Posted on 05 Nov 2024

In defiance of expectations, Afghanistan’s ban on opium in 2022 appears not to have yet affected the European heroin trade, which shows a high level of stability and reportedly abundant stockpiles. Recent police operations reveal that heroin arrives hidden in trucks and cars via historical routes, such as from Central Asia across the Balkans, as well as less usual trafficking routes. For instance, in January 2024, Italian authorities arrested a Nigerian national who was trafficking heroin that reportedly originated from the Golden Triangle. This may hint towards diversified trafficking patterns, with Myanmar now being the main producer of opium globally.

As heroin trafficking flows continue to reach Europe, there is however growing evidence that synthetic opioids have entered European markets, including fentanyl and its derivatives, highly deadly nitazenes and diverted or counterfeit prescription opioids. This suggests that synthetic opioid trafficking is developing to and within Europe, but it remains small scale and mostly invisible.

Europe’s blind spot

While public health agencies, drug harm-reduction civil society groups, and treatment and counselling organizations are stepping up their efforts to pre-empt and prepare for a potential European opioid crisis, the supply control responses appear to be less prepared. There is a massive knowledge gap about the synthetic opioid supply chains into and through Europe. Our field research suggests that the attention of European drug enforcement and border security appears to be not on synthetic opioids but rather on trans-Atlantic cocaine flows into the region. This narrow focus on cocaine is in part due to the massive increase of cocaine seizures in European ports and off the Spanish and West African coasts, diverting the attention from other potentially harmful drug-market trends.

With the focus of Western European law enforcement and customs authorities almost exclusively on drug flows from the west, another, more threatening risk may enter European ports through their unshielded back entrances. The general assumption is that most fentanyl, nitazenes and their precursors in the European market originate in China, reflecting the patterns of maritime trade of other, non-opioid synthetic drugs. However, this is not supported by sufficient evidence. Opioid trafficking is small scale and involves small amounts – in 2023, European authorities seized just 3 kilograms of nitazenes. Little is known about the importing criminal networks and their modus operandi, or about trafficking patterns. The assumption that China is the main point of origin may reflect the US government’s overall concern with the Chinese supply of fentanyl rather than be based on solid evidence. According to EUROPOL and the European Union Drugs Agency, India and Russia also appear to be countries of origin for synthetic opioids in European markets.

In addition to the maritime trade pipeline, traditional mailing systems are used to deliver synthetic opioids, which are frequently procured through dark-web sites. This option carries fewer risks due to the minimal amount of opioids needed for maximum impact. Searching for a needle in a haystack is easier than finding a few grams of fentanyl in the 350 000 postal items that pass daily through the global DHL hub at Leipzig Airport. Sales and supply through the dark web also play a significant role in the European domestic market for opioids. For example, in November 2023, British law enforcement raided a clandestine laboratory and seized the ‘largest quantity of synthetic opioids’ in UK history – 150 000 nitazene-laced tablets destined for trade on the dark web.

Synthetic opioids are not only sourced from outside of Europe but may also be produced within the EU. Expertise and infrastructure for producing high levels of synthetic drug production already exist in Europe, especially in the Netherlands, Belgium and Poland, and production facilities for fentanyl have been found in France and Estonia. It is suspected that also in Latvia and the Netherlands there is a production of this substance. Given the mobility of criminal networks and the region’s open borders, a few laboratories are sufficient to supply users across Europe. Indeed, our field research indicates that synthetic opioid trafficking networks are found across northern and western Europe. Furthermore, the dual-use character of fentanyl precursors such as NPP, which is traded legally for pharmaceutical purposes, creates a risk for illegal diversion of small amounts. Globally, France is the biggest exporter of NPP (followed by India), while the UK is the second-biggest importer (after the US), according to the International Narcotics Control Board.

Organized crime dynamics

What is unclear is which organized crime groups have a stake in the emerging synthetic opioids market within Europe. Traditionally, Turkish organized crime networks play a leading role in the heroin supply chain in Europe, and Turkish groups are the leading foreign criminal traffickers in key heroin markets, such as Germany. The European heroin market is estimated at around €5 billion and, despite its ageing and stable user population, represents an attractive market for organized crime to supply opioids. According to some analysts, the recent turf wars between European Turkish criminal networks indicate a shortage of heroin, which has led to competition over remaining trafficking flows. However, the evidence (stable levels and decreased seizures of heroin) does not yet support this possible dynamic.

Nevertheless, major changes in European drug markets and organized crime may be underway. In November 2023, Italy’s Guardia di Finanza and the US Drug Enforcement Administration uncovered a trafficking network between the US and Italy that led to the seizure of 100 000 ‘doses’ of an unspecified quantity of fentanyl and the arrest of 18 suspects. According to Italian intelligence, the ‘Ndrangheta, a key player of organized crime and international drug trafficking, is currently exploring opportunities in the synthetic opioids trade. Furthermore, the documented presence of Mexican organized crime networks in the Dutch drugs business may lead to a transfer of expertise for the production of synthetic opioids, given the pivotal role of Mexican networks in producing fentanyl for the US market. A similar pattern of knowledge transfer led to the gradual establishment of a rather industrialized methamphetamine production in the Netherlands.

What’s next for Europe?

The effect of the Taliban opium ban remains to be seen, but a generalized heroin shortage in Europe appears unlikely at this stage, as other sources may compensate for any reduction from Afghanistan. For example, heroin from South East Asia and South America, both regions with a century-long history of opium poppy cultivation. (See ‘The looming threat of synthetic opioids in Europe?’ for more information).

Evidence shows that highly potent synthetic opioids have already found their way into European drug supply chains, independently of the heroin supply dynamics. For now, the European market for synthetic opioids appears to be small scale. However, supply data is not up to date and does not necessarily reflect the fast-changing and open European drug markets, in which many different organized crime groups compete. The massive knowledge gaps about the opioid trafficking and production patterns need to closed sooner rather than later, given the uncertainty about the next developments of a deadly opioid market.

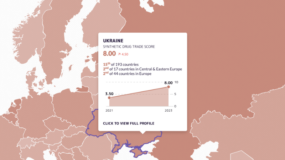

In order to contribute to field research-based understanding of these dynamics, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime has launched the European Emerging Drug Trends Monitor, which seeks to monitor wholesale and retail dynamics on European drug markets across 11 major European cities, within the EU, Ukraine and Turkey. Synthetic opioids are part of the monitoring scheme.