Posted on 10 Jul 2020

A new report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows, pulls back the curtain on one of the more notorious players in global illicit financial flows (IFFs). Although Dubai is just one of many players enabling transnational IFFs, its significant role as a global financial hub and as a leader in the gold trade pose a particularly complex challenge.

The CEIP report comes on the back of the recent Financial Action Task Force (FATF) assessment of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) anti-money-laundering and counterterrorist financing system, which found that the UAE is not addressing money laundering effectively and raises concerns about the emirate’s ability to combat financing of terrorism. According to the FATF risk assessment, the UAE’s vulnerabilities to money laundering encompass a collision of risks, including the large size and openness of its financial sector and the country’s geographic proximity to countries destabilized by conflict or terrorism, or which are subject to UN sanctions.

The precious-metal and stones sector (specifically gold, which generates tens of billions of dollars for the UAE) is identified by the FATF as a high-risk economy. The FATF reports that there are over 7 000 diamond and precious-metal dealers in the emirate state and that the sector is heavily exposed to cash transactions. Most of the activities related to this sector are located in Dubai, where significant volumes of goods pass through the Jebel Ali Free Zone.

The FATF findings do not come as a surprise and reflect the assertions made in the CEIP report under ‘Dubai’s problematic gold trade‘ by Shawn Blore and the GI-TOC’s Marcena Hunter. Dubai’s strategic location, accessibility by air and competitive marketplace have enabled the emirate to become a major international gold hub. However, lax due diligence and responsible sourcing obligations have created a free-for-all for gold smugglers. Research by the GI-TOC has found that Dubai is the dominant export destination for illicit gold flows from across Africa. In 2016, the UAE reported gold imports from Africa topping US$16 billion. That same year, the FATF noted that the UAE ranked third globally in terms of gold exports, with a total value of US$25.4 billion, or 7.8% of total world exports.

Recognizing both the immense scale of the gold flows and the regulatory weaknesses inherent in the UAE’s systems, the FATF report finds that ‘the value of seizures is likely lower than would be expected in the UAE, … While open sources report that gold is being smuggled from West Africa to the UAE, there were no seizures or confiscations in this regard.’ The CEIP report, as well as research by the GI-TOC, highlights these flows, including gold that is exported from the DRC and South Sudan via Uganda, Sierra Leone via Guinea, Ghana and Liberia, and from West Africa as a whole.

Most gold is hand-carried to Dubai by air and sold in the gold souk. Because gold dealers in the souk need only a UAE customs form to trade, which does not require information about the gold’s origin, they are able to accept gold originating from any country, no questions asked. Gold purchases are often recorded as scrap, rather than sourced from artisanal and small-scale mining. This enables refineries that buy gold from the souk to claim that they do not source mined gold. In this way, gold is laundered into a refined product that is acceptable to the world’s most reputable gold hubs.

The Dubai Multi-Commodities Centre (DMCC) established the Dubai Good Delivery standard in 2012 and the DMCC Rules for Risk Based Due Diligence in the Gold and Precious Metals Supply Chain in 2016, which brought Dubai’s standards closer in line with the core principles of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. However, the DMCC’s sourcing and due-diligence requirements are voluntary and thus easily ignored.

The weak regulation of this form of gold trafficking and laundering is reflected in the FATF assessment, which found gaps in the use of financial intelligence and supervision of the gold sector. While the UAE has a strong financial intelligence framework, the FATF found authorities under-utilize customs data. Financial intelligence on the cross-border movement of gold (as well as other precious minerals and cash) is used insufficiently in light of the UAE’s risk profile, while statistics show that authorities are not adequately seeking information from other stakeholders in high-risk sectors, thereby missing valuable data. Also, noting the significant flows of gold to Dubai, it is alarming that the financial intelligence unit received only two suspicious transaction reports between 2013 and 2018.

The FATF assessment also identifies significant risk of trade-based money laundering (TBML). TBML is ‘the process of disguising the proceeds of crime and moving value through the use of trade transactions in an attempt to legitimise their illicit origins’. TBML in the UAE has implications for the illicit gold trade. Dubai’s free-trade zones enable gold smugglers to convert profits into commodities, which can then be imported into Africa as payment for the gold or to disguise the illicit profits. For example, in Kampala, Uganda (a major recipient of gold smuggled from neighbouring countries before it is exported to Dubai), gold deals are often done with payments in the form of commodities.

There is a significant crossover between TBML and free-trade zones. As reported in the CEIP publication, Dubai’s gold-oriented free-trade zones are thriving; in 2018, the DMCC welcomed 1 868 new companies to its zone. Systematic weaknesses that make free-trade zones vulnerable to money laundering include relaxed oversight, lack of transparency, and an absence of trade data and systems integration. Hence the UAE’s expansion of its free-trade zones, in an effort to position the country as a major international and regional trading hub, exposes the country to heightened risk of money laundering.

The vulnerabilities linked to money value transfer systems identified by the FATF also have implications for the illicit trade in gold. Money value transfer systems, in particular hawala, can be used to launder gold and illicit profits. Hawala is a money transfer system dating back centuries that operates across South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. In some parts of Africa, gold traders are known to pay for gold using the hawala system. In the UAE, there is a significant amount of hawala trade operating outside of the regulatory regime. Although the UAE is a known hawala hub, the FATF reports that, as of December 2018, there were only seven registered hawaladars, and the UAE was not able to quantify the exact amount of hawaladar activity given recent changes to the regulatory regime.

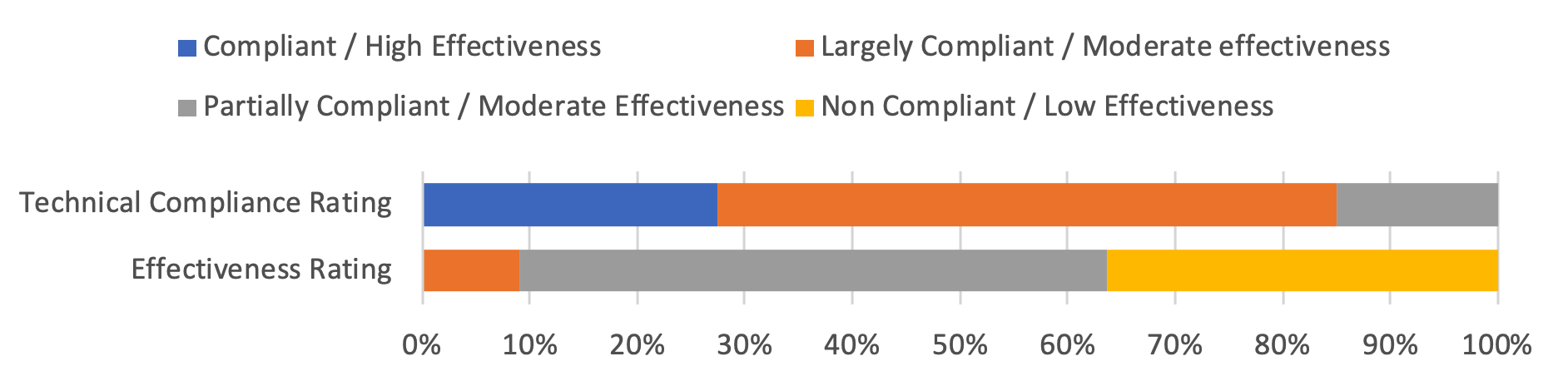

While there are significant concerns raised by both the CEIP and FATF reports, there are signs of hope and recommendations on action the UAE can take to combat gold trafficking and money laundering more effectively. The UAE has taken steps to strengthen its legal framework to combat money laundering and to increase transparency in gold supply chains. What remains to be seen is whether action goes beyond talk and legal frameworks on paper. The discrepancy between the country’s technical compliance and effectiveness highlights the need for substantive, comprehensive action that makes use of the resources and frameworks that are already in place.

As of April 2020, the UAE has been placed under a year-long observation by the FATF. For many gold watchers, it is hoped that the FATF assessment and this period of observation will be the catalyst for change that many have been calling for and an end to business as usual in Dubai’s gold markets.