Posted on 09 Jan 2026

The US military offensive on Christmas Day in Nigeria – described by President Donald Trump as ‘a powerful and deadly strike against ISIS Terrorist Scum’ – may ultimately achieve the opposite of its intended effect.

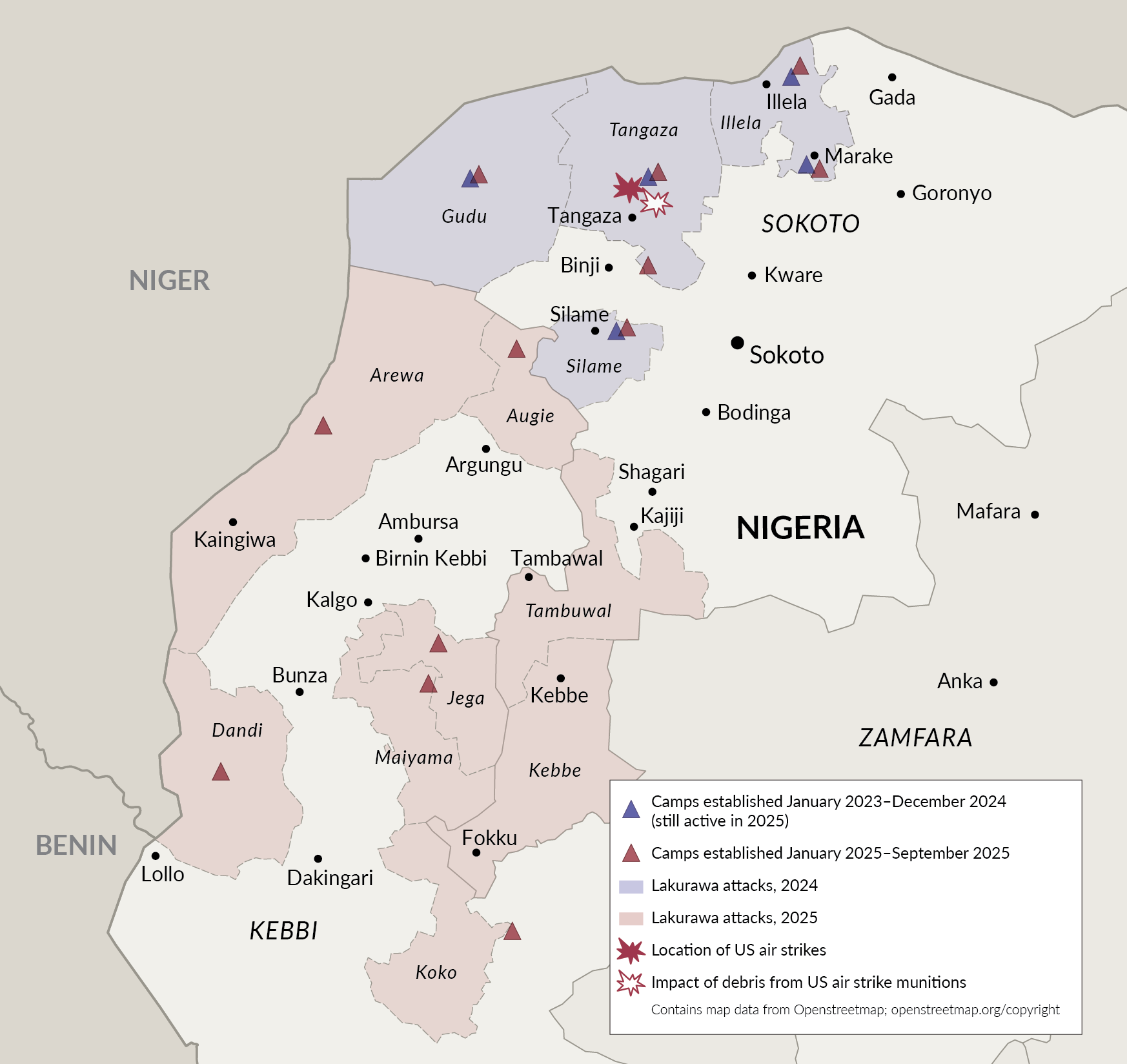

Lakurawa, a violent extremist group based in the North West region of Nigeria, was officially designated a terrorist organization by Nigerian authorities in November 2024. The December air strikes appear to have targeted the group’s camps in the Tangaza area of Sokoto State, close to Nigeria’s porous border with Niger. US and Nigerian officials claimed that the action resulted in multiple casualties, with Trump declaring: ‘Every camp got decimated.’

Nigeria has insisted that the mission was a joint operation and claims it provided the US military with intelligence. However, initial reports on the ground, including GI-TOC interviews with journalists and security experts, found no evidence of the reported casualties. At least one media outlet reported that the air strikes hit ‘empty farmland’.

Although the forested areas of Tangaza are Lakurawa strongholds, sources suggest that the group was not present at the time of the attacks. Some local accounts claim that the camps had been unoccupied for weeks; others suggest that Lakurawa members had fled to Niger or moved south to other Nigerian states. Although not independently verified, media reports indicate that 39 suspected Lakurawa members from Sokoto were arrested in Ondo State in the days following the operation.

The US narrative surrounding the operation presents an inaccurate picture of the violence in North West Nigeria, dangerously framing it as the persecution of Christians – a notion that has been promoted by various US officials, including Trump and Senator Ted Cruz, in recent months. Although military action, including air strikes, can be an effective response to high-intensity violence, deficiencies in real-time intelligence and the sectarian framing of the offensive may undermine its effectiveness by alienating local Muslim communities and reinforcing extremist narratives. Furthermore, given the history of mistrust of the US in the region, portraying Lakurawa as the target of American military aggression could inadvertently grant the group more legitimacy than it has managed to accrue on its own.

How a vigilante force became a predatory insurgent group

A growing number of armed groups spanning the criminal–terrorist spectrum are emerging in Nigeria’s North West, and the area is poised to become a meeting ground for Nigerian and Sahelian networks, forming alliances or conflicts that could reshape the region’s security landscape. Some of these groups have a history of leveraging air strikes to build local legitimacy, presenting themselves as protectors of communities against government aggression. This reduces the need for violent action in areas under their control, thus enhancing operational efficiency.

In the case of Lakurawa, the sectarian framing of the December offensive, and the group’s background, heightens the risk that they will benefit from it. The group started operating in Nigeria as a community defence force, but developed into a highly violent and exploitative outfit, financed by various illicit activities, including cattle rustling, kidnapping, extortion and the illicit oil trade. The group’s actions have alienated it from many of the communities it formerly served; however, the December air strikes could reverse this dynamic.

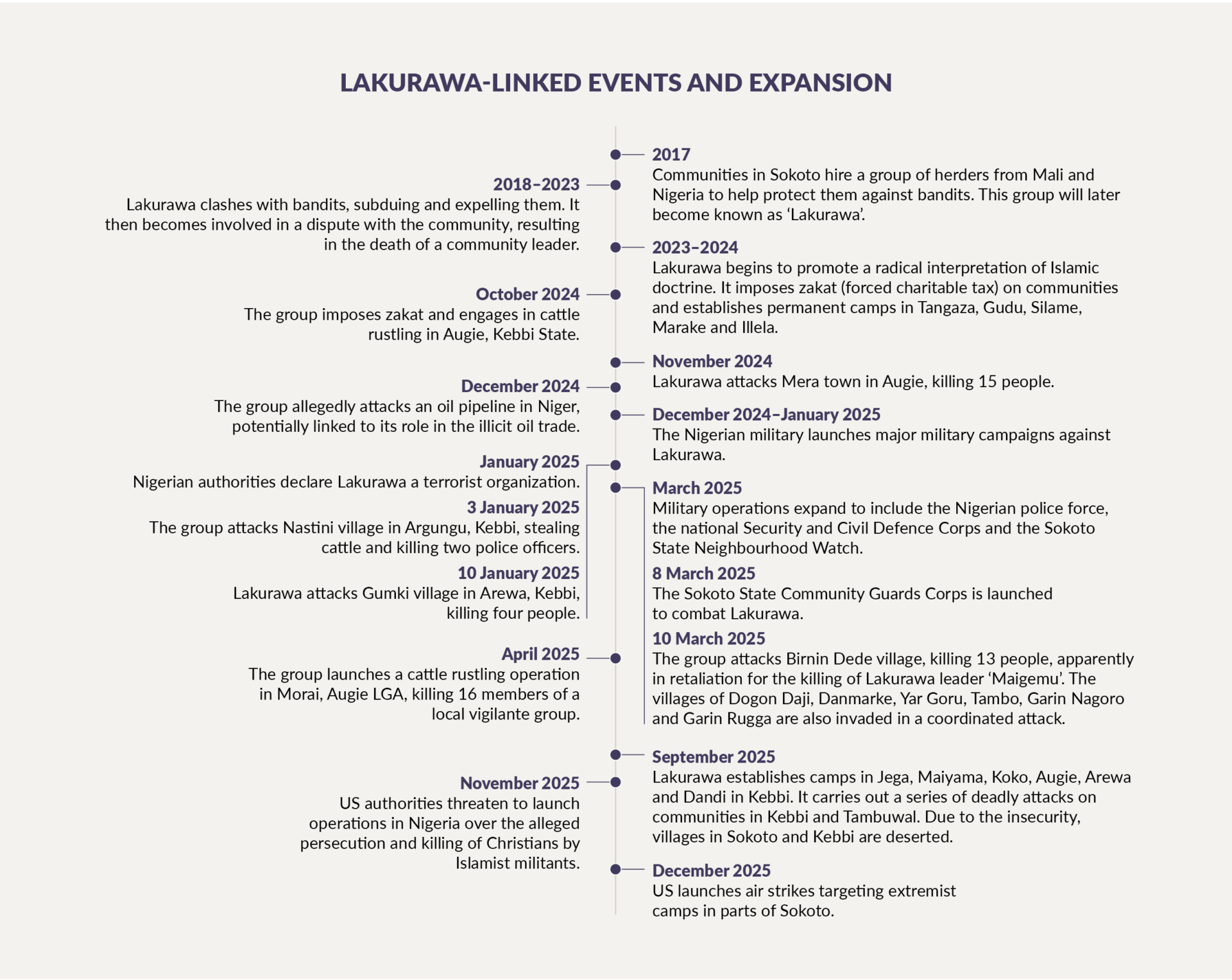

Lakurawa emerged in 2017, when communities along the Niger–Nigeria border enlisted an assemblage of herders, largely Malian and Nigerien nationals, to help combat armed bandits. The group’s name is a Hausa adaptation of the French term les recrues, meaning ‘the recruits’. While the scheme was initially successful, Lakurawa quickly became hostile to the communities it had protected, imposing protection levies, confiscating livestock and enforcing a rigid interpretation of Islam.

Between 2020 and 2022, Lakurawa became increasingly predatory, even collaborating with the bandits it had initially been tasked to oppose. In 2024, it reportedly pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, as part of that group’s expansion plans. (Notably, while some analysts posit that the group may instead be affiliated to al-Qaeda, this was not borne out by GI-TOC research.) In 2025, violence linked to Lakurawa surged, with dozens of fatalities and the widespread destruction of homes leading to large-scale displacement in Sokoto and Kebbi.

Today, Lakurawa can be described as a group that preaches ideology while engaging in criminal activity. The group’s rapid territorial expansion has given it greater access to revenue sources that were most likely not affected by the December attacks. While air strikes may destroy physical infrastructure, they will not dismantle the coercive arrangements that underpin the armed group’s influence over local communities.

In addition, the group’s reported affiliation with the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara raises the prospect of a potential nexus between extremist elements in the Sahel and Nigeria. This could result in the formation of a bridge and resourcing corridor, enhancing the resilience of these groups across West Africa. There are already reports that arms trafficking between Islamic State-affiliated groups in northern Nigeria and Mali has begun.

Measuring the fallout: Intelligence failures and narrative warfare

Beyond the legitimacy risks, the execution of the US operation in December raises serious questions about the long-term effects of air strikes against mobile insurgent groups. The intelligence used to plan the attacks appears to have been outdated. Lakurawa’s members frequently operate using motorcycles and can therefore respond rapidly to perceived threats. This makes it far more likely that they will be displaced rather than disrupted in the long term. There has been a pattern of geographic dispersion following military operations by Nigerian forces against bandits in Kaduna and Zamfara states, which has frequently resulted in an expanded scope of insecurity.

The framing of the December strikes compounds these problems. Washington has justified the operation as an intervention against a terrorist group to protect persecuted Christian populations, but these statements mischaracterize Nigeria’s security crisis, which affects both Muslim and Christian communities. This narrative ignores the fact that Nigeria’s conflict drivers are predominantly rooted in criminality rather than purely sectarian ideologies, and threatens to deepen divisions and exacerbate communal fault lines in an already fragile social landscape.

As a result, the quality of intelligence available to the Nigerian government, and its US allies, may be set to deteriorate. As sectarian narratives are often weaponized by extremist groups to reinforce propaganda that portrays foreign actors as hostile to Islam, the attacks risk fostering sympathy or passive support for armed groups among populations whose trust is essential for state counterinsurgency efforts. Portraying political or criminal violence as a religious struggle can alienate the Muslim communities whose cooperation is vital for intelligence gathering and community-based security initiatives.

Mission accomplished?

Trump described the December air strikes in North West Nigeria as a ‘Christmas present’ for terrorists. He was being ironic, but his pronouncement may turn out to be true. If the outcome was indeed a lack of casualties, increased legitimacy for Lakurawa and a deterioration in the flow of intelligence from local communities to national and international agencies, then the operation may well have handed Lakurawa and other armed groups in the region a gift, with far-reaching consequences for the conflict landscape in West Africa.