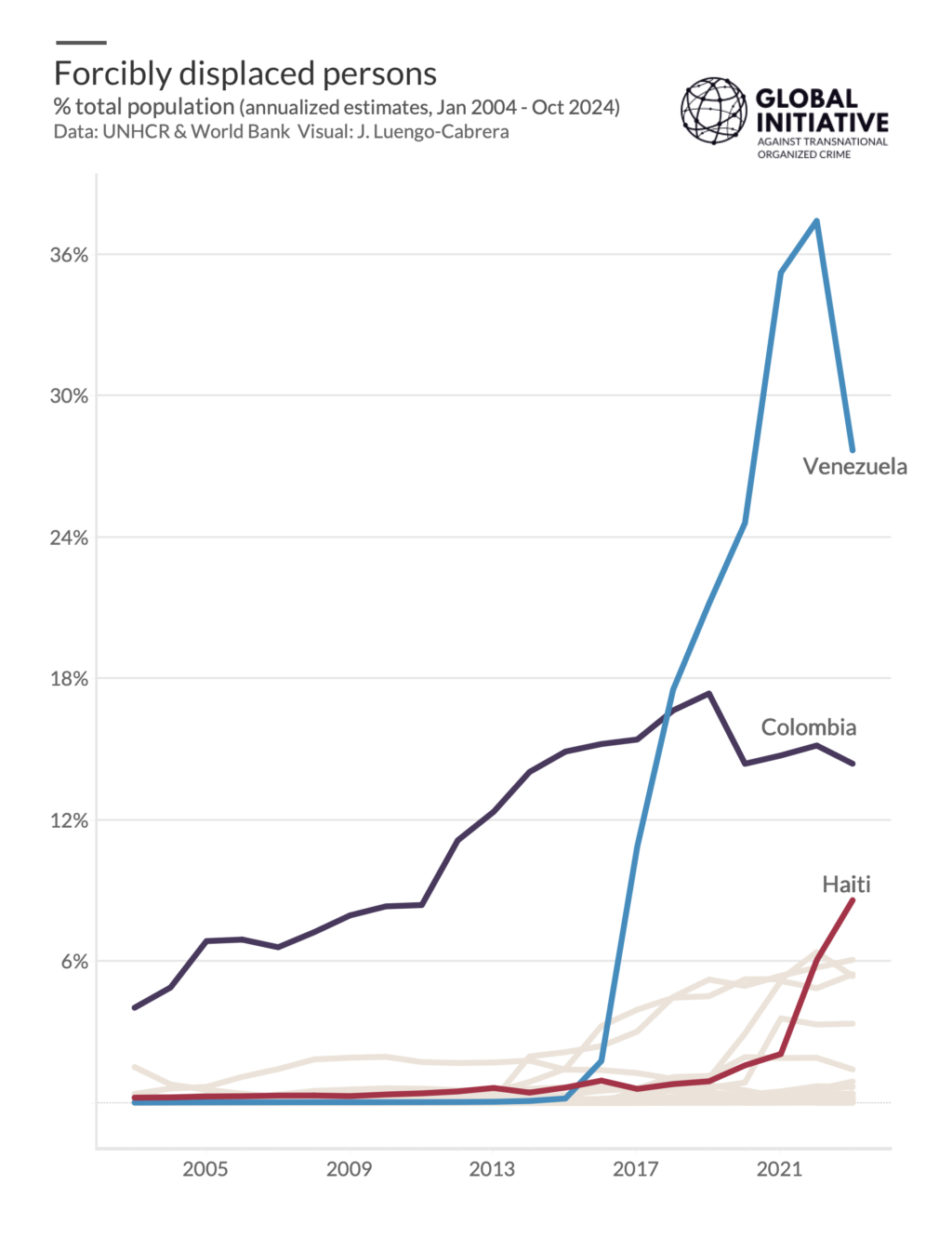

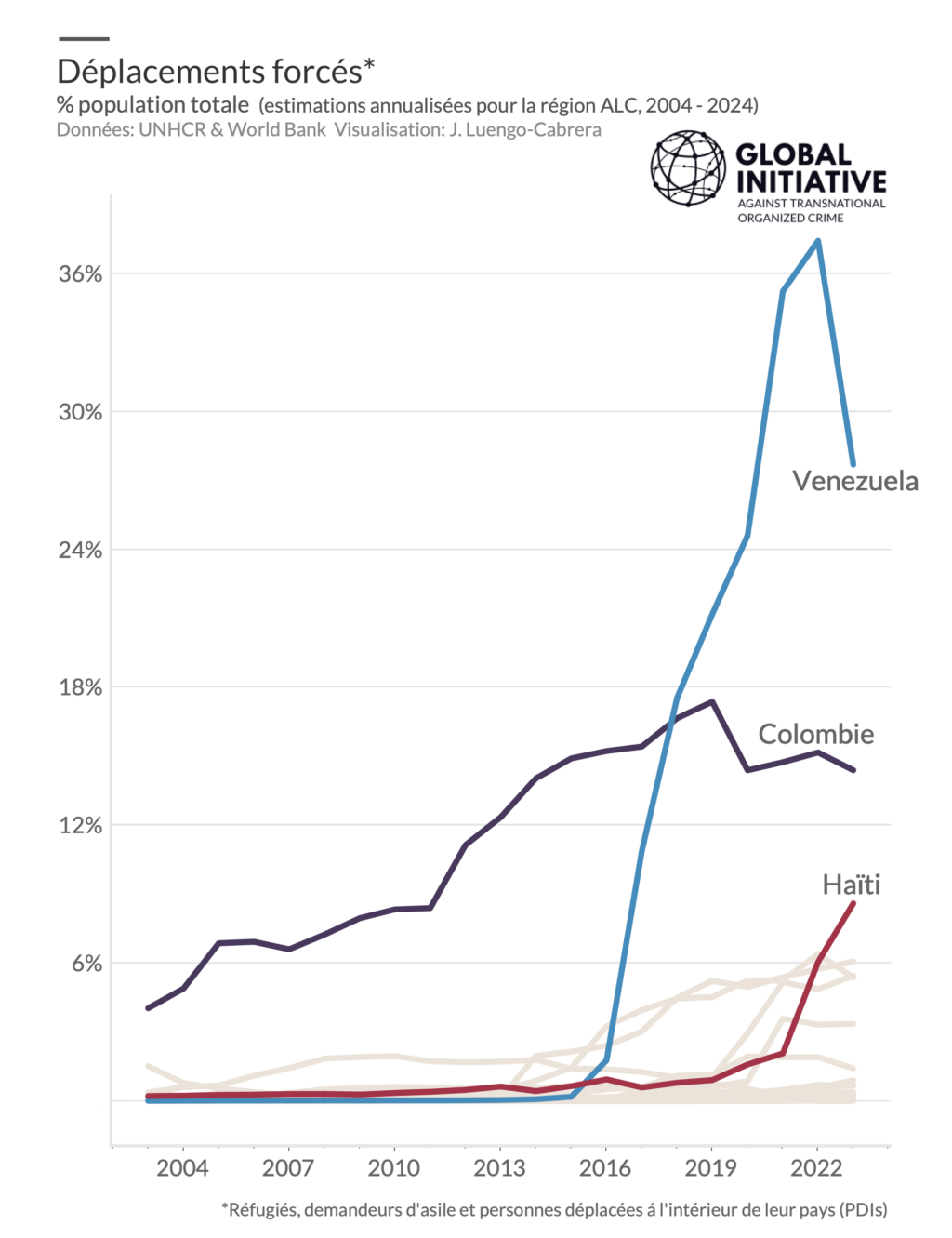

The recent attacks are estimated to have displaced some 40 000 people in the capital since 11 November – the largest forced displacement since UN Migration began tracking data in the country.

The gangs have recently taken territorial control of Solino and the commune of Pétion-Ville, a turning point in their strategy. Solino, a district in the centre of the capital, had resisted the gangs for over a year, thanks to collaboration between the Haiti police and vigilante brigades. Pétion-Ville is the heart of political, economic and international power in Haiti. Gang shootouts just metres from the residences of ambassadors and ministers, and the offices of international organizations show the gangs can attack wherever they please.

A political pyrrhic victory

The resumption of gang attacks coincides with a parallel political conflict that has been brewing since August between the Transitional Presidential Council and Prime Minister Gary Conille, culminating in Conille’s dismissal on 11 November and his replacement by Alix Didier Fils-Aimé.

Fuelled by personal wrangling and political party battles, the latest rift is further evidence of the fragility of the two-headed structure of Haitian governance. The Council’s rotating president, Leslie Voltaire, was installed in October during an investigation into three of the Council’s members for abuse of office and corruption. Voltaire managed to cling on and cement his position as head of state. But, for the political leaders, it is a Pyrrhic victory: Voltaire and the Transitional Presidential Council now reign over a mountain of ashes. Eight months after its establishment, the Council has not finished forming the Electoral Council, nor made any tangible progress in constitutional reform, which lie at the heart of its mandate. Meanwhile, the new Fils-Aimé government is not yet fully operational.

Equally disconcerting is the apathetic response of the authorities in the face of the recent eruption in violence. As politicians watch things unfold from the sidelines, it reinforces the impression of an institutional and political vacuum. It also bolsters gang leaders’ bravado. Jimmy Chérizier, the spokesman for Viv Ansanm, ridiculed the impotence of the Haitian authorities and the international community, and called for the downfall of the Transitional Presidential Council.

Failing response from the state

Despite some gains made by the police and the Multinational Security Support Mission, a police force approved by the UN Security Council in 2023, the resources are not sufficient to regain control of governance from the gangs. The Mission’s funding currently stands at US$96 million, woefully short of the estimated US$600 million needed to fulfil its operations. This has delayed the arrival of hundreds of additional Kenyan police agents, trained and on standby to leave Nairobi since October.

It is difficult to identify any meaningful inroads on the part of law enforcement, who are outnumbered and outgunned by the criminal groups, whose knowledge of the terrain and ability to open up multiple fronts simultaneously give them tactical advantage. Gangs now control 85% of the capital, no key gang-held territory has been retaken and no criminal leader has been arrested. Gangs and public forces hound each other, but the police do not seem to have the capacity to penetrate or occupy disputed areas over the long term.

In recent months, public debate has focused on the need to beef up capacity of the police and Multinational Security Support Mission with better equipment, such as drones and helicopters. But the most sophisticated armoury will not compensate for the lack of boots on the ground and serious deficits in police intelligence.

To make matters worse for the state, there have been reported incidents of abuses committed by Haitian police officers. International medical organization Doctors Without Borders (MSF) suspended its activities in Haiti on 19 November citing threats and acts of violence attributed to police officers and vigilante brigades against the medical charity’s staff and patients.

These incidents raise questions about the blurring of lines between police and vigilante groups. The number of vigilante units, which have replaced police security in dozens of neighbourhoods in Port-au-Prince, has skyrocketed this year. The anti-gang vigilante brigades on the streets of Haiti personify citizens’ eroded trust in the ability of state law enforcement agents to deal effectively with the gang violence. It is alarming that, in recent months, the government and police service have extolled the merits of what they describe as a mariage police-population (a marriage between the police and the people) and have called on the citizenry to support law enforcement. It is a chillingly dangerous dynamic, considering that many of today’s gangs started out as vigilante groups, and one that sends the message that the state and its police are not able to provide public security. With the development of vigilante brigades, in addition to the gangs’ increasing territorial fragmentation, Haiti is witnessing a situation where armed militia-type actors are multiplying and increasingly taking control of governance functions.

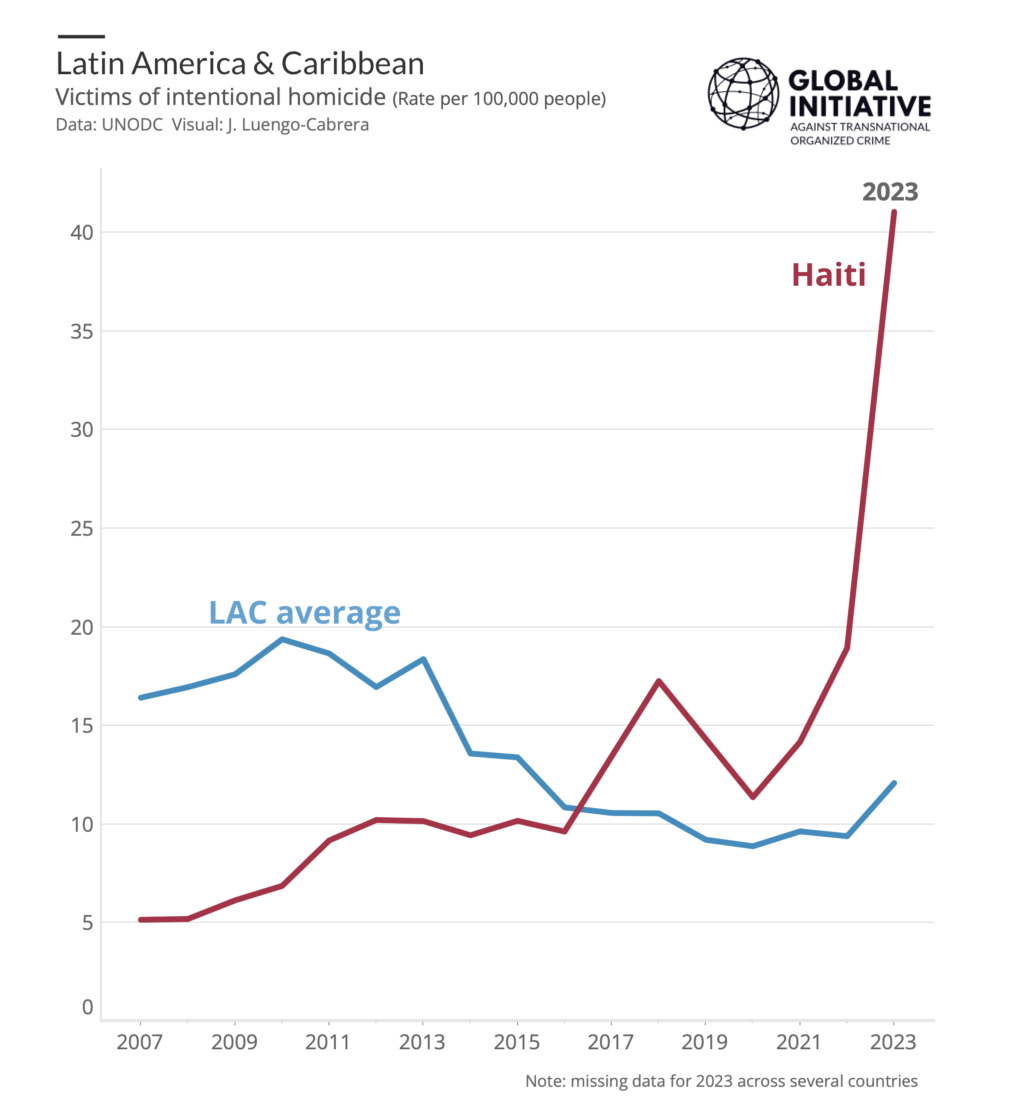

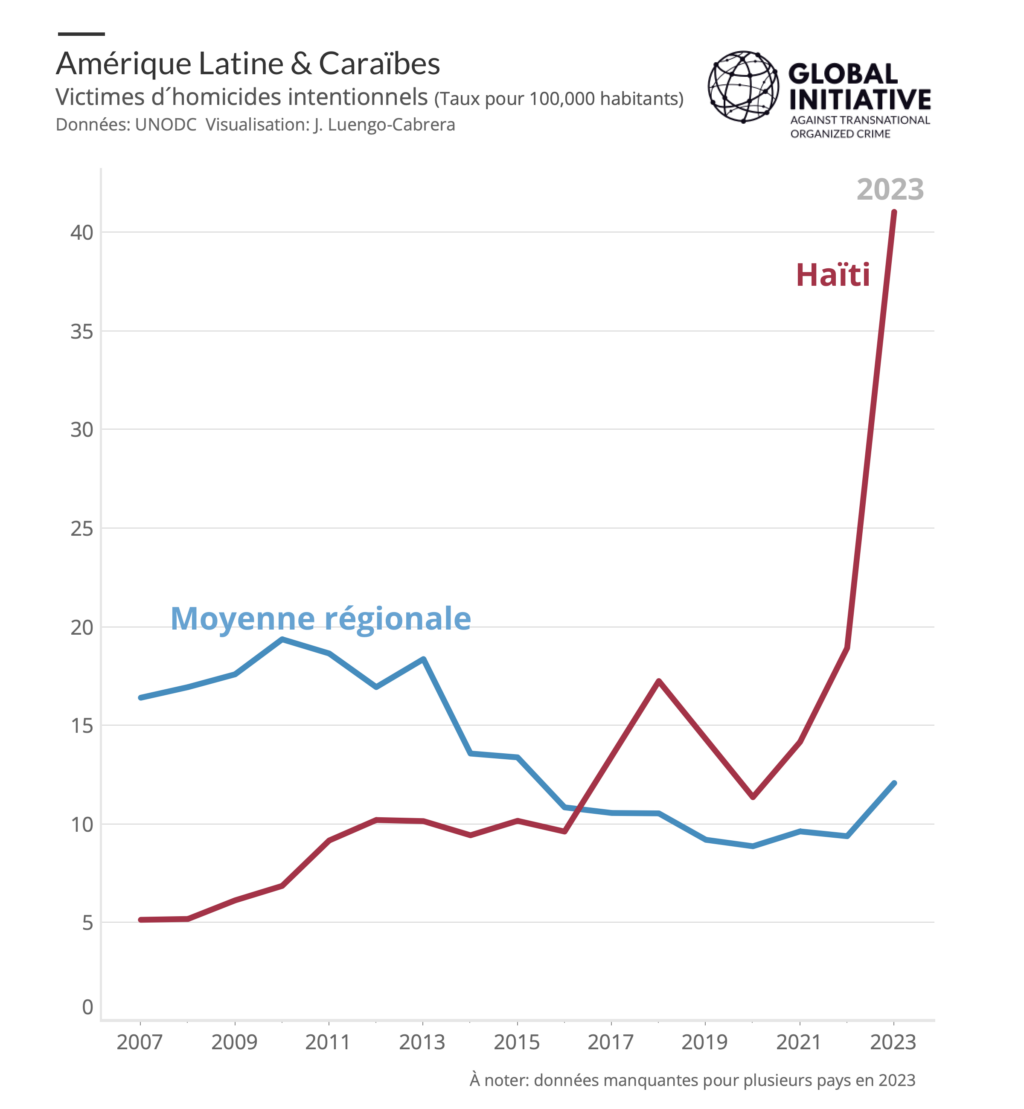

In a political-institutional vacuum, the gangs have weaponized violence to exert pressure on the system. The death toll in Haiti this year includes 4 544 homicides. Meanwhile the constitutional and electoral deadlines recede into the distance. There is an urgent need to establish a clear line of state governance and strategy that will restore at least a modicum of certainty and institutional continuity for the country. The international community must solve a complicated equation, which goes even further than the possibility of deploying a peacekeeping operation. Haiti needs urgent support now and on an enormous scale.

To receive monthly updates about the Haiti Observatory, please subscribe to our mailing list and get the latest information delivered straight to your inbox.

Haïti, entre la paralysie politique et l’escalade de la violence.

Haïti est à nouveau frappé par une tempête de violence. Après une période d’accalmie entre mai et septembre 2024, des attaques liées aux gangs ont éclaté depuis le mois d’octobre. Cette nouvelle crise, qui s’inscrit dans un cycle de violences qui dure depuis plusieurs années, est alimentée par la fragilité de la transition politique et à de graves problèmes liés à la stratégie de sécurité publique.

Les attaques de ces dernières semaines montrent que ce sont les gangs, et non l’État, qui dictent le tempo en matière de sécurité, alors que les luttes de pouvoir entre les deux institutions à la tête du pays – le Conseil présidentiel de transition d’une part et le gouvernement d’autre part – montrent que les autorités ne parviennent pas à maîtriser la situation. Les groupes criminels ont profité de l’effondrement institutionnel et du vide politique pour étendre leurs capacités territoriales et de gouvernance. La souveraineté du pays est de plus en plus partagée entre les pouvoirs publics et les gangs.

Entre mai et septembre, l’entente entre les principaux gangs a conduit à une trêve inconfortable, à une diminution des affrontements entre eux et contre la police, et à une baisse sensible du nombre de meurtres. Mais ce calme relatif a été rompu par le massacre commis par le gang Gran Grif le 3 octobre dans la région de l’Artibonite. Apparemment lancé en représailles contre la volonté de la population de s’organiser contre l’extorsion, le plus grand massacre de l’histoire récente du pays a ouvert un nouveau cycle de violence. Depuis, les gangs, toujours réunis au sein de la coalition Viv Ansanm (Vivre ensemble), ont repris leurs offensives dans et autour de la capitale, Port-au-Prince, et plus loin encore, pour tenter de contrôler des routes stratégiques maritimes et terrestres, notamment vers le poste frontière de Malpasse avec la République dominicaine.

Les récentes attaques ont entraîné le déplacement de quelque 40 000 personnes dans la capitale depuis le 11 novembre. Il s’agit du déplacement forcé le plus important depuis que UN Migration a commencé à recueillir des données sur le sujet dans le pays.

Les gangs ont récemment pris le contrôle de Solino et lancé des attaques contre la commune de Pétion-Ville, ce qui constitue un tournant dans leur stratégie. Solino, un quartier du centre de la capitale, avait résisté aux gangs pendant plus d’un an, grâce à la collaboration entre la police haïtienne et les brigades d’autodéfense. Pétion-Ville est le cœur du pouvoir politique, économique et international d’Haïti. Les fusillades entre gangs à quelques mètres des résidences des ambassadeurs et des ministres, et des bureaux des organisations internationales montrent que les gangs peuvent attaquer où bon leur semble.

Une victoire politique à la Pyrrhus

La reprise des attaques de gangs coïncide avec un conflit politique parallèle qui couvait depuis le mois d’août entre le Conseil présidentiel de transition et le Premier ministre Gary Conille, et qui a abouti au limogeage de ce dernier le 11 novembre et à son remplacement par Alix Didier Fils-Aimé.

Alimentée par des querelles personnelles et des affrontements entre courants et partis politiques, cette dernière crise politique est une nouvelle preuve de la fragilité de la structure bicéphale de la gouvernance haïtienne. Le président tournant du Conseil, Leslie Voltaire, a été installé en octobre, au plus fort d’une enquête contre trois membres du Conseil pour abus de pouvoir et corruption. Voltaire a réussi à s’accrocher et à consolider sa position de chef d’État. Mais pour les dirigeants politiques, il s’agit d’une victoire à la Pyrrhus : Voltaire et le Conseil présidentiel de transition règnent désormais sur une montagne de cendres. Huit mois après sa mise en place, le Conseil n’a pas fini de former le Conseil électoral, ni fait de progrès tangibles dans la réforme constitutionnelle, deux tâches qui sont pourtant au cœur de son mandat. Pendant ce temps, le nouveau gouvernement Fils-Aimé n’est pas encore pleinement opérationnel.

La réaction apathique des autorités face à la récente éruption de violence est tout aussi déconcertante. Et renforce l’impression d’un vide institutionnel et politique. Cela étaye également la bravade des chefs de gangs. Jimmy Chérizier, porte-parole de Viv Ansanm, a moqué l’impuissance des autorités haïtiennes et de la communauté internationale, et a appelé à la chute du Conseil présidentiel de transition.

Réponse inaudible de l’État

Malgré les progrès réalisés par la police et la Mission multinationale de soutien à la sécurité, une force de police approuvée par le Conseil de sécurité des Nations unies en 2023, les ressources ne sont pas suffisantes pour reprendre le contrôle aux gangs. Le financement de la mission s’élève actuellement à 96 millions de dollars américains, ce qui est très insuffisant par rapport aux 600 millions de dollars estimés nécessaires pour mener à bien ses opérations. L’absence de fonds retarde également l’arrivée de centaines d’agents de police kenyans supplémentaires, formés et prêts à quitter Nairobi depuis le mois d’octobre.

Il est difficile d’identifier des avancées significatives de la part des forces de l’ordre. Celles-ci sont toujours moins nombreuses et souvent moins bien équipées que les groupes criminels. De plus, la connaissance parfaite du terrain et la capacité des gangs à ouvrir plusieurs fronts simultanés, à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de zone métropolitaine de Port-au-Prince leur donnent un avantage tactique considérable. Depuis mars, les gangs contrôlent 85% de la capitale, tandis qu’aucun territoire clé tenu par les groupes criminels n’a été repris et aucun chef armé n’a été arrêté. Les gangs et les forces publiques se pourchassent et s’affrontent par vagues successives, mais la police ne semble pas avoir la capacité de pénétrer ou d’occuper durablement les zones contestées.

Ces derniers mois, le débat public s’est concentré sur la nécessité de renforcer les capacités de la police et de la mission multinationale de soutien à la sécurité avec différents équipements, tels que des drones et des hélicoptères. Mais l’arsenal le plus sophistiqué ne compensera pas l’absence de personnel en nombre suffisant et les graves déficits en matière de renseignement policier.

Pour aggraver la situation de l’État, des incidents ont été signalés concernant des abus commis par des officiers de police haïtiens. L’organisation Médecins sans frontières a suspendu ses activités en Haïti le 19 novembre, invoquant des menaces et des actes de violence attribués à des policiers et à des brigades d’autodéfense à l’encontre du personnel et des patients de l’organisation médicale.

Ces incidents soulèvent des questions sur l’effacement des frontières entre la police et les groupes d’autodéfense. Le nombre d’unités d’autodéfense, qui ont remplacé la sécurité policière dans des dizaines de quartiers de Port-au-Prince, est monté en flèche cette année. Les brigades d’autodéfense dans les rues d’Haïti illustrent la perte de confiance des citoyens dans les forces de l’ordre pour lutter efficacement contre les gangs. Il est également alarmant de constater que, ces derniers mois, le gouvernement et les services de police ont vanté les mérites de ce qu’ils décrivent comme le mariage « police-population » et ont appelé les citoyens à soutenir les forces de l’ordre.

Il s’agit d’une dynamique dangereuse, si l’on considère que de nombreux gangs actuels sont nés de groupes d’autodéfense, et qui envoie le message que l’État et sa police ne sont pas en mesure d’assurer la sécurité publique. Avec le développement des brigades d’autodéfense, en plus des gangs et de la fragmentation territoriale croissante, nous assistons à un processus de « militianisation » de la violence, dans le sens de la multiplication des acteurs armés opérant dans le pays et assumant des fonctions de gouvernance de plus en plus larges.

Dans un climat de vide politico-institutionnel, les gangs utilisent de nouveau la violence comme arme politique pour exercer leur pression sur le système. Cette année, 4 544 homicides ont été recensés en Haïti. Pendant ce temps, les échéances constitutionnelles et électorales s’éloignent. Il est urgent d’établir une ligne claire de gouvernance qui rétablira au moins un minimum de certitude et de confiance institutionnelle pour le pays. De son côté, la communauté internationale doit résoudre une équation complexe, qui va même au-delà de la possibilité de déployer une opération de maintien de la paix. Quoi qu’il en soit, Haïti a besoin d’un soutien urgent et à grande échelle.