Posted on 11 Oct 2024

On 12 September 2024, the Nigerian military killed Kachalla Halilu Sububu, a notorious bandit leader in Zamfara state in north-western Nigeria, and several of his senior commanders in an ambush. Although previous reports of Nigerian bandit leaders’ deaths – such as those of Kachalla Turji and Dogo Gide – have often turned out to be false, Sububu’s death has been confirmed in a statement by the military.

This operation highlights the potential rewards and risks of law enforcement targeting senior bandits. Sububu’s killing may be a win for the state by ending his reign of terror, but it could also trigger an upsurge in violence and instability as rival factions scramble to vie for control over the lucrative revenue streams generated by the wealthy Sububu and his band, leading to heightened risk of attacks on communities.

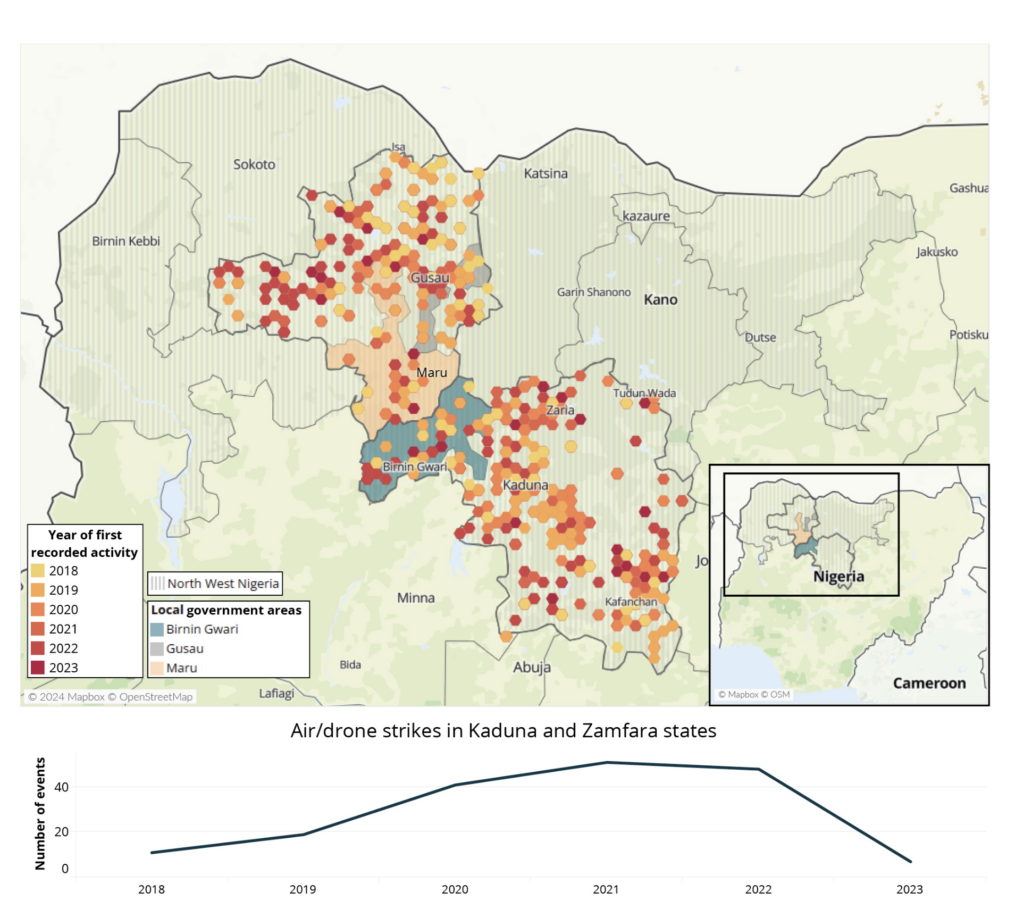

Since 2011, Nigeria’s North West region has been plagued by rural banditry, a brutal enterprise involving cattle rustling, kidnappings and large-scale assaults on communities. Since 2022, it has been estimated that these activities led to at least 4 000 deaths. In April 2024, the International Organization for Migration reported that there were over 1.3 million internally displaced persons in the country’s North West and North Central regions. Most of this displacement is linked to instability fuelled by banditry-related violence.

The diversity of Sububu’s illicit activities – from cattle rustling to kidnapping to gold mining – reflects how banditry in north-west Nigeria has developed over time. Initially involved in cattle rustling, he shifted his focus to kidnapping and arms trafficking in 2019. And by 2022, he had established himself as the bandit leader with the biggest share of gold mines under his control.

The bandit leader’s activities in the gold mines mirror broader regional trends. His initial approach involved violent raids to seize gold and valuables from miners. But by 2022, he moved on to imposing taxes on miners and eventually gained full control of several mines, using both forced and paid labour. By late 2023, he had also become the largest arms supplier to other bandit leaders.

Sububu, who travelled with a large entourage of about 200 people on motorbikes, controlled roughly 1 000–1 200 men spread across 15 camps in Zamfara, Kaduna and Katsina. His death, along with 56 others, including a number of senior figures in his group, makes a succession contest likely and could lead to the group’s splintering.

His younger brother Mati has reportedly taken control of several mining sites in Zamfara. However, it is unclear whether Mati can maintain control of the mines, or for how long. Sububu was far more well-connected, feared and respected in bandit circles – factors that helped him fend off competition and maintain a firm grip on the mines he controlled.

The more fragmented banditry landscape that may ensue following his death could lead to an increase in infighting. Competition is likely to be particularly intense around the gold mines previously controlled by Sububu in Zamfara, with implications for the stability of surrounding communities. The taxation system he imposed in 2022 could be disrupted, leading rival groups to revert to robbing miners, as was the case when Sububu’s group first took control of the mines. This would damage relations between mining communities and Sububu’s group, who had reached a fragile truce in recent years, allowing mining activities to continue relatively unimpeded. Nevertheless, local communities have celebrated his killing, pointing to the unpopularity of bandit groups.

Besides the gold mines, the arms market in the North West is likely to be affected as other bandits seek to follow in Sububu’s footsteps and take advantage of the lucrative arms trafficking trade. Bandit kingpins such as Dogo Gide and Turji are well connected and have the ability to take over the arms trade.

However, the killing of Sububu and several of his commanders represents a major setback for banditry in the North West. As a key leader with the capacity for high-profile attacks, his absence is likely to undermine the operational effectiveness of bandit groups. Moreover, as a prominent arms supplier, Sububu’s removal may limit the bandits’ access to weapons, further weakening their capacity for attacks. State forces could capitalize on this gain to launch more targeted operations.

The attack on Sububu underlines the importance of intelligence-led operations against bandit groups. State forces killed him during a brief window of vulnerability, targeting him on an open road, and there are reports that communities provided intelligence that contributed to the operation’s success. However, these efforts must be conducted in a way that minimizes the risk of reprisal attacks, which occur when bandits identify communities that share information with the authorities.

There is precedent for bandit reprisals against communities in the area. For example, in May 2022, bandits attacked communities in Zamfara, killing more than 50. The massacre was fuelled by the killing of 10 bandits by state forces two weeks earlier. The bandits suspected that these communities had tipped off the authorities.

In light of these risks of a violent fallout, it is critical for the government to prioritize the protection of communities, particularly in the aftermath of high-profile operations such as Sububu’s killing. Failing to do so could erode community trust in the state and make future intelligence-gathering efforts much more difficult.