Posted on 09 Jun 2023

In May 2022, two Nigerian citizens were arrested in Niamey, Niger, while trying to drive back to Nigeria in a stolen Toyota Corolla. The Corolla had a Nigerian licence plate, but police discovered that the car had recently been stolen from a Nigerien police officer.

Fake military identification cards, and another Nigerian licence plate, were found in the car. The men were posing as Nigerian military officers. One had in fact been a former officer but was discharged in 2017 for desertion, and the other worked for Nigeria’s correctional service. After an investigation, it transpired that the men had left Nigeria three days before the arrest, and they had driven to Niamey in a stolen Toyota Hilux. The car, stolen in Nigeria, was resold in Niamey with the assistance of a Nigerien accomplice who was later arrested. It appears that this accomplice was also involved in the theft and resale of motorbikes, and possibly of other illicit commodities such as weapons. He was found with three AK-47 rifles and 151 cartridges, along with a stolen motorbike, other motorbike parts and three wristwatches.

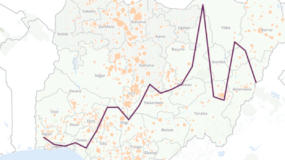

This example showcases many of the dynamics of car theft in the central Sahel region. In particular, it shows how borders are exploited by car thieves to evade law enforcement. Here, the central Sahel refers to Mali, Burkina Faso and the western part of Niger, specifically the provinces of Tillabéri and Tahoua. In this instance, cross-border cooperation between security services led to an arrest. However, car theft networks realize this is still rare, and so persist with cross-border activities to mitigate risks of detection. Given that cars are in demand and easy to resell, and can be used as a mode of transporting other goods, actors operating in the vehicle theft market often diversify across other illicit economies. Individuals with low-level official contacts, or histories of working with the state, may exploit their knowledge and contacts to produce counterfeit paperwork.

However, the implications of the stolen vehicle trade in the central Sahel are more significant than a single case may suggest. The 2012 crisis in northern Mali, its aftermath and the regional spread in the ensuing decade have contributed to ongoing violence in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and increasingly at the northern edges of West African coastal nations. Although road users in the central Sahel endured criminal behaviour and insecurity long before the onset of the present conflict, much of the current insecurity on the roads of the central Sahel is symptomatic of the conflict that has developed over the past decade. Vehicle theft is only one aspect of the insecurity experienced on roads. Robberies of passengers and their belongings, violent interrogations, abductions or killings by armed groups, as well as severe road accidents, are all unfortunately commonplace.