Posted on 13 May 2021

The relentless pursuit of deploying militarized raids by the police in Rio’s favelas has resulted in yet another massacre. Like previous operations, it is unlikely to have any impact on the city’s drug trafficking networks.

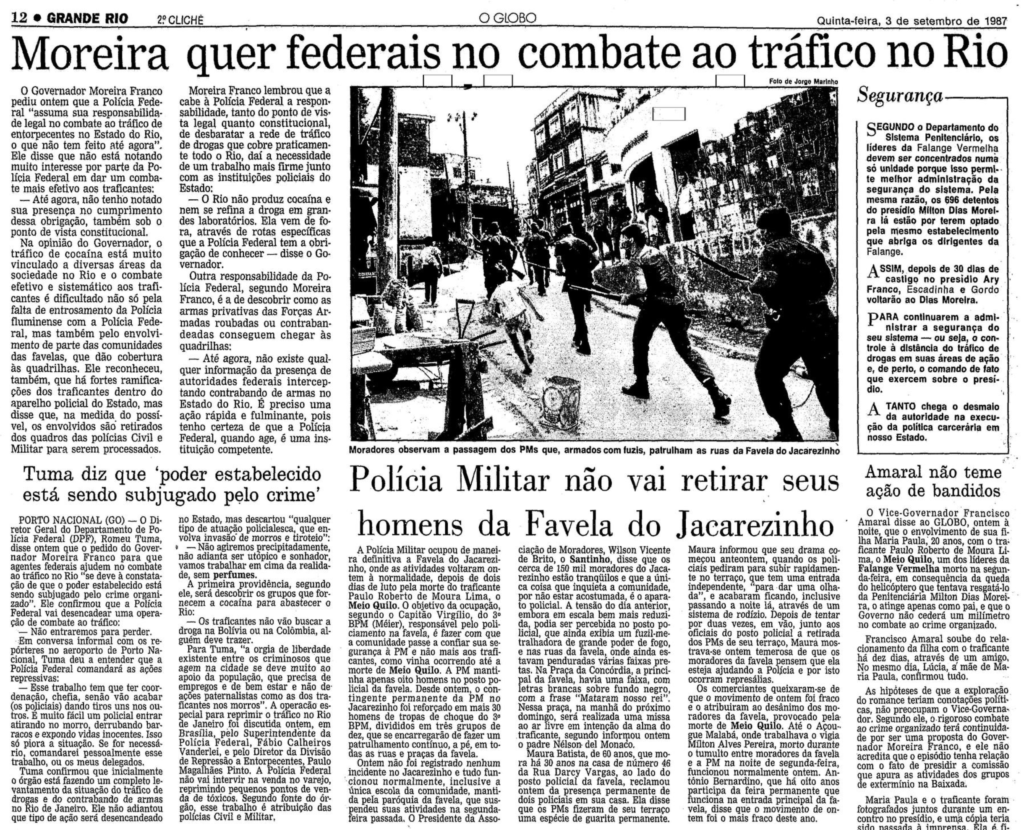

It’s September 1987. A photo in a Brazilian newspaper, O Globo, shows police officers armed with rifles storming a Rio de Janeiro favela as bystanders look on warily and a child runs excitedly alongside the men. The story headline reads: ‘Military Police will not withdraw its men from Jacarezinho favela’. In an article on the same page, the head of Brazil’s Federal Police is quoted saying that the authorities are being ‘subjugated by organized crime’.

On 6 May 2021, in an eerily familiar retake of that bloody event, 28 people were killed during another lethal police intervention in Jacarezinho, involving 200 members of Rio’s Civil Police. This was the deadliest police operation in Rio’s history. A team from the Public Defenders’ Human Rights Office, an institution tasked with offering legal council and defending human rights, said a family in Jacarezinho had witnessesd a man being killed in their eight-year-old daughter’s bedroom; the bed was covered in blood, the child ‘traumatized’. The human rights official said executions ‘probably took place’ in the operation.

The stated aim of the latest operation was to dismantle a criminal network that recruits minors and is responsible for other crimes, including hijacking a train from the local commuter railway system. The governor of Rio de Janeiro, Claudio Castro, issued a statement saying the operation was the result of a ‘detailed intelligence work and investigation that lasted ten months’. One local activist responded to this comment on Twitter to the effect that the ‘state’s intelligence in the favela is to kill’. Adding to the community’s outrage and dismay is the irony that Jacarezinho is adjacent to an area that is home to the headquarters of several police departments, including police intelligence coordination.

Plus ça change

This latest police operation is the product of a failed security policy that has been the default approach deployed by law enforcement against organized crime in Rio in its decades-long war on drug-trafficking groups. Although the police response has intensified over the years and claimed thousands of lives, it is one that has consistently failed to reduce gang violence or dismantle any organized criminal groups.

The Comando Vermelho (Red Command), the largest drug-trafficking organization in Rio, was active at the time of the 1987 reported event. The fact that the criminal group has been able to not only retain its power but increase it, should be sufficient evidence for local authorities in Rio and at a federal level in Brazil of how ineffectual their response tactics have been. They have received warnings by civil society groups and experts, who have repeatedly condemned such raids, which usually involve officers armed with rifles and armoured vehicles.

Not only have authorities stubbornly persisted with this failed iron-fist approach to criminal governance, but the wave of right-wing populism that gained strength in Brazil with the 2018 elections that ushered in Bolsonaro as president, resulted in attempts to give the police a free pass to use firepower without any overarching strategy, and with decreasing oversight. When former judge Wilson Witzel was elected governor of Rio de Janeiro state, he promised widespread deployment of snipers to shoot suspects from helicopter gunships. In January 2019, within days of being sworn in, Witzel announced the closure of the state’s security secretariat, which helped coordinate and plan security policies. In April this year, as police violence continued even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the public prosecutor’s office in Rio shut down a special division that monitored security policies and the police for potential misconduct.

The cyclical iterations of repressive responses pursued over the second half of the 2010s have borne the same hallmark – the use of rapid incursions by heavily armed security battalions, sometimes with helicopters flying low above densely inhabited slums. One activist in Rio’s Maré area said her team counted 100 bullet marks in one area following one such police operation in June 2019.

Repressive policies against organized crime, especially the ample deployment of firepower, have deep roots in Rio’s politics, with its perpetual cycle of militarized repression in the city’s slums. The state has for years banked on the ever-present appeal of being able to unleash its deadliest tool – armed force – as a quick fix solution to what are profoundly complex socio-economic problems. Back in 1987, local communities craved a swift and decisive response to organized crime, voting into power governor Moreira Franco with his promise to ‘end violence and drug trafficking within six months’. During Franco’s administration, however, the rate of homicides soared to 56 per 100 000 inhabitants in 1990 – a record at the time. According to research conducted by Silvia Ramos, coordinator of the Centre for Security and Citizenship Studies in Rio, it was also during the Franco administration that ‘the arms race between drug trafficking and police intensified like never before’ in Rio’s favelas.

As the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime showed in a 2019 report on gangs’ territorial authority in Rio, a number of policymakers have attempted to break this cycle of deadly police raids in slums. Foremost among these efforts, and the only one to gain sufficient political traction and financial support to be scaled up to emcompass several large favelas, was the Pacifying Police Units programme. The idea behind the ‘pacification’ strategy was to move away from armed raids and to introduce instead a permanent community policing presence, coupled with an ambitious socio-economic development drive. The programme reaped impressive results in its initial five or so years in terms of homicide reduction and levels of popular approval. But one of the main causes of its ultimate downfall was a failure to take socio-economic development seriously. The state was not able to muster sufficient resources or political will to introduce better infrastructure, transport or other public services in the deprived favelas.

It is more than three decades since that 1987 incursion, and thousands have since died. The recurring pattern of ultra-violent state-sanctioned operations in Rio’s slums defies any logic, especially security logic: thirty years on, Jacarezinho is still an impoverished and crime-ridden favela.

The stated objective of disrupting child gang recruitment will not be achieved by such operations, which have probably merely had the effect of traumatizing a whole generation of children while doing nothing to curtail them being lured by the gangs. The longer it takes for Brazilian authorities to ambitiously pivot to a new policy that integrates better governance and socio-economic development in Rio’s slums, the harder the job will be, and the more blood that will be spilt.