From Ukraine and Gaza to Haiti and Sudan, conflict is one of the major issues of our time. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which specializes in conflict data collection and analysis, 12% more conflicts were recorded in 2023 than in the previous year. One in six people are estimated to be living in active conflict zones. As with many global threats, organized crime is a common thread, and the ways in which it intersects with conflict and fragility are complex. Yet in the face of the challenges conflict presents, there is an opportunity for countries to strengthen sources of resilience to reduce the corrosive impact of criminal activities.

Organized crime can occur at any stage of a conflict: it can precede (and even cause) a conflict; it can emerge during a conflict and contribute to its duration; and, importantly, it can persist long after its resolution. Where conflict and fragility are present, social, economic and security institutions are diminished, often leaving populations to cope with shortages of goods and services. In addition, the disruption of formal economies and the displacement of civilians seeking to escape violence create economic disparities and vulnerabilities.

These gaps provide opportunities for criminal actors to exploit and for illicit activities to flourish. As the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index (henceforth, ‘the Index’) shows, many of the countries ranked as having the highest levels of criminality have been mired in conflict and instability for years, including Myanmar, Colombia, Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. From large formal conflicts to smaller, more pervasive hostilities, the majority (66%) of the countries ranked as the world’s most violent by ACLED are also in the top 50 rankings for criminality under the Index. (The Index covers the 193 UN member states, while ACLED monitors 234 countries and territories.)

The infiltration of illicit activities into fragile contexts not only exacerbates criminality, but also undermines countries’ ability to respond effectively and with meaningful and lasting impact. There is a strong negative correlation of -0.86 between the Index’s global resilience scores and the Fragile States Index. In other words, more fragile states are likely to be less resilient to organized crime.

But what does it mean to be resilient to organized crime? Understanding a country’s ability to withstand, disrupt and prevent organized crime is just as complex as understanding criminality itself. Recognizing that organized crime manifests itself differently in various contexts, including conflict settings, the Index’s resilience indicators are multi-sectoral, targeting areas of society at risk of exploitation by criminal groups through political, economic, legal and social measures.

Fundamentally, the Index’s ‘whole of society’ approach implies that the responsibility for resilience lies with state and non-state actors alike. This is crucial in light of the Index’s findings, which show that state fragility is closely linked to state-embedded actors, whose presence enables criminal markets to thrive amid corruption and limited governmental oversight. Put another way, institutions and actors that are mandated to respond to organized crime can, in some cases, hinder resilience and perpetuate criminality.

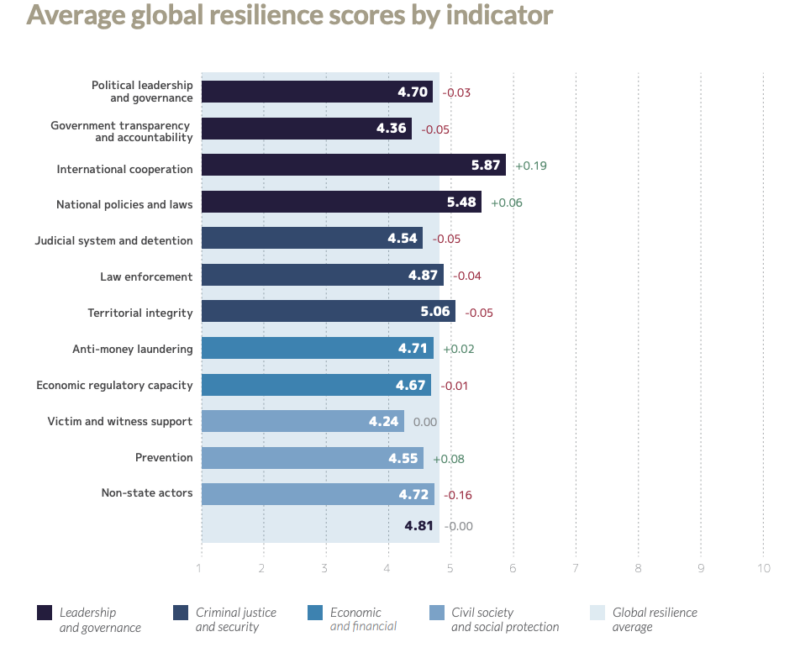

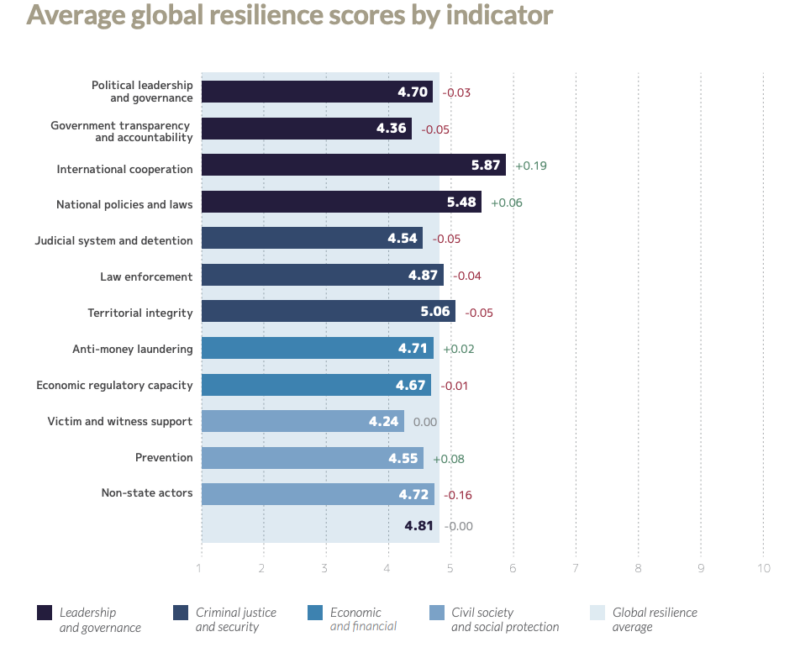

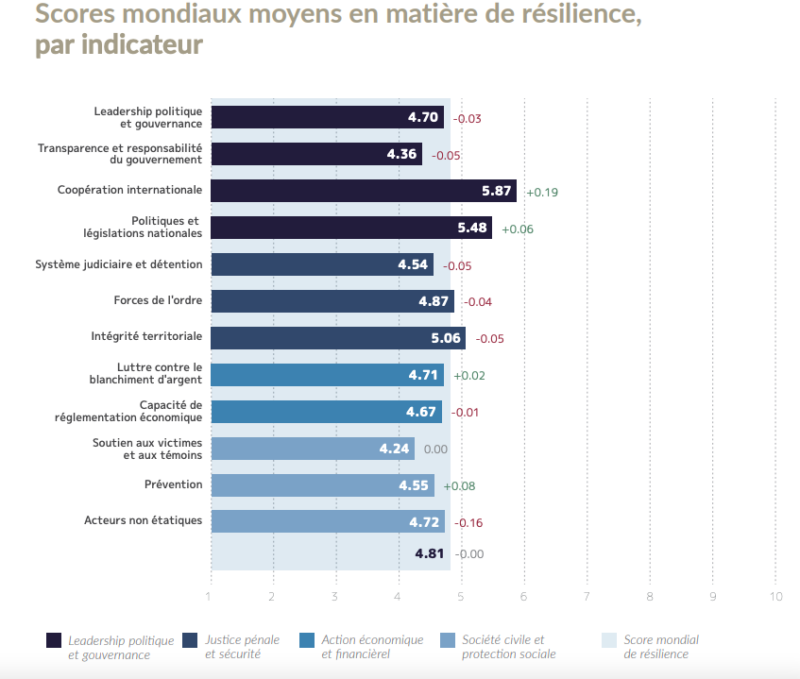

While this is certainly not true in all cases, and indeed many formal state structures have demonstrated integrity in their functions, the Index’s data shows a persistent global emphasis on institutional responses to organized crime at the expense of other areas. Governance-based resilience measures such as ‘international cooperation’ (with a global average of 5.87 out of 10) and ‘national policies and laws’ (5.48) not only received the highest scores in 2023, but also saw the largest increase since the 2021 iteration of the Index. Similarly, state-based criminal justice and security measures such as ‘territorial integrity’ and ‘law enforcement’ (ranked third and fourth, respectively) have remained consistently higher than more social-based resilience indicators.

However, a glaring deficit in the effectiveness of formal state responses to organized crime is seen in the Index’s ‘government transparency and accountability’ indicator, which was found to have the second lowest score of the 12 resilience indicators (4.36), and which saw a decline since 2021. While this data highlights the need for improvement in formal policies and strategies to counter organized crime, it should also serve as a warning against over-reliance on government-led and security-based strategies.

The 2023 Index results show a marked imbalance between securitization and non-state actor approaches, with social protection indicators scoring the lowest of all resilience groupings. For example, while the ‘non-state actors’ indicator – which takes into account the role of the media, the private sector and civil society in responding to organized crime – performed comparatively well against the overall global resilience average (4.72 out of 10), this indicator experienced the largest decline (-0.16) since 2021. Similarly, lower scores for measures such as ‘prevention’ and ‘victim and witness support’ (which scored the lowest of all resilience indicators at 4.24) would suggest that systems designed to protect those most vulnerable to the harms of organized crime are afforded little priority. ‘It is evident more needs to be done to address the relationship between organized crime and global trends, and the impact that illicit economies exert on governance and well-being,’ said Mark Shaw, director of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC).

Non-state actors can supplement government responses and provide critical checks and balances on state institutions when they fall short, particularly in contexts of conflict. For example, in the aftermath of conflict, amid weakened institutions, community initiatives are well placed to provide ex-combatants with viable alternatives to criminal activities and violence. Civil society’s proximity to communities most affected by criminality makes it well-positioned to encourage local ownership of responses to organized crime, ultimately leading to long-lasting and sustainable resilience. However, of the most violent countries listed by ACLED, half have seen a decline in their ‘non-state actors’ resilience indicator under the Index since 2021.

Recognizing the importance of locally driven resilience, the GI-TOC’s Resilience Fund has launched the fifth edition of its Resilience Fellowship, which provides a platform for cross-sectoral, global and interdisciplinary collaboration between civil society actors, human rights activists, journalists, artists, scholars, policymakers, grass-roots community leaders and others working to counter the effects of organized crime.

The theme of the 2024 Fellowship, ‘Fragility and resilience’, is aimed at civil society actors who support communities in contexts of fragility, particularly those experiencing conflict. The Fellowship will bring together a cohort of civil society individuals working in various contexts of fragility. It will provide mentorship opportunities and capacity-building workshops as Fellows collaborate on exploring fragility and community resilience through a cross-cultural lens. The 2024 Fellowship will run from July 2024 to June 2025, with an open call for applications until 25 May 2024.

As organized crime continues to drive conflict and fragility all over the world, state actors are not alone in their ability to respond. From gang violence to protracted civil wars, non-state actors in the civic space are uniquely positioned to not only contribute to peacebuilding, but take on the social, economic and political drivers that lead to criminality and conflict from the ground up.

This analysis is part of the GI-TOC’s series of articles delving into the results of the Global Organized Crime Index. The series explores the Index’s findings and their effects on policymaking, anti-organized crime measures and analyses from a thematic or regional perspective.

Reformular la resiliencia

La sociedad civil es fundamental para combatir la criminalidad en contextos de fragilidad

Desde Ucrania y Gaza hasta Haití y Sudán, los conflictos son uno de los principales desafíos de nuestro tiempo. Según el Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), especializado en la recopilación y el análisis de datos sobre conflictos, en 2023 se registraron un 12 % más de conflictos que el año anterior. Se calcula que una de cada seis personas vive en zonas de conflicto activo. Como ocurre con muchas amenazas globales, el crimen organizado es un hilo conductor, y las formas en que se entrelaza con los conflictos y la fragilidad son complejas. Ante estos retos, países de todo el mundo tienen la oportunidad de reforzar sus fuentes de resiliencia y reducir el impacto de las actividades criminales.

El crimen organizado puede aparecer en cualquier fase de un conflicto: puede precederlo (e incluso provocarlo); puede surgir durante un conflicto y contribuir a su duración; y puede persistir mucho después de su resolución. Cuando hay conflicto y fragilidad, las instituciones sociales, económicas y de seguridad se debilitan, dejando a la población con escasez de bienes y servicios. Además, la interrupción de las economías formales y el desplazamiento de civiles que tratan de escapar de la violencia crean disparidades económicas y otras vulnerabilidades.

Estas desigualdades ofrecen oportunidades para los criminales y las actividades ilícitas. Como muestra el Índice global de crimen organizado 2023 (en adelante, «el Índice»), muchos de los países clasificados con los niveles más altos de criminalidad llevan años sumidos en conflictos e inestabilidad, como Myanmar, Colombia, Afganistán y la República Democrática del Congo. Desde grandes conflictos formales hasta hostilidades más pequeñas, la mayoría (66 %) de los países catalogados como los más violentos del mundo por ACLED se encuentran también entre las primeras 50 clasificaciones de criminalidad según el Índice. (El Índice abarca los 193 Estados miembros de la ONU, mientras que ACLED monitorea 234 países y territorios).

La infiltración de actividades ilícitas en contextos frágiles no solo incrementa la criminalidad, sino que también disminuye la capacidad de los países para responder con eficacia y con un impacto significativo y duradero. Existe una fuerte correlación negativa de -0,86 entre las puntuaciones globales de resiliencia del Índice y el Índice de Estados Frágiles. En otras palabras, es probable que los Estados más frágiles sean menos resilientes al crimen organizado.

Pero ¿qué significa ser resiliente al crimen organizado? Comprender la capacidad de un país para resistir, desarticular y prevenir el crimen organizado es tan complejo como comprender la propia criminalidad. Reconociendo que el crimen organizado se manifiesta de forma diferente en diversos contextos, incluidos los entornos de conflicto, los indicadores de resiliencia del Índice son multisectoriales y se centran en áreas de la sociedad en riesgo de explotación por parte de grupos criminales a través de medidas políticas, económicas, jurídicas y sociales.

Esencialmente, el enfoque sobre el conjunto de la sociedad del Índice implica que la responsabilidad de la resiliencia recae tanto en los actores estatales como en los no estatales. Esto es fundamental en relación con las conclusiones del Índice, que muestran que la fragilidad de un Estado está estrechamente vinculada a los actores integrados en él, que permiten que los mercados criminales prosperen a través de la corrupción y una supervisión gubernamental limitada. Dicho de otro modo, las instituciones y los actores que tienen el deber de responder al crimen organizado pueden, en algunos casos, obstaculizar la resiliencia y perpetuar la criminalidad.

Aunque esto no es así en todos los casos (y muchas estructuras estatales han demostrado integridad en sus funciones) los datos del Índice muestran un énfasis global en las respuestas institucionales al crimen organizado en perjuicio de otras áreas. Las medidas de resiliencia basadas en la gobernanza, como la «cooperación internacional» (con una media global de 5,87 sobre 10) y las «políticas y leyes nacionales» (5,48), no solo recibieron las puntuaciones más altas en 2023, sino que también experimentaron el mayor incremento desde la edición 2021 del Índice. Del mismo modo, las medidas de justicia penal y seguridad gubernamental, como «integridad territorial» y «cuerpos de seguridad» (en tercer y cuarto lugar, respectivamente), se han mantenido sistemáticamente por encima de los indicadores de resiliencia de base más social.

Sin embargo, se observa un déficit en la eficacia de las respuestas estatales al crimen organizado en el indicador «transparencia gubernamental y rendición de cuentas», que tuvo la segunda puntuación más baja de los 12 indicadores de resiliencia (4,36), y que experimentó un descenso desde el 2021. Aunque estos datos ponen de manifiesto la necesidad de mejorar las políticas para combatir el crimen organizado, también deberían servir de advertencia contra la excesiva dependencia de las estrategias gubernamentales y con enfoque en la seguridad.

Los resultados del Índice 2023 muestran un marcado desequilibrio entre los enfoques de seguridad y de actores no estatales, siendo los indicadores de protección social los que obtuvieron la puntuación más baja de todas las agrupaciones de resiliencia. Por ejemplo, mientras que el indicador «actores no estatales» (que mide el papel de los medios de comunicación, el sector privado y la sociedad civil en la respuesta al crimen organizado) obtuvo unos resultados comparativamente buenos frente a la media global de resiliencia (4,72 sobre 10), este indicador experimentó el mayor descenso (-0,16) desde 2021. Del mismo modo, las puntuaciones de medidas como «prevención» y «apoyo a víctimas y testigos» (que obtuvieron la puntuación más baja de todos los indicadores de resiliencia, con un 4,24) sugerirían que los sistemas diseñados para proteger a los más vulnerables de los daños del crimen organizado reciben poca prioridad. «Evidentemente, hay que hacer más para encarar la relación entre el crimen organizado y las tendencias mundiales y la influencia que ejercen las economías ilícitas sobre la gobernanza y el bienestar», dijo Mark Shaw, director de Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (la Iniciativa global contra el crimen organizado transnacional, GI-TOC).

Los actores no estatales pueden complementar las respuestas de los Gobiernos y servir de contrapeso a las instituciones estatales cuando estas se quedan cortas, sobre todo en contextos de conflicto. Por ejemplo, tras un conflicto, en medio del debilitamiento de las instituciones, las iniciativas comunitarias están bien situadas para ofrecer a los excombatientes alternativas viables a las actividades delictivas y la violencia. La proximidad de la sociedad civil a las comunidades más afectadas por la criminalidad la sitúa en una buena posición para fomentar la apropiación local de las respuestas al crimen organizado, lo que en última instancia conduce a una resiliencia duradera y sostenible. Sin embargo, de los países más violentos incluidos en la lista de ACLED, la mitad han experimentado un descenso en su indicador de resiliencia de los «actores no estatales» en el Índice desde 2021.

Reconociendo la importancia de la resiliencia impulsada localmente, el Fondo Resiliencia de GI-TOC ha lanzado la quinta edición de su Fellowship en Resiliencia, que proporciona una plataforma para la colaboración intersectorial, global e interdisciplinar entre actores de la sociedad civil, activistas de derechos humanos, periodistas, artistas, académicos, responsables políticos, líderes comunitarios y otros que trabajan para contrarrestar los efectos del crimen organizado.

El tema del Fellowship 2024, «fragilidad y resiliencia», está dirigido a los actores de la sociedad civil que apoyan a las comunidades en contextos de fragilidad, especialmente a las que sufren conflictos. El Fellowship reunirá a un grupo de personas de la sociedad civil que trabajan en diversos contextos de fragilidad. Ofrecerá oportunidades de tutoría y talleres de capacitación mientras los Fellows colaboran en la exploración de la fragilidad y la resiliencia comunitaria a través de una perspectiva intercultural. El Fellowship 2024 se desarrollará entre julio del 2024 y junio del 2025, con una convocatoria de candidaturas abierta hasta el 25 de mayo del 2024.

Mientras el crimen organizado sigue fomentando los conflictos y la fragilidad en todo el mundo, los actores gubernamentales no están solos en su capacidad de respuesta. Desde la violencia de las pandillas hasta las guerras civiles prolongadas, los actores no estatales se encuentran en una posición única no solo para contribuir a la consolidación de la paz, sino para hacer frente en primera línea a los motores sociales, económicos y políticos que conducen a la criminalidad y los conflictos.

Este análisis forma parte de la serie de artículos de GI-TOC que profundizan en los resultados del Índice global de crimen organizado. La serie explora las conclusiones del Índice y sus efectos en la formulación de políticas, las medidas contra el crimen organizado y ofrece análisis desde una perspectiva temática o regional.

Recadrer la résilience

La société civile est essentielle pour lutter contre la criminalité dans les contextes de fragilité

De l’Ukraine à Gaza jusqu’à Haïti et le Soudan, les conflits sont l’un des principaux enjeux de notre époque. Selon le Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), spécialisé dans la collecte et l’analyse de données sur les conflits, 12 % plus de conflits ont été enregistrés en 2023 par rapport à l’année précédente. On estime qu’une personne sur six vit dans une zone de conflit actif. Comme c’est le cas pour de nombreuses menaces mondiales, la criminalité organisée est un fil conducteur, et les façons dont elle s’entrecroise avec les conflits et la fragilité sont complexes. Pourtant, face aux défis posés par les conflits, les pays ont la possibilité de renforcer les sources de résilience afin de réduire l’impact corrosif des activités criminelles.

La criminalité organisée peut intervenir à n’importe quel point d’un conflit : elle peut le précéder (et même le provoquer) ; elle peut émerger pendant un conflit et contribuer à sa durée ; et, surtout, elle peut persister longtemps après sa résolution. En cas de conflit et de fragilité, les institutions sociales, économiques et sécuritaires sont réduites et les populations doivent souvent faire face à des manques de biens et de services. En outre, la perturbation des économies formelles et le déplacement de civils cherchant à échapper à la violence créent des disparités économiques et des vulnérabilités.

Ces lacunes offrent des opportunités que les acteurs de la criminalité peuvent exploiter et qui permettent aux activités illicites de prospérer. Selon l’Indice mondial du crime organisé 2023 (ci-après, « l’Indice »), bon nombre des pays classés comme ayant les niveaux de criminalité les plus élevés sont enlisés dans les conflits et l’instabilité depuis des années, notamment le Myanmar, la Colombie, l’Afghanistan et la République démocratique du Congo. Que ce soit des conflits officiels de grande ampleur ou d’hostilités moins importantes et plus répandues, la majorité (66 %) des pays classés comme les plus violents au monde par l’ACLED figurent également dans les 50 premiers rangs en matière de criminalité selon l’Indice. (L’Indice couvre les 193 États membres des Nations unies, tandis que l’ACLED surveille 234 pays et territoires).

L’infiltration d’activités illicites dans des contextes fragiles ne fait pas qu’exacerber la criminalité, elle compromet également la capacité des pays à réagir efficacement et à avoir un impact significatif et durable. Il existe une forte corrélation négative de -0,86 entre les scores de résilience globale de l’Indice et l’Indice de fragilité des États. Autrement dit, les États les plus fragiles sont susceptibles d’être moins résistants à la criminalité organisée.

Mais que signifie résister à la criminalité organisée ? Comprendre la capacité d’un pays à résister à la criminalité organisée, à la perturber et à la prévenir est tout aussi complexe que de comprendre la criminalité elle-même. Reconnaissant que le crime organisé se manifeste différemment dans divers contextes, y compris dans les situations de conflit, les indicateurs de résilience de l’Indice sont multisectoriels et ciblent les domaines de la société qui risquent d’être exploités par des groupes criminels au moyen de mesures politiques, économiques, juridiques et sociales.

Fondamentalement, l’approche « de l’ensemble de la société » de l’Indice implique que la responsabilité de la résilience incombe à la fois à l’État et les acteurs non étatiques. Ce point est crucial à la lumière des conclusions de l’Indice, qui montrent que la fragilité des États est étroitement liée aux acteurs intégrés à l’État, dont la présence permet aux marchés criminels de prospérer dans un contexte de corruption et de contrôle gouvernemental limité. En d’autres termes, les institutions et les acteurs qui sont chargés de lutter contre la criminalité organisée peuvent, dans certains cas, entraver la résilience et perpétuer la criminalité.

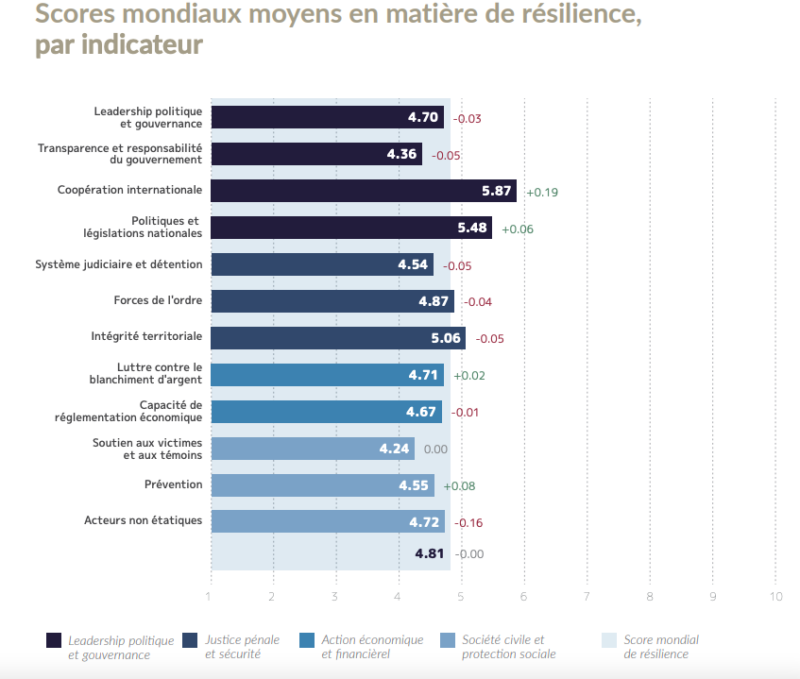

Bien que cela ne soit certainement pas vrai dans tous les cas, et qu’en effet de nombreuses institutions gouvernementales formelles aient fait preuve d’intégrité dans leurs fonctions, les données de l’Indice montrent un accent mondial persistant sur les réponses institutionnelles au crime organisé au détriment d’autres domaines. Les mesures de résilience fondées sur la gouvernance telles que la « coopération internationale » (avec une moyenne mondiale de 5,87 sur 10) et les « politiques et législations nationales » (5,48) ont non seulement reçu les notes les plus élevées en 2023, mais ont également connu la plus forte augmentation depuis l’itération 2021 de l’Indice. De même, les mesures de justice pénale et de sécurité fondées sur l’État, telles que l’« intégrité territoriale » et les « forces de l’ordre » (classées respectivement troisième et quatrième), sont restées constamment plus élevées que les indicateurs de résilience davantage fondés sur la société.

Cependant, on constate un déficit flagrant dans l’efficacité des réponses formelles de l’État à la criminalité organisée dans l’indicateur « transparence et responsabilité des gouvernements » de l’Indice, qui s’est avéré avoir l’avant-dernier score des 12 indicateurs de résilience (4,36), et qui a vu un déclin depuis 2021. Si ces données soulignent la nécessité d’améliorer les politiques et stratégies officielles de lutte contre la criminalité organisée, elles devraient également servir de mise en garde contre une dépendance excessive à l’égard des stratégies dirigées par le gouvernement et fondées sur la sécurité.

Les résultats de l’Indice 2023 révèlent un déséquilibre marqué entre les approches fondées sur la sécurisation et celles fondées sur les acteurs non étatiques, les indicateurs de protection sociale obtenant le score le plus faible de tous les groupes de résilience. Par exemple, alors que l’indicateur « acteurs non étatiques » – qui prend en compte le rôle des médias, du secteur privé et de la société civile dans la réponse au crime organisé – a obtenu des résultats comparativement bons par rapport à la moyenne globale de résilience (4,72 sur 10), cet indicateur a connu la plus forte baisse (-0,16) depuis 2021. De même, les scores plus faibles pour des mesures telles que la « prévention » et le « soutien aux victimes et aux témoins » (qui a obtenu le score le plus bas de tous les indicateurs de résilience avec 4,24) suggèrent que les systèmes conçus pour protéger les personnes les plus vulnérables aux méfaits de la criminalité organisée ne bénéficient pas d’une grande priorité. « Il est évident qu’il faut faire plus pour confronter la relation entre le crime organisé et les tendances mondiales, et l’impact que les économies illicites exercent sur la gouvernance et le bien-être des populations » , a déclaré Mark Shaw, directeur du Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (l’Initiative mondiale contre la criminalité transnationale organisée, GI-TOC).

Les acteurs non étatiques peuvent compléter les réponses des gouvernements et assurer un contrôle critique des institutions étatiques lorsqu’elles ne sont pas à la hauteur, en particulier dans les contextes de conflit. Ainsi, à la suite d’un conflit, dans un contexte d’institutions fragiles, les initiatives communautaires sont bien placées pour offrir aux anciens combattants des alternatives viables aux activités criminelles et à la violence. La proximité de la société civile avec les communautés les plus touchées par la criminalité fait qu’elle est bien placée pour encourager l’appropriation locale des réponses à la criminalité organisée, ce qui conduit en fin de compte à une résilience durable. Cependant, parmi les pays les plus violents répertoriés par l’ACLED, la moitié ont vu leur indicateur de résilience « acteurs non étatiques » baisser dans le cadre de l’Indice depuis 2021.

Reconnaissant l’importance de la résilience locale, le Fonds de résilience du GI-TOC a lancé la cinquième édition de sa bourse pour la résilience, qui offre une plateforme de collaboration intersectorielle, mondiale et interdisciplinaire entre les acteurs de la société civile, les militants des droits de l’homme, les journalistes, les artistes, les universitaires, les responsables politiques, les dirigeants des communautés locales et d’autres personnes qui travaillent pour contrer les effets de la criminalité organisée.

Le thème de la bourse 2024, « Fragilité et résilience », s’adresse aux acteurs de la société civile qui soutiennent les communautés dans des contextes de fragilité, en particulier celles qui sont confrontées à des conflits. La bourse réunira une cohorte d’individus de la société civile travaillant dans divers contextes de fragilité. Elle offrira des opportunités de mentorat et des ateliers de renforcement des capacités pendant que les boursiers collaboreront à l’exploration de la fragilité et de la résilience des communautés dans une perspective interculturelle. La bourse 2024 se déroulera de juillet 2024 à juin 2025, avec un appel à candidatures ouvert jusqu’au 25 mai 2024.

Alors que le crime organisé continue d’alimenter les conflits et la fragilité dans le monde entier, les acteurs étatiques ne sont pas les seuls à pouvoir y répondre. De la violence des gangs aux guerres civiles prolongées, les acteurs non étatiques de l’espace civique sont particulièrement bien placés pour non seulement contribuer à la consolidation de la paix, mais aussi s’attaquer aux moteurs sociaux, économiques et politiques qui conduisent à la criminalité et aux conflits à partir de la base.

Cette analyse fait partie de la série d’articles du GI-TOC consacrés aux résultats de l’Indice mondial du crime organisé. La série explore les résultats de l’Indice et leurs effets sur l’élaboration des politiques, les mesures de lutte contre la criminalité organisée et les analyses d’un point de vue thématique ou régional.