Posted on 13 Mar 2020

The 63rd session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) took place in Vienna (2–6 March), albeit with some slimmed down delegations due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The agenda was also slim: only five resolutions were tabled and adopted (a much lower number than in recent years). The major outcome was that member states opted again to postpone until December 2020 a vote on changing the status of cannabis. The changes, recommended by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Expert Committee on Drug Dependence in January 2019, would remove cannabis from the category reserved for the most dangerous substances. Although there has still been no decision reached on a way forward, the implications of any changes that may be adopted will be unpredictable in terms of how they may affect illicit markets.

Despite the

depleted turnout, there was a wide range of well-attended side events on a

plethora of drug-related issues, including some with a strong focus on

organized crime. The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC)

took an active role by co-organizing two side events. At these, we highlighted

the changing nature of drug trafficking and use in Africa, and the benefits of

engaging with the communities affected by drug trafficking. (Click here to see the gallery of photos of the GI-TOC

events.)

What next for cannabis?

As the GI-TOC

highlighted in June 2019, cannabis classification continues to be the

political hot potato of the international debate on drugs policy. The topic has

been brought into sharp focus at the CND recently, especially since the

legalization of the recreational use of cannabis by Canada, which came into

force in October 2018, and the 2019 WHO committee recommendation to remove

cannabis from the category of substances considered the most dangerous (specifically,

to remove cannabis and cannabis resin from Schedule IV

of the 1961 Convention). The

WHO recommendations also propose simplifying how cannabis is classified by

adjusting the status of some cannabis-derived substances (including cannabidiol

(CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)). The implications of such decisions would

have potentially considerable effects on the global illicit and licit markets

for cannabis and cannabis products. Following previous decisions from the CND

to delay a vote on the changes, the member states this time opted to:

‘… continue …

the consideration of the recommendations of the WHO on cannabis and

cannabis-related substances, bearing in mind their complexity, in order to

clarify the implications and consequences of, as well as the reasoning for

these recommendations, and … to vote at its reconvened 63rd session in December

2020, in order to preserve the integrity of the international scheduling

system.’

Diplomats

involved in the discussions believe the vote to remove cannabis from Schedule

IV of the 1961 Convention will be won, but the other votes on the cannabis

substances would be unclear. Either way, the votes taken in December (if they

do indeed take place then) will have practical and political ramifications. Those

member states voting against the reforms will be opposing the recommendations

of the independent scientific advice of the WHO and setting a precedent for

political priorities to take precedence over technical advice. Those advocating

for reform will need to ensure the public messaging clearly differentiates this

decision on downgrading the perceived danger of cannabis from the legalization

of the drug, which has already taken place in some countries and is definitely

not within the scope of the conventions (nor a recommendation of the WHO). The

road until the next decision point at the reconvened session in December is

short, and the decision taken then will have a major impact not only for

criminal economies, but also for health, security and development agendas

across the world. Member states and civil society therefore have a limited

opportunity to analyze the available evidence around crime, health and

development in order to make an informed

policy decision on the proposed reform.

What other

issues did the CND address this year?

The nature of

the CND’s role has evolved in recent years. Since the UN General Assembly

Special Session on the World Drug Problem (UNGASS 2016), the focus of the

commission has broadened out from the old ‘three pillar’ model (i.e. supply

reduction, demand reduction and international cooperation) to the ‘seven chapters’

of UNGASS, which include a stronger focus on issues like healthcare, human

rights, and access to medicines and development. This expanding remit was a

necessary step in moving towards a more holistic approach to tackling these

issues, but how did this year’s session reflect those changing priorities of

the international community?

The five

substantive resolutions tabled this year covered the following issues:

- Engaging with the private sector on supply reduction, tabled by Georgia, Honduras, Japan, Paraguay and USA (a group of countries with a traditional or conservative outlook on drug control). This resolution aims to encourage coordination between states and the private sector on supply-reduction approaches, including trafficking of synthetic drugs and precursors.

- Youth engagement in prevention, tabled by Azerbaijan, Belarus, Egypt, Guatemala, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines, Russian Federation, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela and Vietnam. This resolution can be seen as a traditional demand-reduction approach promoted by a group of countries with a traditional or conservative outlook to drug policy, to promote family- and youth-based prevention campaigns.

- Improving data collection and promoting evidence-based responses, tabled by Australia, Croatia – on behalf of the European Union (EU), Georgia, Honduras, Mexico, New Zealand and Norway. This group of countries, which have a largely pro-reform outlook on drug policy, tabled this resolution with a view to updating data collection and evidence processes, so they are more in line with the broader group of UNGASS priorities.

- Promoting access to controlled medicines, tabled by Argentina, Australia and Croatia (on behalf of the EU), El Salvador, Georgia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway and Paraguay. A varied group of countries in terms of policy position used this resolution to promote their common priorities on ensuring access to controlled substances, a sometimes overlooked aspect of the UN drug conventions.

- Alternative development and development-oriented drug-control policies, tabled by Chile, Colombia, Germany, Myanmar, Peru and Thailand. In recent years, there has tended to be a resolution dedicated to alternative development at every CND session (there is a chapter dedicated to it in the UNGASS outcome document). It is a prism through which development is often channelled in CND discussions, and something that is beginning to change through initiatives such as the Drugs and Development Hub, launched in Bogotá earlier this year.

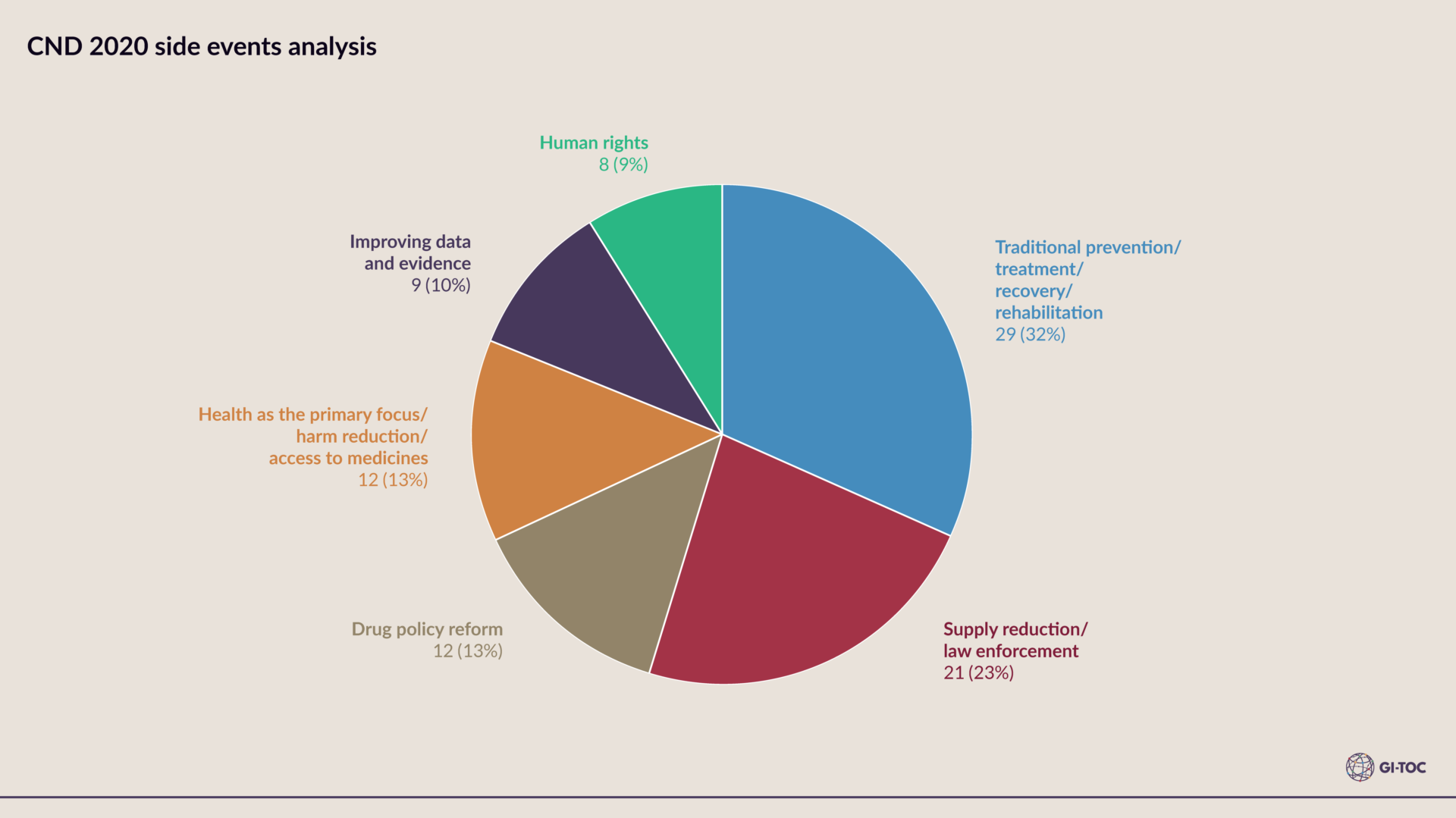

Outside of the formal agenda during side events that took place this year, a spread of issues were discussed, some related to the traditional areas of CND work, as well as newer issues coming out of UNGASS. A breakdown of the number of events dedicated to the most popular focus issues in the side event agenda is shown below:

The GI-TOC’s contribution

The GI-TOC focused its efforts on two interventions at the session.

Improving understanding of the political economy of drug

markets in Africa

The GI-TOC chose the CND to unveil its latest report on

heroin markets in East and Southern Africa – a publication of the EU-funded

ENACT programme (Enhancing Africa’s Response to Transnational Organized Crime),

in which the GI-TOC, the Institute for Security Studies and INTERPOL are

partners. Titled ‘From the Maskani to the Mayor’, this report, by Simone

Haysom, examines how heroin trafficking has shaped the growth of villages,

towns and cities along the Southern Route – a network that traffics Afghan

drugs across the Indian Ocean and through Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique to

South Africa. The report makes a series of recommendations on how to understand

drug markets, what law enforcement can do to better cooperate, how the markets

link to local and high-level corruption, what can be done to integrate marginalized

communities, how poor public transport systems contribute to the problem, and

what should be done to better counter the violence associated with the drug

trade.

The report was launched to a diverse and full audience in a

side event supported by the EU, and included discussion from the floor,

including expressions of support from an African Union representative. The report

will serve to enrich the debate around law enforcement, development and urban

violence in the African communities affected by the heroin trade.

Bridging the gaps between drugs, crime and development policy

The Drugs and Development Hub is a joint initiative of the GI-TOC, the GIZ Global Partnership on Drugs Policies and Development, the London School of Economics (LSE) and the Universidad de los Andes in Colombia. Following the launch event of the Drugs and Development Hub, in Bogotá in January 2020, the GI-TOC partnered with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), GIZ and LSE to promote the work of the Hub at the CND. The Hub aims to build bridges between the drugs, crime and development communities. In her opening remarks, Kristiina Kangaspunta, chief of the UNODC Crime Research Section, acknowledged the difficulties in coordinating between the CND and the UNODC’s Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, and said she hoped the Hub would help address this. The GI-TOC is contributing to the Hub by providing insights and connections from its Resilience Fund, which supports community actors who are building local resilience against organized crime, and we also look forward to supporting increased engagement with development actors through the Hub.