Posted on 28 Oct 2015

In the second edition of Atlantic Currents, a publication by the George Marshall Fund (GMF), builds on the previous one in seeking to develop a deeper understanding of the history and trends that shape the societies bordering the Atlantic Ocean. Many of those trends are driven by powerful new flows of goods, ideas, people, and conflict that traverse these societies and their shared ocean.

As can be seen in this volume and other research on the Atlantic space, there are numerous current transnational challenges and opportunities that could be better understood from a systems perspective that focuses on structure, interaction, flows, and multiple causes. Understanding the component parts of a system remains important, but zeroing in too closely on the pieces can blind analysts and policymakers to the broader dynamics at play that constrain and enable certain outcomes.

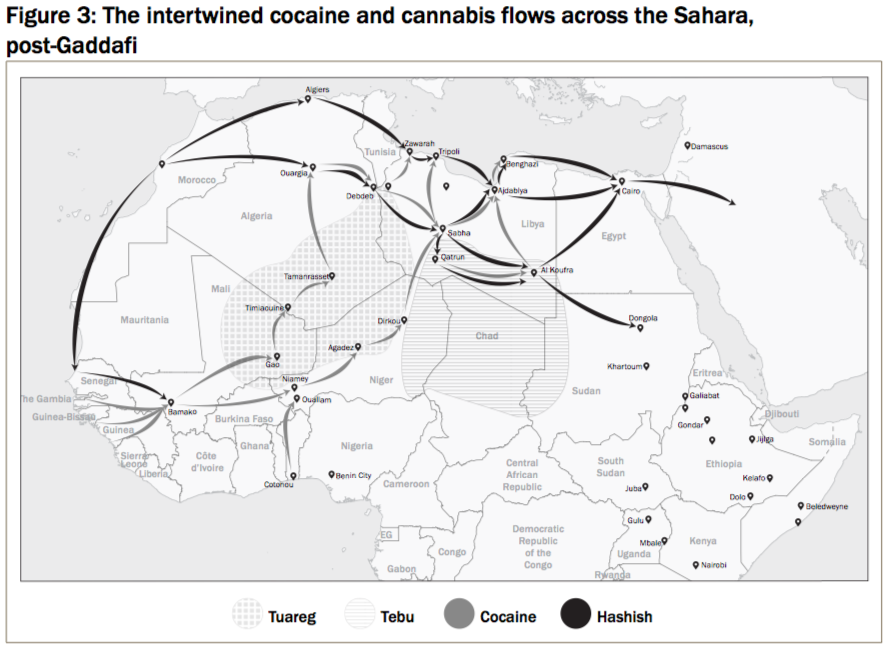

In terms of systemic challenges, Tuesday Reitano and Mark Shaw of the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, demonstrate in the chapter, “Atlantic Currents and their Illicit Undertow: Fragile States and Transnational Security Implications”, how drug and migrant trafficking routes through the Greater Sahara today flow across porous borders of weak states based on certain patterns that date back centuries and that are linked to the ethnic Tebu and Tuareg nomadic groups that span several states.

We compare the impact of two illicit flows across the Sahara: drug trafficking, particularly the cocaine flow from Latin America through West Africa toward Europe, and the emerging and increasingly virulent migrant smuggling trade from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe. Both of these flows have differing degrees of entrenchment and social acceptance in the fabric of the Saharan states, and consequently, their impact on regional geo-politics, the community, and stability both at home and abroad has been different. While not exclusively to blame for conflicts in Mali, Libya or in the wider Sahara, the presence of these flows is shaping the political economy of instability in two ways: by eroding already dysfunctional states through corruption and collusion, and by strengthening their armed counterparts who have sought to “tax” the trade.

Both of these flows are increasingly having transatlantic implications as, ironically, Europe and North America are the primary destination markets for the majority of illicit flows in the Greater Sahara and yet the states through which these flows transit have become an important driver of instability on the European periphery. The nature of illicit trade is such that it is almost impossible to counter without effective state counterparts in the region, and the military interventions that are often the preferred response are poorly placed to achieve impact and they instead exacerbate social tensions. The result has been new forms of hybrid governance and the breakdown of colonial boundaries.

This chapter illustrates the detrimental impact of illicit economies on efforts toward peacebuilding and state consolidation, and discusses the rise of extremist ideologies. These are arguably the most significant developments in the Greater Sahara region since the end of colonial rule, and in an age of globalization, they are intimately connected to the drug consumption and labor habits of the former colonial powers themselves.