Posted on 02 Feb 2026

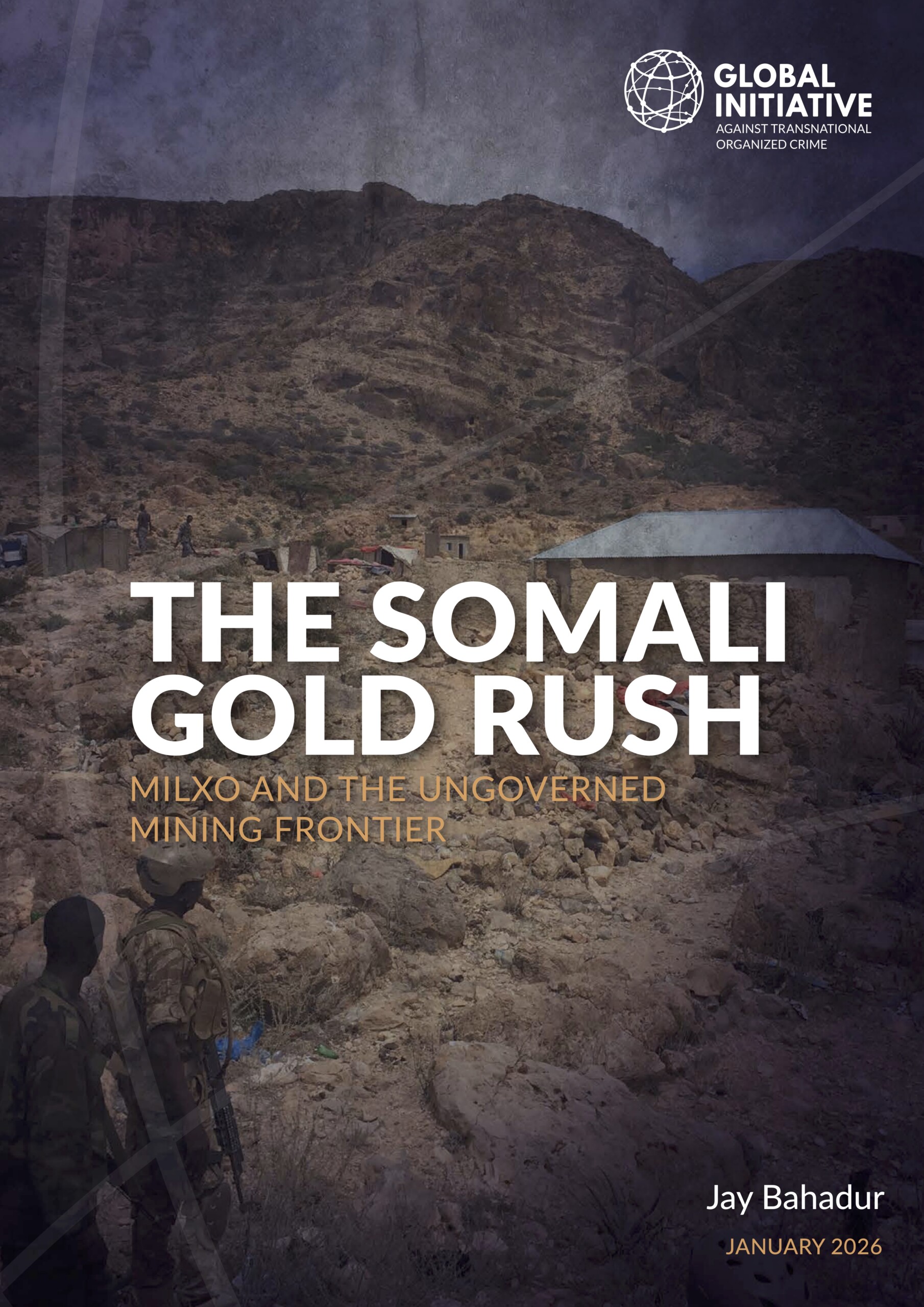

Milxo is a tiny mining settlement in a remote and contested region of north-eastern Somalia that, over the past decade, has become the site of one of Africa’s least-known gold booms. What was little more than a cluster of structures housing a few hundred people in 2016 has expanded into a sprawling settlement of an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 residents, drawing prospectors from across Somalia and from abroad, including Sudan, Yemen, Tanzania and Ethiopia. This rapid growth has brought new livelihoods to a neglected region, but it has unfolded in a legal and political vacuum marked by contested sovereignty, weak governance and insecurity.

Milxo lies in a region claimed at various times by Puntland, Somaliland and the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), and more recently by the SSC-Khatumo administration, which received formal recognition from the FGS in 2023. No authority exercises effective control over the area. Local miners describe Milxo as a ‘free zone’ in which no authority regulates extraction, issues licences or enforces taxation. As a result, gold mining has developed without a codified legal framework, with Puntland lacking a functioning extractives regime and the FGS maintaining that mining activity in Milxo is illegal under federal law.

Within this vacuum, a fragmented and unregulated mining economy has emerged. Field research documented 20 mining sites operated by at least 18 commercial entities, many employing foreign technical workers and using rudimentary and hazardous extraction methods, including widespread mercury use and cyanide leaching plants. Very few of these operators appear to hold licences from Puntland authorities, and Puntland has no binding mining law in force. The only identifiable state revenue from the gold trade is a nominal customs levy collected at Bosaso airport, representing a fraction of potential income and often absent from official accounts.

The absence of regulation has created conditions conducive to elite capture and armed-group exploitation. Evidence collected by the GI-TOC indicates that at least one major operator is linked to Puntland’s president. Al-Shabaab, which maintains a presence in the nearby Golis Mountains, has repeatedly attempted to tax or infiltrate mining operations. While the extent of revenue derived from gold is contested, phone records and eyewitness accounts indicate ongoing extortion activity, often framed as zakat.

Milxo’s gold enters the global supply chain with minimal scrutiny. Almost all exports flow to Dubai, typically carried by couriers on commercial flights. Reported imports of Somali gold into the United Arab Emirates have nearly doubled since 2017, rising from 2.8 tonnes to more than five tonnes in 2023. Despite recent regulatory changes, enforcement appears uneven, and couriers report that documentation on origin or compliance is rarely requested.

This report traces the evolution of the Milxo gold rush, documents mining practices, maps supply chains from mine to market, and examines how unregulated extraction intersects with elite networks, armed groups and Somalia’s incomplete federal system. It provides the first comprehensive assessment of how an ungoverned goldfield in northern Somalia has become embedded in the global gold market.