Posted on 25 Aug 2025

Prison reform has become increasingly urgent, at a time when the link between the criminal justice system’s shortcomings and organized crime has become more apparent. With approximately 11.5 million people incarcerated globally – more than at any point in human history – the implications extend far beyond the prison walls.

While only a fraction of inmates are involved in organized crime, their influence is often disproportionately large. The UK estimates that 10.6% of its prison population participates in serious or organized crime, with one in five organized crime groups operating within prisons. In contrast, the US Federal Bureau of Prisons reports that just 0.2% of inmates are involved in what is termed ‘continuing criminal enterprise’, suggesting inconsistency in how this phenomenon is measured.

This discrepancy stems partly from how different systems classify criminal affiliations. Often organized crime affiliation is grouped under ‘gang membership’, a broader category that includes various kinds of gangs and terrorist groups. Moreover, most facilities only document those gang members who pose significant threats, leading to underestimation of the true prevalence of organized crime in prisons.

Systemic vulnerabilities enabling criminal networks

Several interconnected factors create prison environments in which organized crime flourishes. Chief among these is overcrowding, which affects 60% of countries globally, with some facilities running at 150% capacity. States that fail to provide prisoners with adequate space in their prisons may risk negatively impacting prisoners’ mental health and lowering their chances of successful rehabilitation.

This chronic overcrowding is not limited to developing nations, however, but is also part of a wider European trend – even Finland, known for its efficient judicial system, now faces this challenge. Within Europe, Romania exemplifies this crisis, ranking second only to Cyprus in prison overcrowding rates. Despite recent improvements following European Court of Human Rights interventions, and an increase in the country’s score for the resilience indicator ‘judicial system and detention’ under the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index, the country’s approach of constructing new facilities is only a temporary solution, and addresses symptoms rather than root causes.

Undertrained staff and understaffed facilities, security vulnerabilities and corruption compound these issues, and have led to multiple prison escapes – such as the Coimbra mass jailbreak attempt in Portugal in 2024. When political instability weakens judicial systems, criminal groups continue to hold decisive control even behind bars, creating prison environments that mirror the violence and dysfunction of broader society.

An additional challenge is that some of the most notorious criminal organizations – such as Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua and Brazil’s Primeiro Comando da Capital – originated in prisons, giving them particular leverage within these institutions. For many groups, detention also serves as both a recruitment ground and a badge of credibility, with criminal records enhancing an individual’s reputation within criminal hierarchies.

Why building more prisons fails

While prison overcrowding is a real problem, building additional prison facilities is a superficial fix that ignores underlying issues. This is evident when we look at the experience of Türkiye: despite building more than 130 prisons since 2016, the country’s Index score for ‘judicial system and detention’ – a measure of the power of a state’s judiciary to enforce judgements in organized crime-related cases – has stagnated since 2021 at 2.0 out of 10.

Prison construction fails because incarceration itself is often counterproductive. When imposed from a punitive rather than rehabilitative perspective, imprisonment can in fact increase recidivism rates. Factors contributing to this include a lack of a support systems, exposure to violence and the learning of new criminal behaviours from other inmates. Additionally, the social stigma following release creates barriers to employment and reintegration for former convicts, making return to life in prison more likely.

New facilities should indeed be built, but mostly with the explicit purpose of replacing older, derelict prison buildings rather than promoting the expansion of the prison network.

Evidence-based solutions

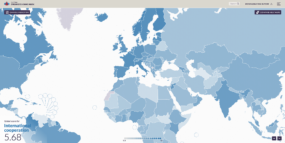

A poorly resourced judiciary or one that is under pressure from the government leads to slow and inefficient justice, which in return translates into lengthy detentions and trial delays. Countries with strong resilience to organized crime share an important characteristic: effective judicial systems combined with well-managed detention facilities. This is supported by data from the 2023 Index, which revealed a strong positive correlation (+0.90) between resilience to organized crime and strong judicial and detention systems, indicating that successful crime prevention requires addressing both elements simultaneously.

Countries that are effective in monitoring and reducing the spread of organized crime in prisons also scored highly in terms of judicial system and detention. A good example of this integrated approach is the UK’s Serious and Organized Crime Strategy, which specifically accounts for criminal groups operating behind bars and deploys a series of disruption and risk management strategies. Similarly, Germany and the Netherlands apply a ‘principle of normalization’, ensuring that life in prison mirrors life on the outside as closely as possible, to instill or preserve a sense of community and thus facilitate eventual reintegration.

Germany’s success in this regard is measurable – with an incarceration rate of just 68.9 per 100 000, compared to Türkiye’s rate of 408.4 per 100 000. Germany also ranks sixth globally under the Index’s ‘judicial system and detention’, having improved its score by 0.5 points since 2021.

Transformative reform strategies

A better evidence base on the prison–organized crime nexus is critical to better understanding and mitigating the spread of organized crime in prisons. The correlation between organized crime and judicial effectiveness demonstrates that countries cannot successfully combat criminal networks without addressing prison conditions. Overcrowded, poorly managed facilities do not just fail to rehabilitate – they may actively strengthen criminal organizations by providing recruitment opportunities and operational bases.

A truly effective prison reform strategy requires a combination of measures that address a variety of systemic gaps. Important interventions include fair sentencing policies, reducing pre-trial detention periods, strengthening access to legal aid and treating imprisonment of children as a last resort. As gang affiliation may continue after release, reforms limited to prisons may fall short of yielding meaningful results. Some states even support the prison abolition movement, envisioning a society without incarceration by developing alternatives. While implementing such a bold strategy remains aspirational, rethinking incarceration is an exercise for the present.

The associative link between punitive approaches and rehabilitation should be broken, giving way to a more enlightened thinking about justice – perhaps as restorative, reintegrative and compassionate. Countries that successfully combat organized crime understand that effective prisons do more than just contain criminals – they transform them. Societies must choose whether to perpetuate cycles of crime through punitive warehousing or to seek to build safer communities through genuine rehabilitation. Strengthening judicial and detention systems through prison reform can help to reduce the impact of organized crime.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.